Crossing the line: How jaywalking redefined its meaning

Under the Arch

Crossing the line: How jaywalking redefined its meaning

Originating first as a derogatory title, the phrase has since grown into a defining characteristic of the city.

Colette Yehl, Deputy Magazine Editor | October 6, 2025

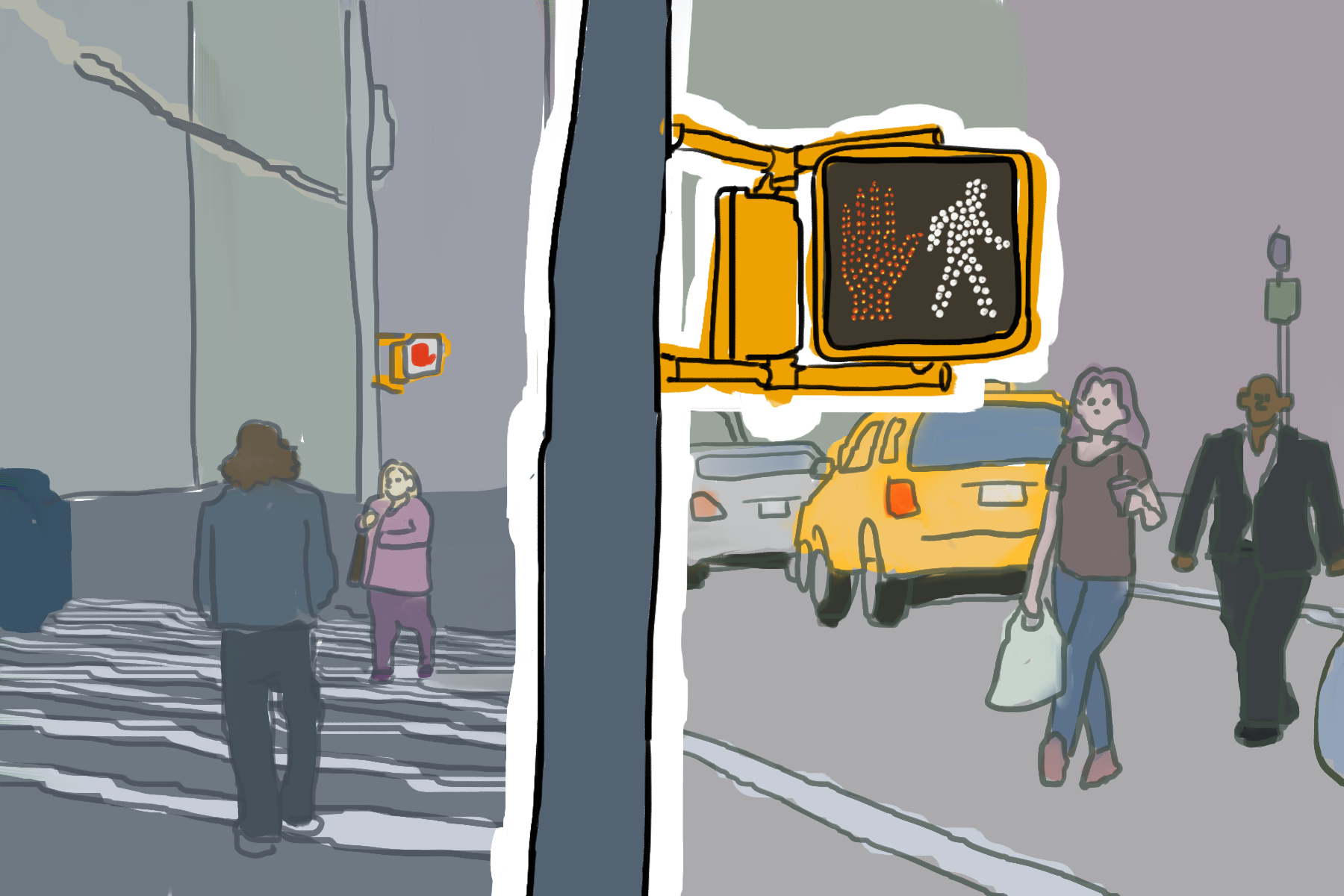

On just about every crosswalk around NYU’s campus and across the city, you’ll find pedestrians jutting across intersections, weaving through cars and dodging oncoming cyclists — long before the pedestrian signal permits them to cross.

Though they’re sometimes met with irritated honking and displeased scowls from drivers or bikers, few New Yorkers hesitate before leaving the curb. This behavior isn’t necessarily an urban faux pas. In New York City, jaywalking isn’t chaotic — it’s practically ingrained in the hectic fabric of its fast-paced culture. But this aspect of the urban identity is not often celebrated. In fact, for the greater part of the last century, the nation’s automotive industry has actively worked to discredit it.

The term “jaywalking” originated in the early 1900s to stigmatize pedestrians who interfered with automobile traffic. Since then, however, the definition has evolved first to refer to those who cross the street outside of designated crosswalks, and eventually to those who ignore the pedestrian signal at their discretion.

