The Foreigner

Tensions arise for Eugene Hu when he stays at his old college roommate’s house in Connecticut during the pandemic.

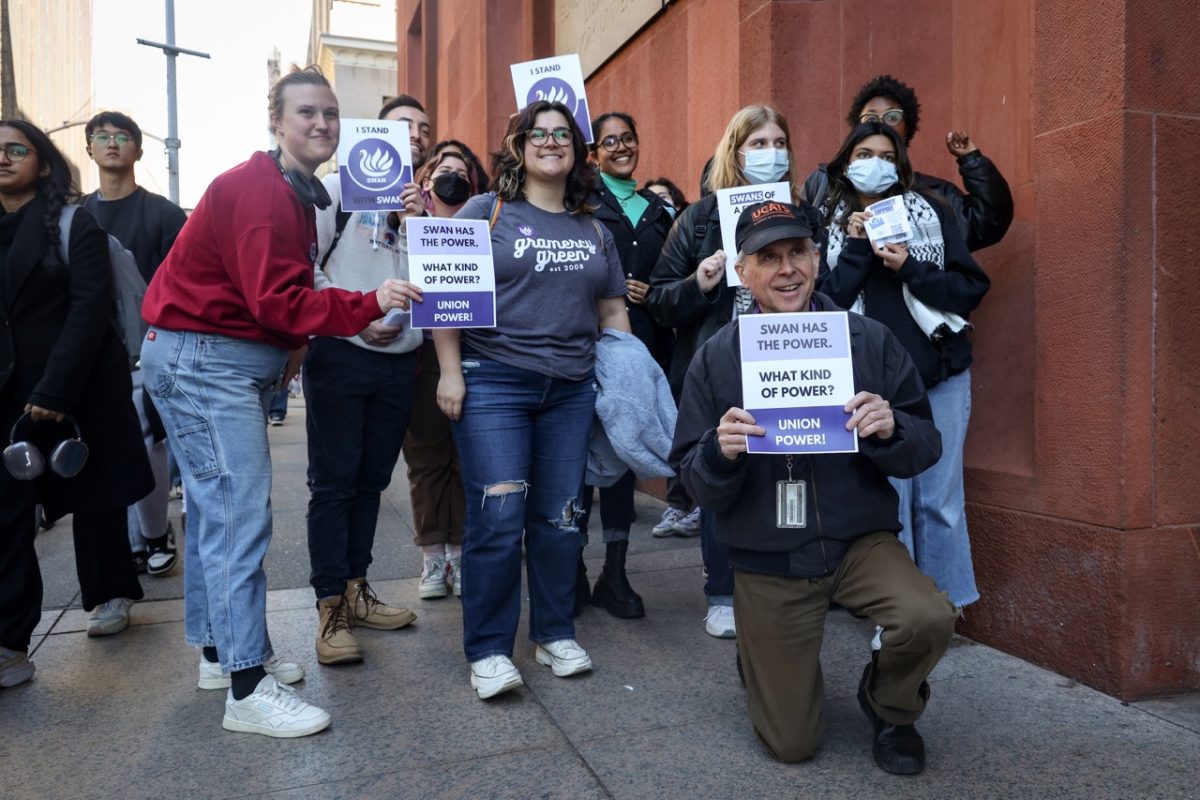

A seemingly idyllic sidewalk in Middletown, Connecticut. (Photo by Eugene Hu)

May 3, 2021

“I’m boycotting your Chinese bricks!” Tim said to me.

It was dusk in Middletown, Connecticut. I was playing Settlers of Catan with my college roommate and his father. We were trading bricks, but our business negotiations were not as smooth as I hoped they would be. When Tim said this to me, my heart told me that I was in no position to speak out against a man who was only screwing with me in a game of Settlers of Catan. I genuinely did not feel offended, but my brain said that I should tell him that this was an incredibly insensitive thing to say, that you can’t say that kind of shit in this day and age. What I learned in high school told me that I ought to be angry and outspoken in this sort of situation. My more socially conscious peers told me time and time again that jokes shouldn’t just be jokes, since jokes are the perfect gateway to casual racism, but I held my tongue.

“OK, for that, I’m not trading with you for the rest of this game,” I said. I maintained a smirk so that Tim knew I was not really upset.

“Sorry, that was my Trump impression,” Tim said.

***

When the world started classifying the coronavirus as a pandemic, universities dished out eviction notices by the dozen. The barren New York streets at that time reminded me of a childhood video game of mine called “New York Zombies,” where you play as one of the sole survivors of a zombie apocalypse and traverse Central Park, Holland Tunnel and the New York subway system while fighting off the walking dead. The apocalyptic vision of the Big Apple as a ghost metropolis had never felt more tangible. Perhaps it was because of the novelty, but I grew to like that idea.

