My relationship with rice: Rediscovering its richness

Rice is far from boring, and it’s a staple in many cultures. Grab a bowl and let me show you how to prepare it perfectly.

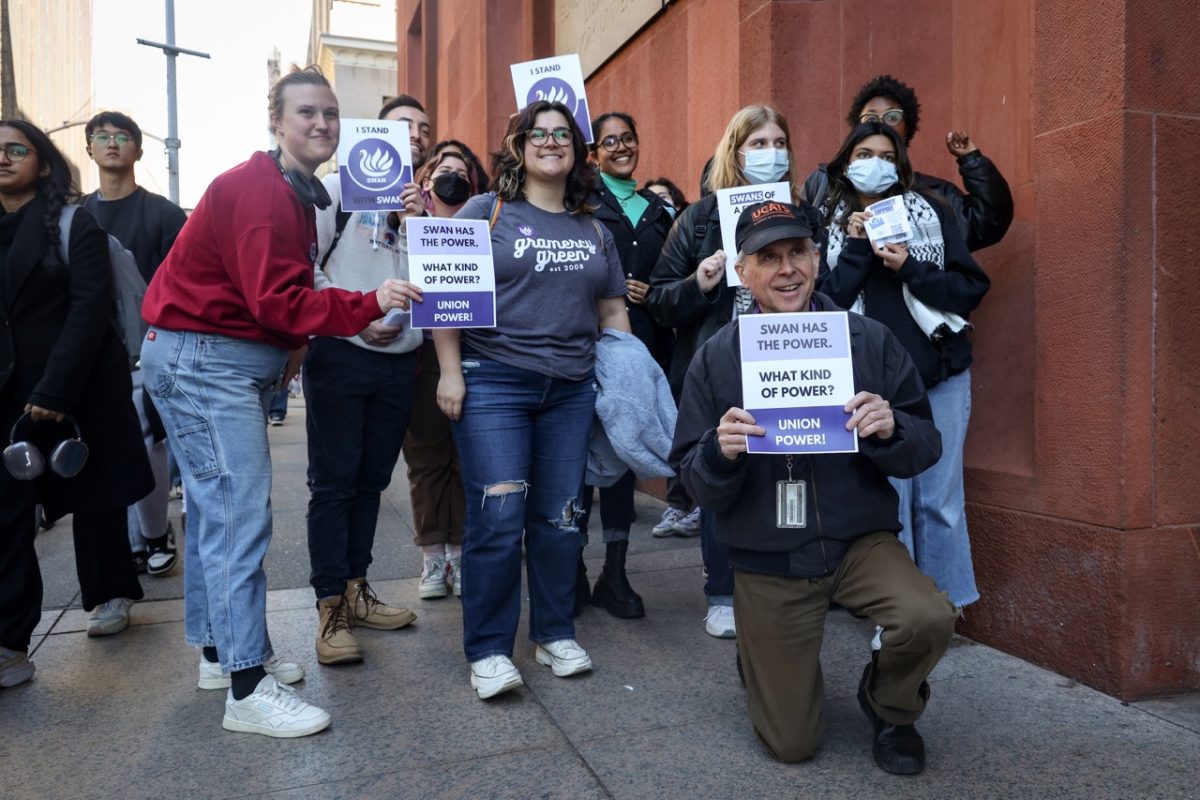

Rice is the core of many cultures’ cuisines. (Qianshan Weng for WSN)

February 20, 2023

“Bap meogeosseoyo?” When my parents call me from back home in Korea, this is the question they unfailingly ask — even if it’s not yet mealtime. One of the most frequently exchanged Korean greetings, it seems to lose its significance when translated into English: “Have you eaten bap?”

Bap literally means steamed rice, and the English translation fails to capture the importance of the culinary staple, which is ever-present in my culture and language. It’s not just a question of sustenance — I know this is their expression of affection and care, akin to asking me if I’m doing alright.

