Alice Neel’s sublime portraiture

Alice Neel brings Harlem to the Guggenheim.

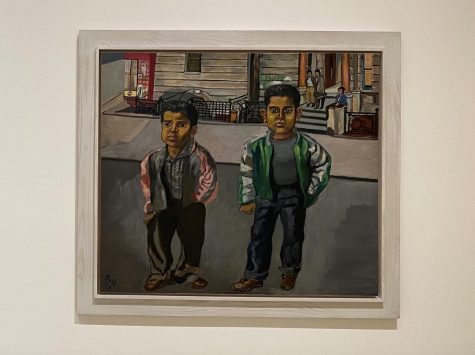

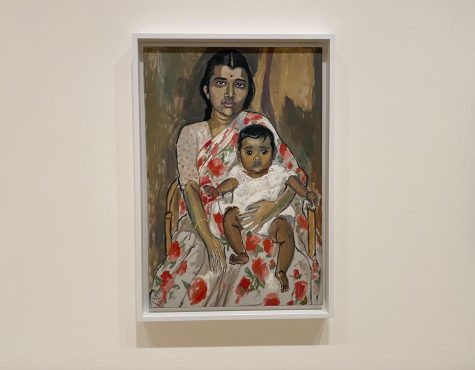

Artist Alice Neel chose unconventional subjects for her paintings. A collection of her works is currently on display at the Guggenheim in Bilbao. (Photo by Elizabeth Crawford)

October 8, 2021

“I like to paint people that have been ruined by the rat race in New York City,” Alice Neel once told Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show.

Yes, a painter on a late night talk show. Can you believe it? Bygone days. This was before broadcast networks laid siege to intellectualism, bombing the American television landscape so that only the cockroach of reality TV could emerge from the detritus. But I’m not bitter. Our generation has Kim Kardashian, a legal scholar, to widen our world and enrich our minds.

Let us return to the rat race, the ruin and the people of New York. Alice Neel was the expressionist painter of the 20th century. Her humanism never faltered, even when portraiture fell sharply out of vogue. Avoiding the postmodern trends of pop art and abstraction meant that her work would be ignored for years; but when no one was watching, Neel transformed the business of portraits into the business of framing souls.

In “Alice Neel: People Come First,” the largest European retrospective of the artist’s career, 90 drawings and paintings adorn the walls of the Guggenheim in Bilbao. The exhibition — on view until Feb. 6, 2021 — includes work from each decade of her seven-decade career. COVID-19 protocols make for a surprisingly pleasurable viewing experience — I’ve never been fond of strangers breathing on me while I contemplated art.

The first piece that seizes your attention hangs on the center gallery wall. Two figures stand with their shoulders tensed, one hand hiding in a pocket, the other forming a fist. There is calamity in their gaze. You’re convinced this is the posture of men who have turned their backs on the world — hard men, stunted by neglect. But travel down the image and your eye catches something else: pant legs collecting like puddles around their shoes. At this point you realize that the entire time you have been looking, you have not been seeing, for these are not men, but boys — boys who have hardly grown out of their jeans.

This is what Neel does: She leads your eyes to softness. Her paintings — of women, children, Black Americans, immigrants, the LGBTQIA+ community — ran in direct contrast to the images favored by contemporary popular media. She has always captured dignity in her portraits, never rarified.

The word “capture” has the masculine connotation of possession, of theft, even. But Neel takes nothing captive. Her portraits draw deep from each subject’s private well of life, only to bring to the surface what we’ve overlooked. The same is true in her depictions of femininity. By giving mothers heightened consideration — and letting breasts fall naturally, as opposed to fixing them at some comical 90-degree angle — Neel turns the male gaze inside out.

In our current age of mass media, we carry a world of images around with us everywhere, all the time. There are fewer and fewer reasons to leave the house and experience physical works of art. But do. You have to. Because Alice Neel walked out to the edge of vision and smuggled her findings through the canvas. Stand as close as you can.

Contact Elizabeth Crawford at [email protected].