With one week left to pack my stuff and find shelter, my college roommate, Harry, offered me a place to stay in his house in Connecticut. The offer took me by surprise, given that he was as talkative as a rock for the majority of my first year. His parents, Tim and Kate, were less exaggerated versions of Homer and Marge Simpson — an everyday man and his wife, who showed affection towards each other with nonstop teasing.

I kept in touch with my parents in China via Skype. They insisted that I do two things. First, they wanted me to use the experience of being in the Gregory household from March to August as fuel for future writing projects that recalled the time when the world had gone to shambles. Second, they wanted me to get along with the Gregory family, because, according to them, “no one has ever done a greater favor for us in our lives.”

I was a vampire. I really didn’t care much for going outside, so I didn’t get to see the outside world in shambles. There was always a roof over my head. I only found cause to be angry about the little things that shouldn’t have made me angry, and because of that, I couldn’t always get along with the Gregory family.

***

One night, I made the egregious mistake of eating buffalo wings with a fork. Tim stared at me with bulging eyes and a slack jaw, which made him look like a cartoon character.

“Why aren’t you using your hands?” Tim asked me.

“Force of habit.”

“Ok, well, if you go to any other place in this country, and they see you eating wings with a fork, people are going to think you’re a lunatic,” Tim said.

My brain began to tingle. Just like when we played Settlers of Catan, Tim felt the need to constantly remind me that I was a foreigner. He was not wrong. I was a foreigner, but I did not want to feel like one.

“Honestly, I don’t care about what other people think about me,” I replied. “This is what I’ve always done. I don’t like getting my hands dirty.”

“Are you saying we’re savages then?” Kate chuckled.

“Alright, but if you ever go to a bar, you’re gonna get mocked by everybody else,” Tim said.

On one hand, I didn’t want to be a foreigner. On the other hand, I didn’t want to give into the pressure to assimilate. My heart said to not make a big deal out of it. After all, eating wings with a fork is a trivial thing, but my brain was heating up like an impassioned furnace. It was too busy trying to reconcile the desire for individuality with the desire for a sense of belonging. It couldn’t help but overheat. I couldn’t stay silent, so I let out a crude exhale. It was one of those exhales people do when they want to say “fuck off” without saying “fuck off.”

“Whatever,” I said. We resumed dinner after about ten seconds of peace. It was as if nothing had happened.

“How are classes, Harry?” Tim asked.

He gave a tentative nod and said, “Alright.”

Harry was the looming background character in the Gregory household. Regardless of whether he felt gratitude or disdain, he never raised his voice on any occasion. I did not share his talent. We never talked much, but I appreciated him simply for being there. Maybe it’s because an extra presence helped when people were forced to remain distant, or perhaps I merely envied him for his stoicism.

These were the early days of staying at the Gregory household. At that point, my parents made a habit out of exchanging emails with Tim and Kate. In every email, they emphasized, somewhat paradoxically, that “words cannot express how grateful they are” that the Gregorys took me into their home. When my parents heard about the incident with the buffalo wings, they said, “That’s a little out of line. You should apologize tomorrow.” When I told Tim the next day that I was unnecessarily aggressive after I heard his comment, he simply laughed it off.

“Oh, it’s okay,” Tim said, “I thought you were joking. I didn’t think you were actually worked up.”

“Well, I’m telling you now,” I responded. “I’m sorry.”

I wasn’t sure if it was me or my parents speaking.

***

We went a few weeks without tension at the dinner table, not even on the night when Tim set down a massive platter of pâté chinois and told me, “We’re gonna turn you into a Frenchman.” This time, my mind insisted that it was a reference to colonialism. Like the last incident, there was the pressure of assimilation floating in the air. My high school peers repeatedly said that those were toxic ideas, that nobody has the right to dictate our identities or changes in our identities except ourselves. On that, I could not have agreed more. Why did I have to be turned into a Frenchman? Why did I have to be turned into anything?

I was too busy taking in the flavor of the dish to care about that. The mashed potatoes, corn and ground beef combination was something I never tried before, so I simply nodded and complimented Tim on his culinary skills. Like Remy in “Ratatouille” when he mixes a strawberry with cheese for the first time, I forced my brain to succumb to the flourish of dancing colors. My heart felt nourished, and I simply allowed the taste of the pâté chinois to make my thoughts dissipate.

This was the way things should be, I felt. A family, plus a guest, coming together after a long week of working online. There was no need to think.

Every Saturday, my mother asked what we had for dinner during our Skype meetings. She never heard of pâté chinois before. When I described what it was like, she immediately remarked how desperately she wanted to meet the Gregorys, because once again, emails failed to communicate just how much gratitude she had.