Part of the Museum of the City of New York’s “Food in New York: Bigger Than the Plate” exhibition, “Rice Stories” shows how rice plays an integral role in the city’s culture and cuisine. The exhibit is tied together by the perspectives of chefs and food journalists. According to Anisha Rathod, a farmer and educator, rice is the backbone of cuisines worldwide, feeding many families and communities.

In the United States alone, 4.8 million metric tons of rice were consumed in the last fiscal year. China and India combined account for half of the almost 520 million metric tons of rice consumed worldwide. Oscar Lorenzzi — chef of Contento, a Peruvian restaurant located in East Harlem — said that unfortunately, rice does not always receive the recognition it deserves.

“Rice never appears in a five-course, prix fixe in fine dining cuisines,” Lorenzzi said.

Nonetheless, rice’s pivotal role goes beyond restaurant menus. In Haiti, rice forms an integral part of the local cuisine. It is used in Diri Kole ak Pwa, a rice and bean dish. Steinhardt senior Shereka Dauphine spoke about the way rice keeps her connected to her family and Haitian background.

“I eat rice almost everyday,” Dauphine said. “I don’t really cook much, but my family cooks rice a few times a week and eats it with dinner pretty much on a daily basis.”

Dauphine also said that the way her mother prepares rice often determines the rest of the meal.

“A lot of different cultures see rice as a side dish, but in Haitian culture, rice is a very important part,” Dauphine said. “For example, whenever my mom asks what we’d like for dinner, she always asks us, ‘What kind of rice should I cook?’ instead of asking opinions on how vegetables or proteins should be cooked.”

Dauphine’s experience with rice matches the sentiment of James Gonzalez, co-owner of Puerto Rican restaurant La Fonda in Spanish Harlem, who says that the best rice dishes are “made in the best possible way, from head, heart and memories.”

I couldn’t agree more with Gonzalez and Dauphine. As a person who cherishes my Korean cultural background, I don’t generally consider a meal complete if it lacks a rice-based dish. At every Korean barbecue restaurant, you have not finished your meal until you have been served an iron plate, full of fried rice and topped with chopped kimchi, shredded mozzarella and umami-filled sesame oil.

At “Rice Stories,” Priya Krishna, a New York Times food reporter, says “Going to a restaurant is itself an experience.” If any of the Korean restaurants you visit fail to serve you fried rice after a meal, ask for some. If they say none is available, you might want to reconsider your choice of restaurant.

At “Rice Stories,” Krishna asked, “What would you put on top of a bowl of rice to make it a full meal?” For me, the answer is, “Just good rice.” While cooking a rice-based dish in the small kitchen space at Carlyle Court residence hall, I often find myself in a pinch — pressure cookers aren’t allowed. Without the pressure cooker to make the chewy yet soft and moist rice that I grew up with, I inevitably have to compromise some features of the immaculate bap. Although I recommend that you get an electric rice cooker if you plan to eat rice daily, here is my go-to recipe for cooking rice when all you have is a heavy-duty pot. And it should be heavy, because lightweight pots don’t reach the optimal temperature for flawless bap.

The perfect bap

Prep time: 30 minutes

Cook time: Approximately one hour

Difficulty level: Hard at first, but you’ll get the hang of it.

Ingredients

• 2 cups white rice (I recommend Nishiki Japanese Premium Medium Grain, but you can use whatever you have on hand)

• 2 ½ cups water

Instructions

1. Rinse two cups of rice thoroughly. Repeat this process until the water turns clear.

2. Soak the rinsed rice in cold water for at least 30 minutes.

3. Drain the water and transfer the rice to a large pot.

4. Add 2 ½ cups of water to the pot and close the lid.

5. Cook the rice on high heat. Once it starts to boil, remove the lid.

6. Cook the rice on medium heat for 10-15 minutes.

7. Reduce the heat to minimum intensity. Turn off the heat when you don’t see more condensation..

8. Let the pot sit with the lid closed for five minutes.

9. Remove the lid and mix the rice to prevent it from sticking to the walls of the pot.

Contact Daeun Lee at [email protected].