The 1970s to 1990s saw the boom of the shōjo genre, a category of Japanese manga primarily for young women. This included the rise of classic titles like Naoko Takeuchi’s “Sailor Moon” and Clamp’s “Cardcaptor Sakura” — stories propelled by strong-willed heroines with guileless determination, magical abilities and an indomitable spirit. But during the same time period, an alternative manga artist scene emerged representing a different heroine: ordinary women and their mundane yet oppressive realities.

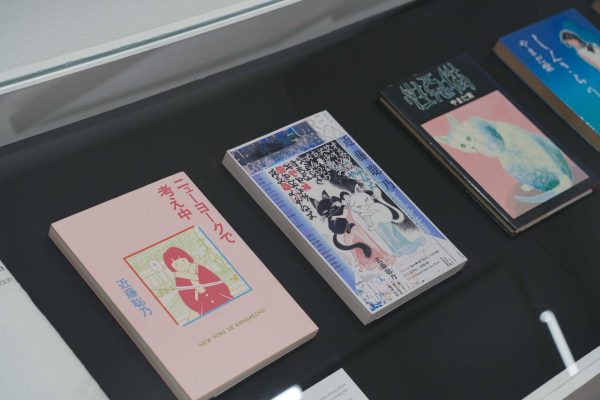

The exhibition “Beetles, Cats, Clouds” — presented at the 80WSE Gallery near Washington Square Park — dives into the manga scene from the 1960s to 2000s, showcasing the works of Tsurita Kuniko, Yamada Murasaki and Kondoh Akino. From original pages of published panels to sketchbook drawings, the exhibition tells a story not simply of magic or action-packed fight scenes, but of gender norms, patriarchy and womanhood.

Murasaki’s illustrations from her 1971 one-shot “Oh, the Ways of the World” tells the story of a restless young woman, angry at the uptight nature of society. One page centers on her face, expressionless and static, with faceless girls in the background — depicting the feeling of being trapped and overwhelmed by the expectations of womanhood. Murasaki’s artwork stems from her struggles growing up in a conservative household and discovering her creative and social identity.

After Murasaki married and had children, she became known as a “housewife cartoonist” for her unconventionally honest portrayals of motherhood. Her panels reflect this focus, with candid, sentimental depictions of the turmoils of domestic life. Through her work, Murasaki verbalizes the universal, unspoken struggles of women, unapologetically taking up space in a patriarchal system.

Alternatively, Akino’s works aim to bend reality. The second room of the exhibition displays a cathode ray tube television display that plays three hand-drawn animations, each running from four to six minutes. In “Ladybird’s Requiem,” Akino’s recurring character Eiko, a young girl, plays with ladybugs, sews buttons into her dress and dances in a dreamy landscape. Each shot becomes more unnerving as clones appear and the buttons come alive, merging with the ladybugs. Akino’s storytelling is nonsensical, disturbing and endlessly captivating.

In a 2011 interview, Akino explained that Eiko serves as a rewriting of her own childhood, turning her nightmares into amusement. This also applies artistically, giving Akino agency over her imaginings and anxieties, now transformed into dancing ladybugs.

Kuniko’s 1974 work “Yuko’s Days” turns the viewer toward the solitude of illness, telling the story of a hospital patient navigating life in a desolate medical facility. The panels were drawn near Kuniko’s death, when she spent weeks at a time in hospital rooms after being diagnosed with lupus. Compared to the typically polished, action-packed and bright stories of manga, Kuniko’s are dark, personal and gritty.

Before “Yuko’s Days,” a table displayed one of Kuniko’s later works, “Flight.” Laying bare, her soul spilled onto the pages in abstract, aggressive ink strokes and shaky lines. Kuniko continued drawing despite hospitalization, and in 1980, fulfilled her lifelong dream of having her work published in a mainstream seinen (“young men’s”) magazine. She persisted as an artist, pushing through illness to continue presenting her work, even as her body deteriorated.

“Beetles, Cats, Clouds” is not only powerful because of the artists’ impact on manga’s gender conventions, but also because of their commitment to their art, despite industry rejection. Murasaki, Akino and Kuniko didn’t need to pen magical heroes in their stories — not when the heroine lived within them.

“Beetles, Cats, Clouds” is on view through Jan. 24 at the 80WSE Gallery. Admission is free for NYU students.

Contact Ella Jiang at at [email protected].