“I love how you talk about the Gregorys like messiahs,” I said. The sarcasm transferred over.

“Do I?” she said. “I never thought of them as messiahs. I think of them as people that have done us a huge favor. If I was in that position, and my son’s roommate needed a place to stay, I don’t think I could’ve been that generous,” my mother said.

***

Of course, tensions didn’t always rise at the dinner table. On the night of the Democratic National Convention, I was busy in my room watching Daredevil beat yakuza members to a pulp with his bare fists. When I got thirsty and went downstairs to grab a Pepsi, Tim asked me if I wanted to catch the DNC on TV with him and Kate.

“Yeah, pass.”

“Well, it might be useful for you to learn about American politics if you wanna live here in the future.”

Maybe it was the idea of temporarily giving up watching “Daredevil” that ticked me off. Maybe it was the fact that American politics had been the only thing on my Instagram feed for the past few weeks, but my head could not take that statement. My brain and heart were like two sumo wrestlers pushing back against each other. In this case, the former barely managed to shove the latter out of the ring.

“Oh my god… You gotta stop treating me like a foreigner. I’ve seen enough American politics as it is. To be honest, it’s almost getting on my nerves.”

“I’m not treating you like a foreigner!” Tim said.

A brief, quiet moment.

“You know, you’re really sensitive sometimes,” Tim responded. “I feel like you see offense where there is none.”

He hit the nail on the head with that one. This was the perfect time for an escalation, but Tim was so spot on with his diagnosis that it didn’t happen.

“I guess you’re right, I’m sorry.”

This time, I did not tell my parents.

After a perpetual cycle of churning out sociology essays, having political discourse over plates of mac ‘n’ cheese, hiking around the town’s various parks, learning how to paint a house and rewatching the hallway fight scene from “Daredevil,” school was about to start again. That was when Kate began to poke fun at me by saying, “I’m sure you’re relieved that you won’t have to put up with us anymore. You must be like, ‘Oh my God. Finally, I’m rid of the Gregorys.’” I smiled out of politeness, since I wasn’t sure if she was joking or being serious.

My heart tightly squeezed my chest. There was no way that it was going to let me feel genuine relief for leaving the people who gave me more than I could have ever asked for. Of course, that could have been the stranglehold put on me by my parents’ desires. My brain was asleep. Packing bags didn’t exactly count as a mental workout.

Tim drove me back to NYU on an overcast day. I couldn’t remember much about our last discourse, except for when he asked me a question about people who were averse to the idea of wearing masks.

“Of course, I’m not defending it, I’m just not surprised at all. It’s a shitty mindset to have, but when you take even a little bit of freedom away from people, they will resist,” I said.

“I just don’t see how making people wear a mask is taking away freedom,” Tim answered. “It’s not that big of a deal. I mean, some places can’t even get their hands on masks, and it’s unfortunate. I think people sometimes mistake inconveniences for maltreatment because they don’t know how good they have it,” Tim said.

The memories of my spats with Tim struck me like an aggressive ocean wave. My brain short-circuited and my heart throbbed.

This is exactly everything that is wrong with you. These people take you in as a guest. No, not as a guest. They take you for one of their own. They see you as a part of their family. What do you do? You throw tantrums when the words don’t sound right, don’t taste right, don’t feel right. You don’t wanna be a part of their family, but you don’t wanna be a part of anything else, either. The food, the hikes, the painting, the discourse. How much was it worth to you?

This continued for the remainder of the car ride to New York.

***

We arrived at my dorm in the West Village and pushed my suitcases to the front of the building. Before I bid Tim farewell, I took in the view of the streets. A small part of me was looking forward to seeing New York as a ghost town again. There was an eerie satisfaction in seeing myself as one of the few survivors of a worldwide transfiguration. Unfortunately, at that point, it didn’t look much different from what it looked like before the pandemic. The only difference was everybody looked like they were ready to kick some ass with their masks covering the bottom half of their faces. The aura of mystery and isolation that I experienced in March completely vanished, and a feeling of disappointment washed over me. Things became vibrant, and I felt worse because of it.

Only then did I fully realize why I had always been a foreigner.

My original plan was to give Tim a fist bump or a touch on the elbow to adhere to the social distancing rules. I even rehearsed the lines in my head: “Thank you, Tim, for everything. I would hug you, but I wouldn’t want to get you sick by accident.” Before I could blurt out anything, he hugged me first. He had never done this before.

And for an instant, I had no thoughts, I had no feelings, I had no overwhelming, constricting sensations. I didn’t push him away, and I didn’t hug him tighter, either. There was only the embrace.

Email Eugene Hu at [email protected]