Through the rainy streets of New York, we see a Chinese food delivery man bike his way through the hectic Manhattan traffic. The camerawork is wild and shaky, as if the audience is riding along with our frail protagonist. As he goes through his day making delivery stops, the line between fiction and reality blurs — turning “Take Out” into a documentary about the inhabitants of New York.

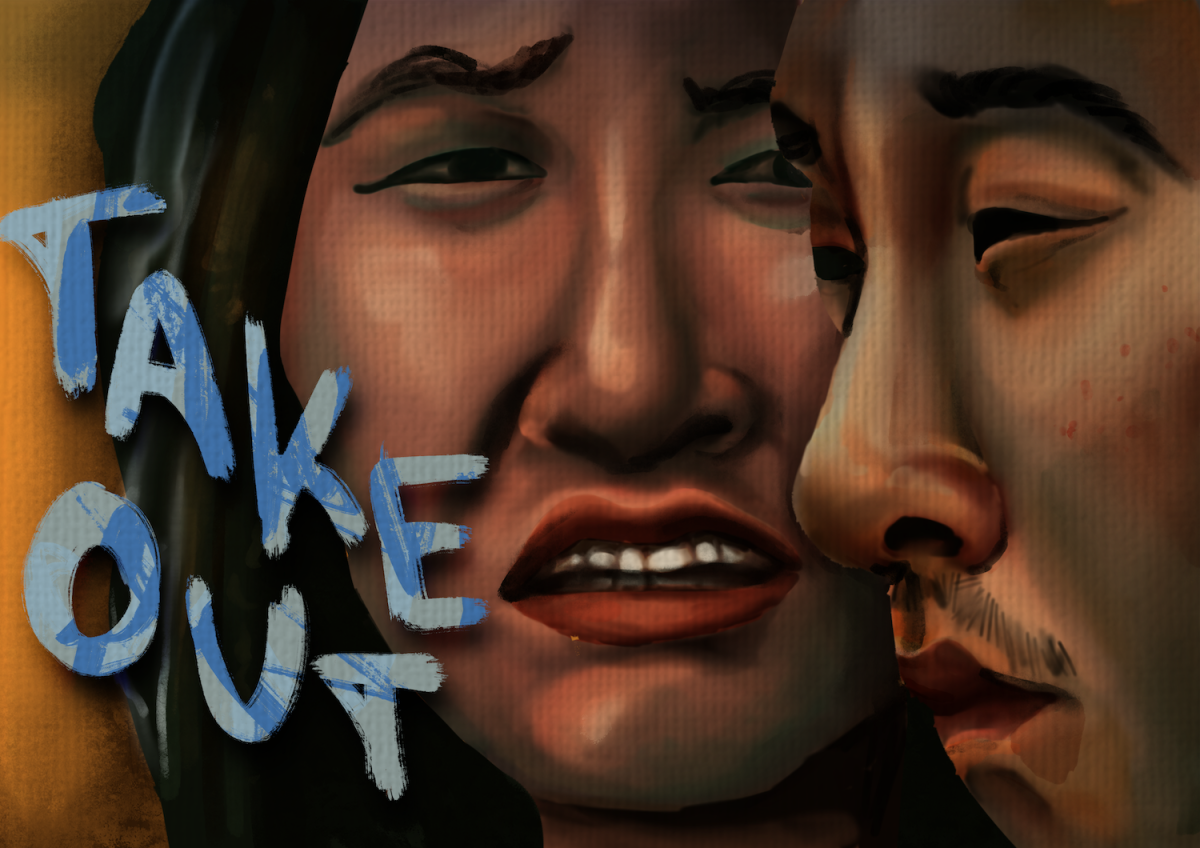

Tisch alum Sean Baker made history with his whopping four Oscar wins last month for “Anora.” But before he became a household name and a powerful advocate for independent filmmaking, Baker first gained recognition with his film “Take Out.” Co-directed with Taiwanese American filmmaker Shih-Ching Tsou, Baker’s second feature film follows an undocumented immigrant Chinese food delivery man named Ming Ding (Charles Jang) who is struggling to gather up a payment owed to his loan sharks. With a dream of building a better future with his wife and child back in China, Ming is forced to double his daily income by making as many deliveries as possible. Through his various runs, “Take Out” introduces the greasy ecosystem of New York City in its most naked moments.

Throughout his 30-year-long career, Baker has shed light onto socially marginalized groups. “Take Out” does not flinch away from showing the undercurrents of racism and xenophobia in New York nor immigrants’ continued struggle for the American Dream. Racial slurs are casually spitted out, one immigrant to another. The city is damp with the feeling of loneliness — no words of welcome or thanks are given to the delivery man riding through the rain. But “Take Out” is by no means a bleak film. While boldly presenting the harsh reality of the protagonists, Baker never forgets to look at them with a compassionate lens. Despite the unwelcoming city, Baker emphasizes that solidarity and kindness between its inhabitants are still surviving.

“Take Out” is Baker at his most New York indie. Scenes are constantly interrupted by the cacophony of New York City. The shot composition is as cramped as the spaces the crew was forced to shoot in. It is clear that Baker and Tsou had to “steal shots” in places they could not get a filming permit — including a cameo from none other than our own Rubin Hall. The camera team dangerously races along with Ming, dodging cars and buses on the roads of Manhattan. But Baker manages to create a sense of reality despite all these adverse filmmaking conditions — a rawness that carries through in his later films such as “The Florida Project” and “Anora.”

“Take Out” is a precursor to the Oscar-winning film “Anora.” It contains the sense of authenticity and frankness in Baker’s films at its most New York indie form. It is a film crucial for understanding Baker and his worldview, where we see glimpses of what we love so much about his later films — a truthful and unflinching glimpse into life.

Contact Tony Jaeyeong Jeong at [email protected].