Ocean Vuong captivated the Skirball Center for the Performing Arts on Thursday night, reading from his latest novel “The Emperor of Gladness” to around 700 attendees at a free public event hosted by the NYU Creative Writing Program.

Six years after “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous,” the creative writing alum and professor’s second novel debuted No. 2 on The New York Times Bestseller list. Named in Time’s annual list of 100 emerging leaders last week, Vuong spoke to WSN before the event about balancing his dual roles as a novelist and creative writing educator.

“I don’t step into the class as Ocean Vuong, the writer,” he said. “Students, of course, see that, but if you step in with your achievements, it taints the class — teaching is a separate art that has to be developed.”

Before his reading, Vuong told the audience that “The Emperor of Gladness” is set in 2009 at the start of what is now called the opioid epidemic, introducing a scene where protagonist Hai witnesses an overdose for the first time.

CAS sophomore Cara Uypeckcuat, who was unfamiliar with Vuong’s work before attending with a friend, said the passage left her wanting to read the book.

“He had pauses and you could feel the emotion,” Uypeckcuat said. “I lowkey wanted to cry a little bit even without the context of the full novel because the way he embodied the character was really moving.”

Though his novels have topped best-seller lists, Vuong — a T.S. Eliot Prize winner with two poetry collections and two chapbooks — is more at home with poetry than prose. At the event, he performed surprise readings of “16,” the only poem he wrote “during the last election cycle,” and “Theology,” which previously appeared in The New Yorker.

Liberal studies first-year Haseeb Haider has read Vuong’s poetry since ninth grade and credits the author as a reason he chose to attend NYU. A Pakistani immigrant hoping to pursue writing professionally, Haider said Vuong’s success helped him convince his parents that creative writing could be a viable career. He was especially drawn to “16,” which Vuong said “conflates” the voices of a 16-year-old boy and Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president.

“I found that he used temporality in a very interesting way,” Haider said. “As a 17-year-old myself, hearing some of that voice along with the voice of one of this nation’s most revered members is a very interesting thing to see poetically, and seeing that kind of thing happen in real life was inspiring.”

For Vuong, the evening embodied a larger message about who gets to be an artist. In his interview with WSN, he pointed to a line that appears in the author biography of all his books: “Born in Saigon, Vietnam, he currently splits his time between Northampton, Massachusetts, and New York City.”

“In that sentence is an entire historical biography, but it’s also a story of survival,” Vuong said. “An event like this is a testament that you can come from the projects, you can come from food stamps, you can be the first generation to go to college, you can be the first to read, you can be a refugee — you can be all those things that you can’t control and yet you can still be an artist.”

For the second half of the event, Vuong sat down with Creative Writing Program Director Deborah Landau for a conversation that ranged from recounting his early days as a performer to reconciling ego with Buddhist practice.

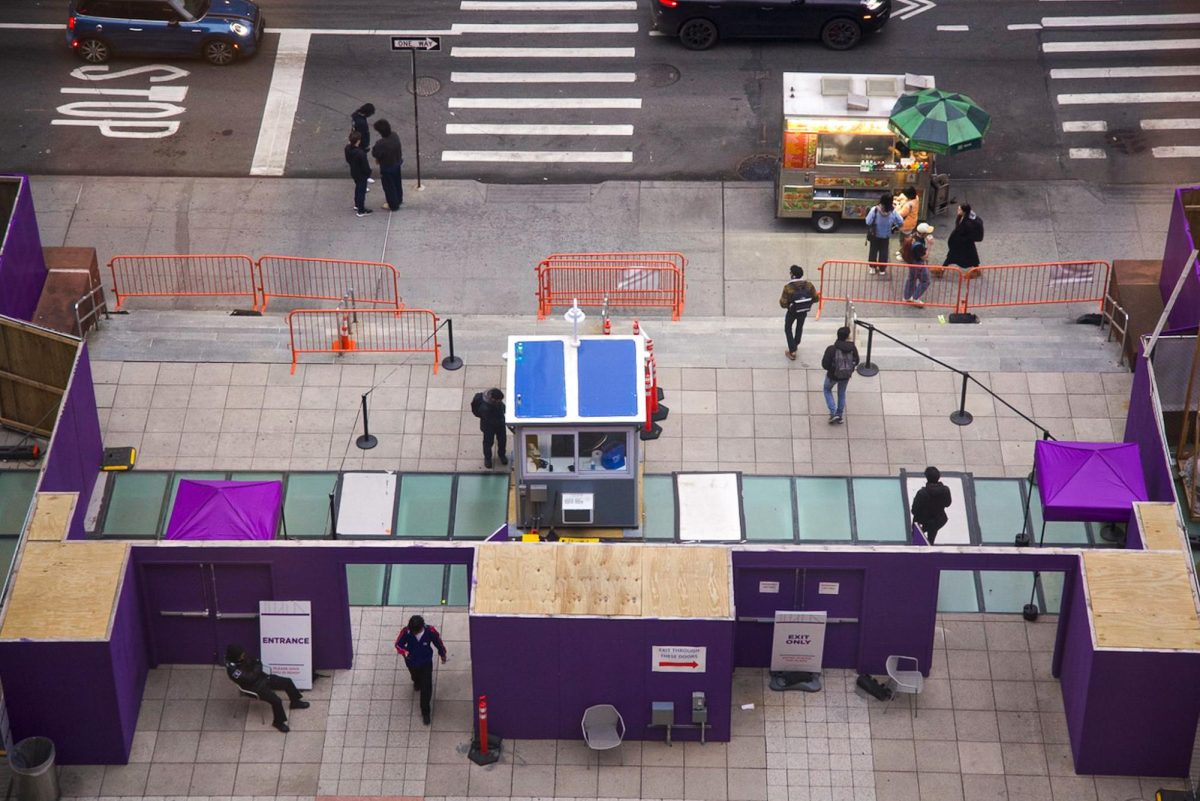

When Landau asked about his open-mic performances at Bar 13 in Union Square during college, Vuong recalled sharing a “horrible poem” about a one-night stand that took an unexpected turn. That evening, Vuong lost sexual interest after learning the other person was a weatherman — a moment that ultimately turned into a “beautiful experience of queer grace.”

“I felt like I betrayed the enterprise of the hook-up,” Vuong said. “I did not know that education and tenderness and beauty can exist anywhere. To me, there was something so queer about that because it was about alterity.”

The conversation moved through his growth as a poet, what happens in his classroom and the differences between writing novels and poems. Vuong then turned to politicians, arguing that they use the same literary techniques his students do — but deploy them for votes, profit and corruption rather than to express feelings like bewilderment and joy.

“Trump is a poet, hate it or love it,” Vuong said. “‘Make America Great Again’ is a kind of linguistic hallucination because you’re telling them you’re going to restore their childhood — a time before they were ever fired from their job, before they realized that they were living on the wrong side of town, that they were poor, before they lost their pets, their grandparents, before they got their heart broken.”

In his final remarks, Vuong challenged what he called an American double standard: Poets are told to be humble, while those making bombs or maximizing Wall Street profits never face similar demands. Poets must give themselves “permission to be formally ambitious,” Vuong said, because “the people driving our world off a cliff are never humble about where they’re going.”

Contact Krish Dev at [email protected].