I will admit to being an avid reader of sappy romance books; it’s my guilty pleasure.

The stories are predictable, following the same basic narrative. It begins with the main character, usually a woman: She is sweet, smart and “not like other girls.” Then there’s the man, who is likely a player, but also smart and mean to everyone — except the main character, of course. Despite being the textbook definition of toxic, his soft spot for her makes me have a soft spot for him. And then, like clockwork, somewhere in the story, a third character is thrown into the mix, completing the classic — if not overdone — love triangle. He is the perfect gentleman, charming and funny, devoid of Boy No. 1’s toxic tendencies. I, however, never root for him. Quite the opposite, actually — I want him to lose. So badly. And I know I’m not alone.

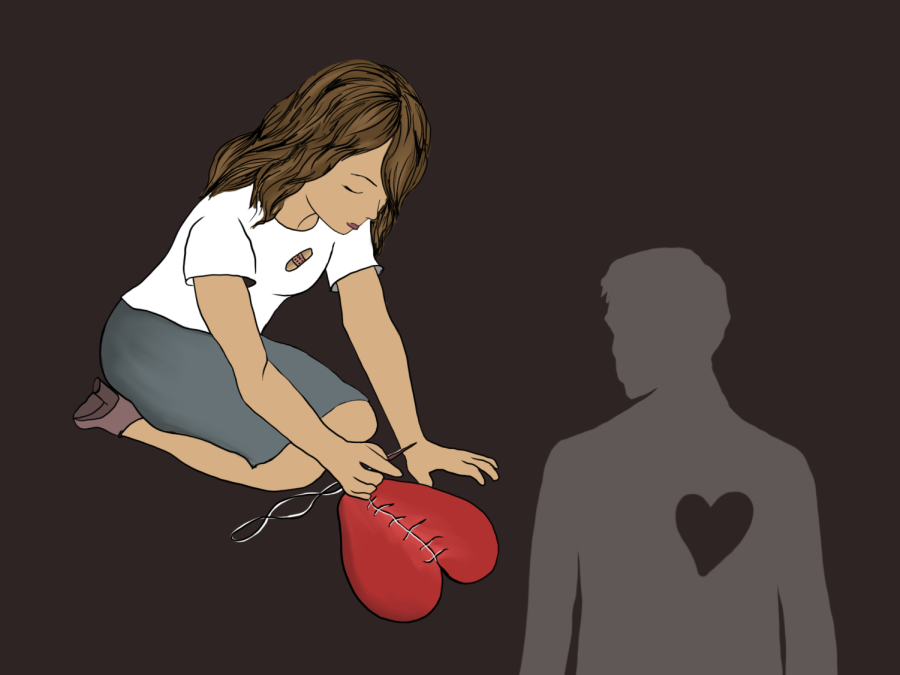

It is undeniably irrational, but a shared human experience. Most readers want the brooding one to win: the fixer-upper, the underdog, the broken person we often mistakenly believe we can make whole again. But what is behind this unbending attraction to those visibly flawed, and bad for us, and why are we so inclined to believe we have the power to fix them?

The short answer I like to tell myself is that flawed people are simply more interesting. There is a certain mystery as to why they are the way they are. What happened in their past that made them who they are today? Why do they have such thick skin? Why won’t they open up?

Determined to get answers, I spend more and more time with these flawed people — and my fondness for them grows. I come to consider them dear friends, and want to help them better themselves, for their own sake. This, however, may just be what I would like to believe, avoiding any and all deep analysis of the reasoning behind my choices. But I would be lying if I said I don’t wonder whether there’s a deeper meaning behind this phenomenon — my sick attraction and love for these individuals.

Tarra Bates-Duford, a psychologist with expertise in mental health and relationships, identified this phenomenon in her work, explaining that people often try to fix their romantic partner and want to make them a better person or partner. Fixers usually have unresolved personal issues, possibly tracking back to their childhood — and people who have endured childhood abuse or trauma are likely to suffer from anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. This sometimes leads them to believe that they are not lovable, not good enough or need fixing. As a response, they project these insecurities onto those closest to them.

In her work, Bates-Duford writes that many people who attempt to fix or improve their partners are subconsciously trying to remedy the problems they see in themselves. The fixers are trying to be what they wish they had themselves: somebody to help them during their struggle.

However, who doesn’t get along better with people who have gone through similar experiences? I asked LS sophomore Shreya Wankhade if she was more inclined to be around people who are considered broken — she quickly smirked and answered yes.

“You choose the people you surround yourself with based on what you have in common and shared life experiences,” Wankhade said. “It is often easier for me to relate to people who have some sort of trauma. It makes them more human.”

Maybe it is just empathy. Empathy is human nature, and we often see it as a first instinct. Our empathy helps us see the good in flawed people. It even helps us see the good in villains, drawing us to characters who are meant, by design, to be disliked.

Think of “Twilight” and the iconic love triangle of Bella, Edward and Jacob. Edward is completely and irrevocably in love with Bella, going as far as to call her his own personal brand of heroin. Isn’t that romantic? Even so, he treats her coldly in the first movie, trying to push her away. Later, in the second movie, when they are officially dating, he abandons her. He even goes as far as to make his whole family block and ignore her when she reaches out. Isn’t that even more romantic?

He is, essentially, a villain. Jacob, on the other hand, has loved Bella since the beginning, and has only shown her kindness. He welcomes her into the new town, asks her out on dates, introduces her to his friends as soon as he gets the chance and keeps her company every day after Edward abandons her. He does all of this without expecting anything in return.

In theory, Bella should choose Jacob. But Bella is a masochist and chooses Edward. Not only does Bella choose my favorite boy in cinematic history, but the general public does too. Seventy percent of Buzzfeed readers surveyed are team Edward.

So why do we love the people who fit the villain archetype? Yes, the fact that Robert Pattinson is playing this so-called villain makes it harder to choose anybody else. But that alone is not a good enough excuse. Ultimately, we desire a happy ending, even in complicated situations. Being with broken people creates a challenge, or a speed bump, in attaining this happy ending. But it does not take that urge away; if anything, it amplifies the desire.

It could be a coincidence if someone keeps getting into relationships where they feel the need to fix their partners. It could be by chance that all their friends are highly flawed, making them the shining star of the group. Maybe they just have bad luck with relationships and friendships. Sometimes fate just works in silly ways, right?

We are attracted to broken people and want to fix them because of our pasts, subconsciously attempting to fix our own personal issues. We are drawn to them because we want to feel better about ourselves — why else did Bella choose Edward over Jacob? Our natural human inclination to feel empathy for others is the main driver of this sort of attraction. We are fascinated with them because they present a challenge to the happy ending we constantly seek.

Our choices mirror our psyches and the harm that has been done to them, and our inclination toward fixer-uppers is no exception. As individualistic beings, our existence is naturally and inevitably self-centered, and everything we do is more a reflection of ourselves rather than of others — regardless of the alternate justifications we try to offer. Perhaps we’re all fixer-uppers, and it’s in this self-conscious nature that we can find the answer to this never-ending dilemma.