“But take heed to yourselves, lest your hearts be weighed down with carousing, drunkenness, and cares of this life, and that Day come on you unexpectedly. For it will come as a snare on all those who dwell on the face of the whole earth.”

— Luke 21:34-35

The three remaining horsemen were left standing around, wondering what to do next, when for the third time that day, Pestilence was startled by cannon fire.

“I don’t feel lonely,” War declared. “How could I when I’m constantly surrounded by people, warriors and weapons. You don’t think ‘gosh, poor me’ when you’ve been chained to a rock and are slicing through trolls, you don’t think anything!” War struck the cannon with the side of his sword. The barrel glowed like molten steel. “I hope that our final ride is a never-ending charge because I do not want to be stuck in the dust bowl afterward.”

War sheathed his blade. He kissed their hands in an unexpected display of chivalry. “Think I’ll find a submarine.” He bowed out and ran down the hill, leaving pitter-patters of flames.

“I don’t trust the idea of him under da’ sea,” Pestilence lamented, making Famine laugh.

“I like the bald,” Famine complimented. “It works better than the dung beetles tangled up in your hair.” Pestilence remembered the scarabs fondly but was happy to hear these good words from Famine. They watched the sunset over the harbor.

“So are you off then?” Pestilence asked. “Egypt, right?”

Famine put her hands on her hips. “I’ll wander.”

“How long were you in Baltimore for?” he asked Famine.

“For the day, but I didn’t anticipate that whole deal.” She pointed at the circle of dead grass and the rotting tree.

“Whoever shows up here next is going to be awfully confused.”

“Definitely. They’ll probably blame it on pesticides.”

“A melted cannon?”

“Strong pesticides.”

Pestilence snorted. Famine still hadn’t left. “You mind if I join you as you wander out of Baltimore?” Famine said nothing but walked down the path of flaming footprints.

“Why, do you want to tag along?”

“Today isn’t over. We can ‘wander’ for a little longer.”

“Why do you think I’d want that?”

“You said you weren’t mad at me.”

“After thousands of years. Now, I’m just disappointed.”

Pestilence whistled poorly. “But that’s 10 times worse! Disappointed in me …” Famine did not find that nearly as funny as Pestilence did.

“I get why you left me, but it still hurt me. I forgive you, but I don’t have to,” Famine groaned. “I’m conflicted.”

“I left you. I can’t change that.” Pestilence tapped her right shoulder. “I know somewhere else we could go. Most places are closed by now, but I can get into somewhere without breaking windows. Walters Art Museum, and it’s got some Egyptian tchotchkes.”

“I wasn’t going to Egypt for sightseeing.” Famine crossed her arms and stared off down St. Paul Street. “It’s not far?” Pestilence pointed towards the end of the inner harbor, then started walking. Famine followed his lead.

Street lights reflected off Pestilience’s bald head. “What really happened to your crown?” Famine asked.

“Honestly, I thought you would have it. Reckon I forgot it on my way out.” He pointed at Famine’s boney hands. “Where are your scales?”

“Where I keep everything.” Famine patted her stomach.

They continued with their plan to break into an art museum. Famine’s nails, like her teeth, were versatile, so while Pestilence clung to her back she reluctantly carried him up the side of the museum, digging her claws into the stone.

The Walters was a massive greystone building with iron bars covering the windows. The building and its contents used to belong to the titular Baltimore aristocrat William Walters who, upon his death, entrusted his collection to be converted into a public museum.

“Do you have a paperclip?” Pestilence asked. Famine plucked one from her back molars. He picked the lock.

Pestilence fell in front of a monolithic black statue of a female goddess, and Famine fell on him. Getting up, she pulled her heel out of Pestilence’s back.

“Show me the mummy.”

Wrapped in bandages and decay, Famine had a hard time identifying who was resting under the painted shell. She put her nose against the glass and sniffed, sticking to the barrier. “She’s familiar, but I can’t be sure. I might have known her years and years ago.”

“They don’t last too long.”

Famine broke the seal on her nose. “Yeah, but they do add an engagement element we are severely lacking.” She was entranced by the details on the animal-headed jars. “I loved the Nile’s style, pity it faded away.”

“It pops up here and there. Want to see the Walters mascot?”