The phrase first appeared in a 1907 article from the Guthrie Daily Leader newspaper in Oklahoma. At that time, in the Midwest, a “jay” referred to an unsophisticated, foolish country bumpkin, similar to “hick” or “rube.” Two years before newspapers applied the term to pedestrians, The Junction City Union in Kansas used this derogatory label in an article to describe “jay drivers”: early motor vehicle operators who were unfamiliar with city driving.

But as cars began taking over roads, and streets assumed more auto-centric designs, “jaywalking” entered the average person’s vocabulary to defend motorists from reckless pedestrians, a far cry from their modern perception more so as victims than instigators. This dynamic shift coincided with jaywalking’s criminalization, which was fueled by Big Auto propaganda, serving to expand corporate ownership of city roads.

Though it’s hard to imagine today, urban streets once functioned as public spaces — think designated car-free blocks, like farmer’s markets or small downtown centers — for people to linger, children to play and vendors to do business. When cars entered the picture in the 1920s, the predictable consequences ensued. Over the first few decades of the 20th century, the amount of car-related fatalities skyrocketed. The public grew to resent automobiles, viewing them as dangerous invaders and as “frivolous playthings” — much like how yachts are perceived today. Newspapers reported on car accidents in detail, often blaming drivers and even publishing cartoons associating cars with the Grim Reaper.

In 1923, 42,000 Cincinnati residents signed a petition for a ballot initiative that would require all cars to be equipped with speed-limiting devices, restricting them to 25 mph. Though the measure failed, local auto dealers began to realize that if they didn’t initiate some kind of pushback, the future of automobiles would be in serious jeopardy.

The nation’s automotive industry, composed of car firms and lobby groups, implemented a variety of strategies to make the streets more favorable for motorists. In addition to lobbying for laws that regulate pedestrian crossing, these organizations got Boy Scouts to hand out cards explaining jaywalking. Car lobby groups also began to lead safety education in schools, and in a separate campaign, even hired clowns and actors to illegally cross the street to portray the act as ignorant and foolish.

Industry groups even managed to get the press — formerly their biggest critic — to benefit their efforts in reshaping car culture. The National Automobile Chamber of Commerce initiated a free wire service for local newspapers where reporters could submit the basic details of a traffic accident and, in return, would receive a completed, ready-to-print article. Naturally, these stories acted more as industry tools than pieces of journalism: By blaming inattentive pedestrians for car collisions, the wire service transformed jaywalking into a transgression worthy of public shame.

The jaywalking campaign’s legacy had lasting consequences on the walkability of urban spaces across the United States. Subsequent laws provided a justification for city planners to prioritize maximizing the flow and speed of vehicle traffic, disregarding pedestrians when it came to street designing. This led to wider streets, longer distances between crosswalks, neglect toward sidewalk quality and an overall lack of pedestrian-focused infrastructure.

While specific laws varied across the country, the first city to criminalize jaywalking was Los Angeles in 1925, with the auto industry submitting the initial bill. However, in 2022, California passed the Freedom to Walk Act, which decriminalized the act of jaywalking when the road is safe to cross.

Proponents of this legislation argued that it could address discriminatory enforcement against Black and Brown communities. Jaywalking laws weren’t explicitly racist but were often weaponized for biased policing, as enforcement officers often used jaywalking violations as a pretext to initiate intrusive interactions with residents of color.

For similar reasons, a few years later, New York City followed suit.

Ordering New York City’s residents and students, who are notoriously pressed for time and tolerance, not to illegally cross the street seems futile. And yet, jaywalking was previously illegal in New York for nearly 70 years, carrying a fine of up to $250.

In 1998, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani declared his anti-jaywalking campaign, raising the standard fine for committing the crime and encouraging police officers to give summonses to offenders. Ultimately, Giuliani’s measures did not have a lasting impact on the city’s jaywalking culture as it was widely ignored by residents as well as the police — who believed they had more important duties to fulfill.

Though it’s still a common practice, jaywalking hasn’t spared New Yorkers. According to the New York City Department of Transportation, within the last five years, 200 people have died while failing to use crosswalks or disobeying traffic signals, comprising almost 34% of pedestrian casualties.

But after the City Council passed the legislation in September of last year, and with Mayor Eric Adams neither signing nor vetoing it within the 30-day period, the bill legalizing jaywalking became state law in October 2024.

Opponents of the law cited pedestrian safety concerns. In their updated rules, the state government clarified that pedestrians who cross outside a crosswalk must still yield to oncoming traffic. In a civil lawsuit, pedestrians who cause an accident can still be held liable and their financial recovery in an accident claim will be based on how at fault they were.

City officials also emphasized that this law does not remove practical traffic risks and pedestrians should still maintain proper street safety awareness.

For as long as cars have been around, pedestrians have fought to maintain their grip on the city. We as NYU students assert this authority every day while making our way to class. Though the auto industry aspired to create car-dominated streets, in their own form of resistance, the ever-apathetic pedestrian continues to cross the road.

Contact Colette Yehl at [email protected].

Colette Yehl is a first-year studying media, culture, and communication. When she's not getting lost in Third North, you can find her scouring New York...

Mikaylah Du is a sophomore majoring in economics on the theory track and minoring in politics and media, culture, and communication. When she’s not tearing...