Bird-safe glass design at 181 Mercer saves wildlife and energy

Window collisions kill hundreds of thousands of birds every year in New York City. 181 Mercer’s architects are using specially designed glass with the intention of saving birds and energy.

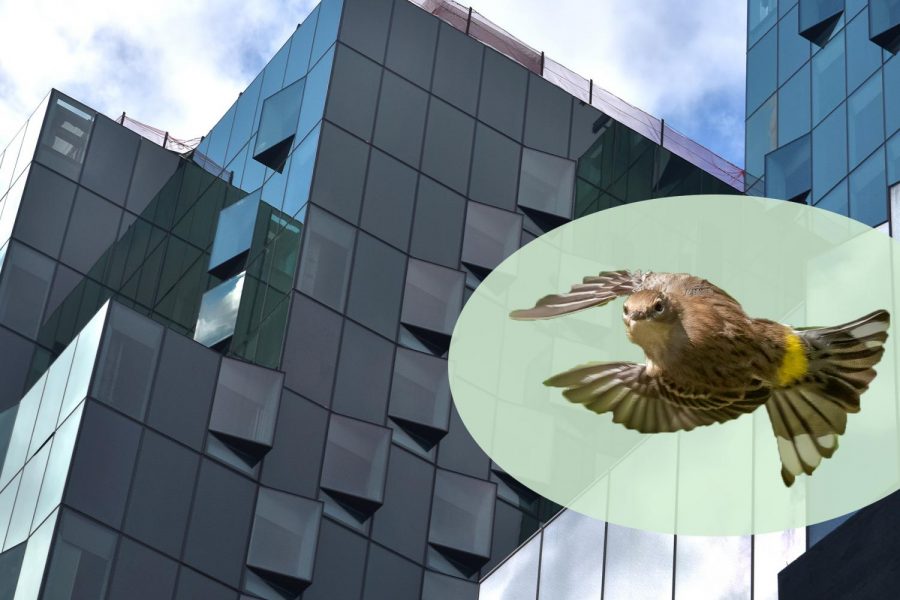

181 Mercer St., NYU’s new building, is being built with special glass windows to reduce energy usage and help prevent bird collisions. Up to 230,000 birds die every year in New York City from these collisions. (Staff Photo and Illustration by Ryan Kawahara)

October 18, 2021

Custom-designed glass on 181 Mercer Street, NYU’s under-construction multi-use building, will help prevent bird-window collisions — a serious threat to native bird populations in the area — while also reducing energy usage.

The design is intended to mitigate bird strikes, which frequently occur at buildings with clear or reflective glass. Research by conservation group NYC Audubon research estimates that up to 230,000 birds die in New York City every year due to collisions with glass. The American Bird Conservancy estimates that the annual avian death toll from collisions in the United States is close to one billion.

“That’s a huge number, especially when combined with all of the other things that are killing birds,” said Kaitlyn Parkins, an NYC Audubon conservation biologist whose work focuses on reducing bird-window collisions.

181 Mercer is the flagship development of NYU’s Core Plan, an expansion project initially called NYU 2031. Construction on the building commenced in March 2017, and the building is set to open in fall 2022 following delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Its exterior is almost entirely covered in fritted glass, a type of patterned glass created by applying ceramic frit to clear glass.

[Read more: Migrating birds imperiled by NYU buildings as spring approaches]

Christine Sheppard, director of the ABC’s glass collisions program, said that neither humans nor birds can actually see glass. Humans, however, have learned the concept of “an invisible barrier that can also be a mirror,” while birds seem take what they see literally — for them, reflections in glass are effectively indistinguishable from reality.

This means that conventional glass on buildings of any size can be a death trap. Tall glass buildings, though, are typically responsible for the mass mortality events that draw the most attention. Last month, buildings in the World Trade Center complex killed hundreds of songbirds after a heavy migration night.

“It’s something that many people are not aware enough of,” said Deborah Laurel, principal at architecture firm Prendergast Laurel. “Because glass has become one of our preferred building materials, it’s just very worrisome.”

Laurel, who works with groups like the ABC and NYC Audubon to promote bird-safe architecture, said that fritted glass can help prevent collisions by making glass more visible to birds.

Not all frit effectively deters collisions, though — the design must have high enough contrast and narrow enough spacing that birds are able to see the markings, but don’t try to fly between them.

With this in mind, KieranTimberlake, the architecture firm responsible for the design of 181 Mercer’s facade, increased the amount of frit and revised the glass pattern. Preventing bird collisions was a goal of the building’s exterior design plan and a key component of its sustainability strategy, according to KieranTimberlake partner Richard Maimon.

“181 Mercer’s design is directly tied to environmental responsibility,” Maimon wrote in a statement to WSN.

The firm created the final design in direct consultation with experts at the ABC and the Bird-Safe Building Alliance, including Sheppard. She said that the firm is known for designing with birds in mind.

“They did it right,” Sheppard said. “KieranTimberlake is one of the architecture firms that has really paid attention to this.”

