ChatGPT is here — what’s NYU doing about it?

“The existence of a well-written paragraph is no longer evidence of human effort,” reads a memo to NYU’s schools, warning them of the plagiarism possibilities that ChatGPT and AI programs like it bring to the classroom.

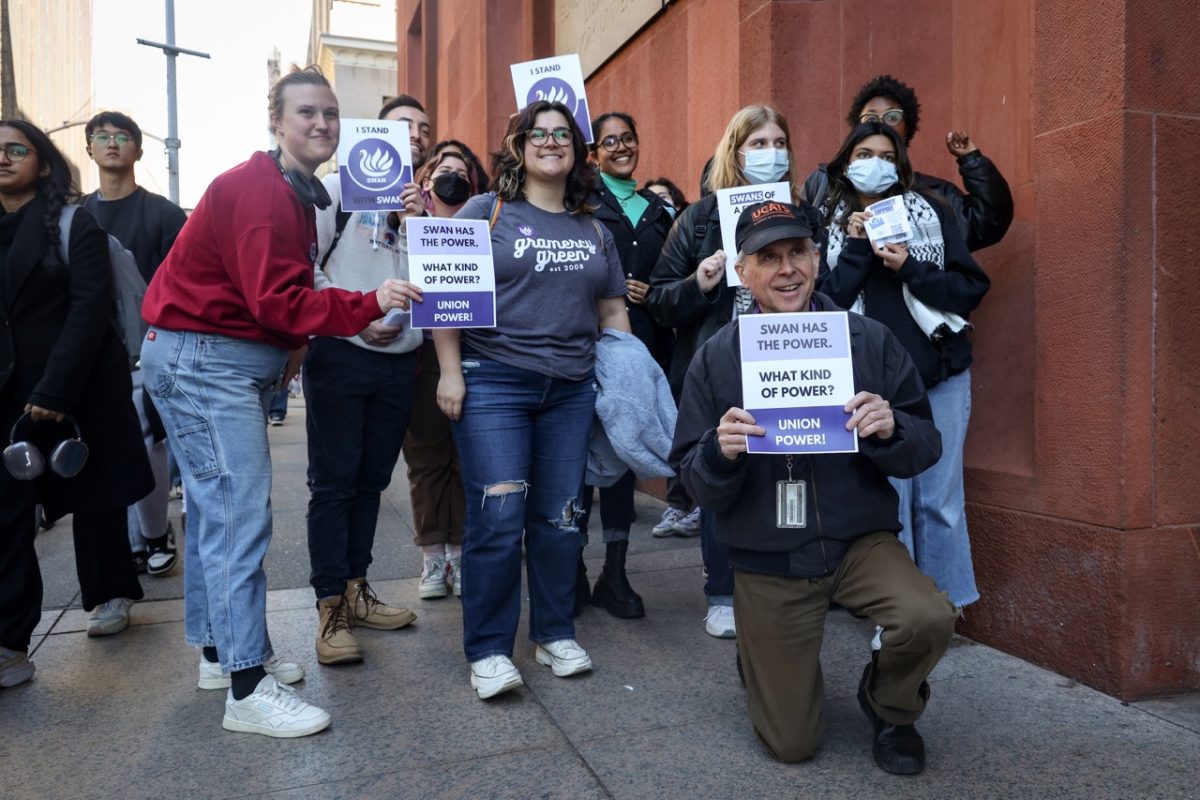

NYU’s academic integrity policy does not currently mention the use of ChatGPT in coursework. (Kevin Wu for WSN)

February 2, 2023

ChatGPT, the easily accessible, uncannily human artificial intelligence program that can quickly generate text from a prompt, has caused a stir at universities across the country. Faculty and administrators are split on whether it can be used as a learning tool, or if it is a vehicle for plagiarism that has no place on a college campus. NYU does not yet have a universal policy that covers the use of AI tools in the classroom, but some individual professors have included guidelines in their syllabi for the first time this semester.