“Mascot?” Famine replied. Pestilence brought her to a dark spiral staircase left over from the original architecture. It was reminiscent of a dungeon that Pestilence had been trapped in 170 years ago.

Famine grabbed his shoulder and pointed at a sign in the stairwell. “I want to see medieval art!” Pestilence was squirming. “Come on, we’re doing something I want.”

“I thought you wanted to see the mascot.”

“I can want more than one thing. Don’t make me pull you by the ear.”

Pestilence rubbed his ear still sore from being yanked through the exit. “I always hated the medieval.”

“You were always like this! Meh, I want to see the unicorn. Meh, I don’t want to see the regenerating pig. Meh, I don’t want to pick the magic effing apple. You’re so picky,” Famine hissed.

The gallery walls were lined with golden iconography of Saints. Famine appreciated the gleam as it melded well with her materialistic nature; several gold chalices laid in the belly of the beast.

Pestilence had seen enough gold paintings in his life. “I’m not picky, I have refined tastes.”

“You can’t be obsessed with how something tastes.” In the center of the room was a life-sized Jesus on the cross, carved with devilish detail into wood. “All the renderings get the nose wrong. It was much larger and flat, like a box.” Famine wildly swung her arms. She accidentally struck the side of the figure, knocking it off its axis. Wobbling dangerously, Pestilence dashed to the other side of the figure. Both Horsemen braced for the figure to crash onto the floor, desperately oo-ing and willing the figure to stay still. Then Pestilence winced and reached out to stabilize Jesus.

Crisis averted, the Horsemen darted to the next hall to avoid the security guard investigating the proximity alarm. It would be difficult to explain their presence in a closed museum. With their backs to the wall, they waited for the guard to tell off the man watching the monitors that the flickering on the camera was a malfunction. After he left, the silence between the Horsemen continued, finally broken when Pestilence burst into a cringing grin, and Famine laughed at their combined clumsiness.

“We can see the mascot now,” Famine said.

As they snuck out of the Medieval Art section, Pestilence passed a particular painting. “Into Apocalypto” by Verner Hoznorn was on display for three weeks only. War and Death, the more infamous riders, were placed center stage. Interestingly enough, for once in his existence Pestilence was painted larger than the other Horsemen, aiming his bow directly at the viewer. The eyes were disturbingly accurate.

“Good for you,” Famine said. She was painted crouching on top of her stead clutching her scales, obscured by the rest. “We were never celebrity jockeys.”

To the right of the dungeon staircase and past the food court was the museum gift shop where Waltee was for sale.

Waltee was a big cat pharaoh, his royal headdress featured a cute cartoon snake. The only stuffed animal left on the shelf was Waltee XXL. Pestilence picked him up with both hands and presented him to Famine, declaring, “here’s a whole lotta kitty.”

Famine gasped. “I love kittens.” Famine’s experiences with furry things were generally pretty brief. She dragged her fingers around the embroidered W on the belly and knew she must have it. Famine cracked her neck and opened her mouth wide, wide enough to fit a child and possibly a Waltee XXL.

Pestilence was appalled at the dislodging of her jaw. “What are you doing?” Famine tried to answer, but with her open lamprey mouth, she could only enunciate vowel sounds. “You can’t store it there. Your bile will gunk up all the fur,” he said.

Famine’s jaws snapped shut. She plucked the fuzz caught in her snaggle tooth. “Bummer. It will be a pain to carry around.”

“You could rip it open and modify it into a backpack.”

“What would I need a backpack for?” Famine flipped through a book on subversive German photography. Photos of drunks on the pier. Photos of families at the pub. Photos of lovers at the pub. Photos of lovers on the pier. “What if we transitioned into human life? We would fake our deaths and move onto the next life once our age reared its ugly head.”

“You’d need a fake name,” Pestilence reminded, indicating the rows and rows of drunkard identifications.

“What would yours be?”

Pestilence considered this. He rattled his black nails along his teeth like a piano. “Leadtooth. Ominous enough.”

“I was thinking more like Jane,” Famine said.