The glass frit demonstrates KieranTimberlake’s commitment to sustainability on 181 Mercer, which Maimon said was designed in support of NYU’s Climate Action Plan.

“They’re very interested in conservation, in ecological and energy advancement, and they have been from the beginning,” Laurel said.

In addition to reducing bird strikes, 181 Mercer’s fritted glass contributes to the building’s sustainability strategy by reducing energy consumption. Because the frit reduces solar heat gain — heat generated from sunlight entering the building — cooling systems don’t need to work as hard, cutting energy use and costs.

Energy savings can also offset the initial costs of fritted glass, a concern frequently expressed by those reluctant to implement bird-safe design. However, Maimon noted that the frit added to 181 Mercer to prevent bird strikes did not add a significant cost. In general, Sheppard said, the cost of fritted glass is typically “relatively negligible” in comparison to overall construction expenses.

From a distance, the glass seems reflective. But from a few blocks away, a subtle, distinctive pattern on the glass — Laurel described it as “a fine sprinkling of snow” — becomes visible. Though the “glass box” style of skyscraper design is often unsafe for birds, Sheppard said that buildings like 181 Mercer show that bird-safe design doesn’t have to mean compromising on aesthetics.

“If somebody wants to build a bird-friendly glass box, they can do it, because the things that make buildings bird-friendly are materials that people have been using on buildings forever,” Sheppard said.

The bird-safe design of 181 Mercer predates New York City Local Law 15, which in 2021 started requiring exterior glass on most new buildings to meet bird-safety standards established by ABC research. The law was a major step toward creating bird-safe cities, but many buildings built or approved for construction before 2021 still present hazards.

“There’s definitely progress that has been made, but we’ve got a whole lot of buildings,” Laurel said. “We’ve still got a whole lot of work to do.”

Buildings with large glass exteriors across from abundant vegetation or urban parks are among the most dangerous to birds in the city, according to a 2009 study. Many NYU buildings fall into this category — the Kimmel Center for University Life and Bobst Library reflect Washington Square Park, and Warren Weaver Hall mirrors trees along Mercer Street. Campus buildings are not monitored for window collisions, but crowdsourced data suggests that they occur frequently.

For existing buildings that are unsafe for birds, experts recommend retrofitting bird-safe glass to mitigate the danger. Patterned adhesive films, usually in stripe or dot designs, are typically used to remediate existing windows. The main obstacles to implementation, Laurel said, are design preferences favoring large windows and insufficient public awareness of bird collisions.

“It’s going to take some time to get everybody on board to understand that we have to treat all of that glass that’s already installed, or at least the majority of it, to really begin to reduce the fatalities,” Laurel said.

Retrofits can be extremely effective — at the Jacob K. Javits Center on the West Side, for example, replacing conventional glass with fritted glass reduced collisions by over 90% at a previous hotspot of bird death. With a new green roof, renovations transformed the building from a lethal hazard to a potentially usable habitat for wildlife.

Creating bird-safe buildings like the renovated Javits Center and 181 Mercer allows developers to surround buildings with habitats that benefit people as well as birds. Without the fritted glass, birds drawn to the landscaping on and around 181 Mercer would have been put in danger.

“It’s so important that you’re not creating an ecological trap,” Parkins said.

With KieranTimberlake’s bird-friendly design, though, the building’s green spaces are safe for both birds and humans to enjoy. Helping birds benefits people as well, Parkins said — people won’t have to see dead birds at their school or workplace, and having more birds around has ecological and emotional benefits.

“I think that there’s inherent value in saving birds, but you can look at it from a biodiversity perspective,” Parkins said.

Diversity of birds and birdsong has been linked to human wellbeing, and ecosystems with a greater diversity of species are more resilient to extreme weather and other natural disasters. As Sheppard put it, “birds are good for people.”

Despite these benefits, bird-safe design remains rare. Although it is beginning to catch on, scientists are still left without much field data. Groups like the ABC conduct tests of bird-safe glass designs, but Sheppard said that these evaluations are not designed to replicate real-world conditions.

Light and reflectivity conditions change throughout the day, making it difficult to predict exactly how effective a glass design will be. When architects design buildings like 181 Mercer with birds in mind, they not only save birds but also help researchers learn which designs work best in practice.

“The more of these installations we see, the more excited we get, because that means our research is implemented on actual buildings,” Laurel said.

Though before-and-after data on retrofitted windows is the most scientifically valuable, it’s difficult to collect, meaning that data from new buildings is useful as well.

Bird-safe design is increasing in popularity, but its adoption is not yet widespread. Unlike most new buildings, 181 Mercer’s design seeks to balance function, aesthetics and sustainability, making it an exemplar of bird-safe architecture, according to Parkins.

“It sets a standard that other buildings, other architects can aspire to,” Parkins said.

A version of this story appeared in the Oct. 18, 2021, e-print edition. Contact Alex Tey at [email protected].