As part of its response to the AI, NYU has also created a working group of 50 faculty and staff to help give instructors guidance about ChatGPT. Clay Shirky, the vice provost for educational technologies, who chairs the group, said the decision to create it was made after some faculty detected the use of AI by their students as early as December of last year.

“The technology here is not what’s new — what’s revolutionary, in fact, is usability,” Shirky said. “Almost everyone understands that this change has already happened. Faculty are now adapting, and that adaptation over the long term is going to include a conversation with students class by class.”

This semester will serve as an experiment for how ChatGPT can be used in a classroom setting at NYU, and the results will be used alongside student and faculty input to determine guidance for the next semester, according to Shirky. Rules governing the use of AI in the classroom will change and evolve over the next few years, he added — a consequence of the breakneck pace at which the technology is advancing.

On Jan. 21, the provost’s office, which is responsible for the administration of academic standards across the university, sent a provisional note offering recommendations for adapting classes to the existence of ChatGPT. The guidelines, which focus on written assignments, give faculty three potential responses: looking for AI use in completed classwork, creating assignments that are difficult to complete with AI or allowing the use of AI for coursework with restrictions.

“For faculty who teach writing, the essential change is this: The existence of a well-written paragraph is no longer evidence of human effort,” the note reads. “There is no short-term fix to this revolution in usability of these tools. Instead, we will be gradually but continually adapting our practices for some time.”

Other universities are taking a similar approach, opting to adapt to AI tools rather than ban students from using them. One professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School even requires students to use ChatGPT, though he does require them to disclose where and how the AI was used.

The note also advises faculty to exercise caution in using programs designed to detect text written by ChatGPT, explaining that they are sometimes inaccurate. OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, has described their own AI-detection tool as imperfect.

In one French language course in the College of Arts & Science, all essay assignments must now be completed during class to prevent the use of ChatGPT.

Reva Sharma, a first-year student in the course, said the change has made coursework more difficult. Her other professors are more open-minded about the use of AI in the classroom, though — in one of her writing classes, the professor had students compare their writing with that of the AI.

“My professors have said that we shouldn’t use it to write our actual essays, but we were using it in class today,” Sharma said. “We all had to pick a movie to write an essay on. First she had us individually write a two-sentence synopsis of the movie, and then she had us ask ChatGPT to do the same thing for all of our movies.”

Professors started adapting their courses to ChatGPT before this semester, according to Richard Xu, a teaching assistant for a CAS computer science course. Xu said that the class’ instructor ran fall final exam questions through ChatGPT to ensure that they could not be solved by the program.

Dino Sossi, a professor who teaches an AI course at the School of Professional Studies, said he is allowing students to use AI tools to complement their classwork. At the same time, he said that he is making changes to his assignment prompts, requiring them to be more personal — requiring details an AI wouldn’t know. He hopes that in this way, students will use both technology and their own experiences in their work.

“NYU students are creative, hard-working and ambitious,” Sossi said. “If we can help them think of ChatGPT not just as a valuable tool to engage with academic disciplines, but also as a means to explore the world and the ethical implications of new technology, we will have done our job.”

While NYU’s academic integrity policy does not explicitly address the use of ChatGPT in coursework, it does prohibit students from violating academic guidelines created by specific schools and departments. It also prohibits students from submitting work that they did not create as their own.

Robert Ausch, a professor teaching a course titled “Cognition” in the psychology department this semester, said that his department has not yet issued guidelines for using ChatGPT in the classroom, but the program has not changed the way he runs his class. Ausch said he thinks it would be difficult for a student to use ChatGPT in his course because his exams are very specific to what he discusses in lectures.

“I don’t think it is the faculty’s job to ‘catch’ students — I don’t think of my students as children who need to be supervised,” Ausch said. “Life will eventually teach them that some shortcuts might work some of the time, but eventually if you can’t do what you’re supposed to be able to do, the world will notice.”

Contact Carmo Moniz at [email protected].