‘Gone Girl’ depicts strong antihero

November 6, 2014

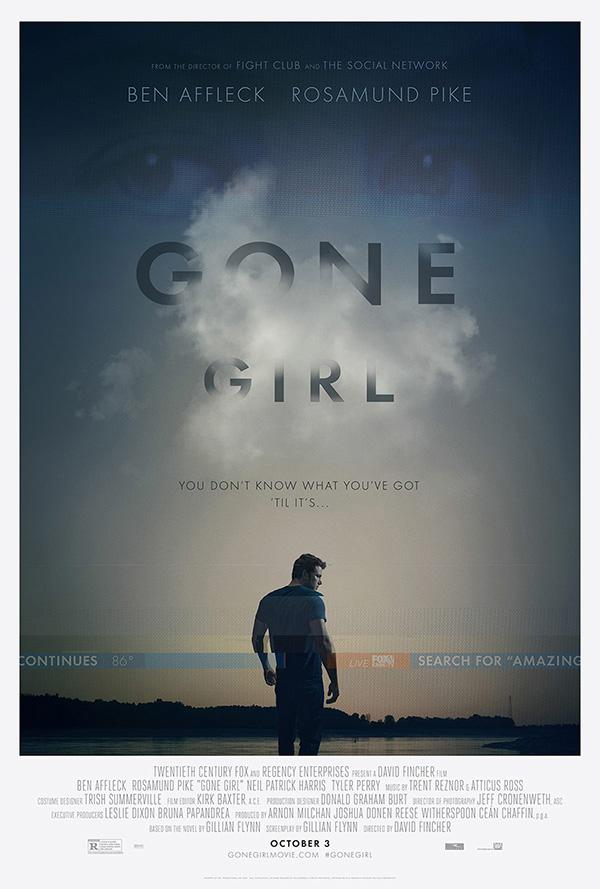

Given David Fincher’s track record of films that focus on issues of masculinity (“Fight Club”) and have few, if any, noteworthy female characters (“The Social Network”), it would not have been off-base to assume that his latest, “Gone Girl,” would end up the same way. But “Gone Girl” is not Fincher’s story, it is Gillian Flynn’s. The author of the original novel and screenwriter for the film adaptation self-identifies as a feminist, but she has combated accusations of misogyny for the malicious tendencies of the protagonist, Amy Dunne.

The most common criticism thrown at “Gone Girl” is that Amy represents strawman anti-feminist arguments — a collection of a misogynist’s worst fears. She frames her husband Nick for her murder, purposefully reports false rape accusations and has a sociopathic intent on destroying her husband’s life. But she is also a complex and multidimensional female character, the kind that is rarely depicted on screen.

It is assumed that for a film to be feminist, the female protagonist should be conventionally strong — unwaveringly empathetic and moral. This viewpoint is detrimental to the cause. Female characters should be allowed to be conniving, deceptive and morally ambiguous, just like Amy. Authors and filmmakers should not be limited to creating one type of woman in their art. The goal should be a wide spectrum of characters with heroes, antiheroes, innocent victims, cunning evildoers and characters that fall somewhere in between. As long as the persona is well-crafted with a degree of complexity and is not reduced to being a token, that character deserves a voice.

Amy is not a stereotype. In fact, she openly fights against the archetypes she has had to portray her whole life. In the novel’s well-known “Cool Girl” passage, she expresses her disgust at having filled the role of the sought-after girl who can hang out with the guys, drinking and watching sports. She blames her husband Nick and the rest of society for forcing her into this role, letting it serve as her underlying motivation for framing him. In fact, by the end of the film, Amy has reduced Nick to the role of a supportive, passive husband.

Amy is an evil character, but more importantly, she is an interesting one. She has layers and complex motivations, which is what makes “Gone Girl” empowering. She is not one note. Rather, she is a rare female antihero that Fincher beautifully transfers to film.

A version of this article appeared in the Fall 2014 Arts Issue. Email Zach Martin at [email protected].