Pestilence felt silly but stood by his decision. He slid his hand over Famine’s, unsettling both Horsemen. “What if we hid. We could find a dark cave in the woods and stay in the darkness, festering together. Somewhere far off, a very spiritual country, like Romania, where we would sneak out of the cave at night to feed. Embrace Czernobog.”

“What happens when the horn sounds?”

“We answer, but we won’t be the cause.”

Famine slipped her hand out from under Pestilence. She rubbed her boney wrist and stepped back into Pestilence. “We couldn’t hide for long.”

“No, but we could hide for long enough. No angels. Few demons. A fair share of zealous warlocks. War would make fun of us but wouldn’t care. Death would be pissed, but he has a sweet spot for you.”

“He recognizes responsibility greater than any of us. Pissed is an understatement.”

“I recognize the risk.” Pestilence twirled Waltee’s headdress. “I think it’s worth it.”

“How sweet.” There was a rack of Mongolian throat singing CDs next to the cash register. “What made you change?”

“I’ve realized that the rewards outweigh the risks.”

“So I’m just a reward to you.”

“That’s not what I meant and you know it.”

Famine pressed a button on the player, and a man’s deep voice split the silence with a chilling ringing of a bowl. It was a surprisingly soothing melody. “Do you dance?”

“No, not really.” Famine hugged Waltee, and pressed her back against Pestilence, who put his hands around her arms.

“Good, neither do I.” Loud footsteps signaled a heavyset guard coming to investigate the throat singing coming from the gift shop. The Horsemen crawled through a vent in the ceiling and scurried back up to the roof.

By the time they stumbled back to the Beetle, it was nearly sunrise. “You decide where you’re going yet?” Pestilence asked.

Famine stared at the fading night. “What’s in that direction?”

“Virginia. I try to avoid it.”

“Can I get a ride?”

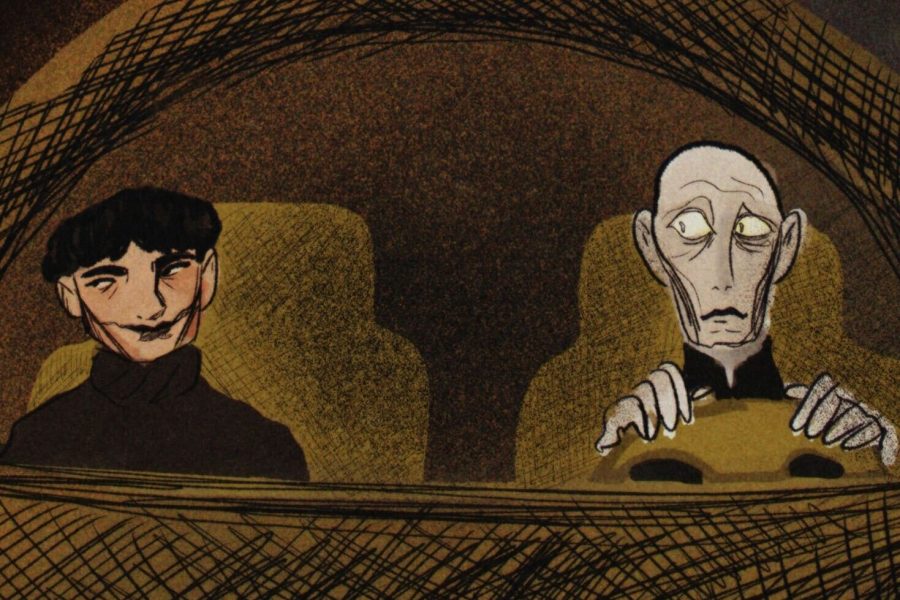

Pestilence opened the passenger side door for Famine, then got behind the wheel. Leaving the city wasn’t nearly as difficult as normal, a lack of traffic at daybreak helped. The beltway led into the highway, and once they hit congestion Pestilence veered off into country roads. Famine gave him some general directions, then, propped up Waltee as a pillow.

An old country song was playing on the radio. Over Famine’s shoulder, Pestilence saw a horse run up against the canary yellow Beetle. Where its hooves struck the ground, black mist plumed. The horse was bone-white, and it strode side by side with the car. Pestilence had never seen this horse before. He watched until it reached the end of the pasture, and the Horsemen drove off.

#

Email Leo Sheingate at [email protected].