Grids of black-and-white portraits fill the walls of El Museo del Barrio alongside footage on old TV screens in the center room. The museum is a leading institution in showcasing Puerto Rican and Latin American culture and history. Cuban-American author and educator Coco Fusco’s exhibition, “Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island,” intertwines the history of violence against Latine people with a contemporary hope for freedom.

In Fusco’s first U.S.-based retrospective, El Museo showcases three decades of her work.

The exhibition connects media archives to ongoing issues of political surveillance and institutional control. Fusco drives a conversation around colonial legacies and their lasting impact on Latine communities today, amplifying Indigenous Latine stories of resilience through her art. The title, “Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island,” expresses not just a hope, but an expectation for freedom. The island, referencing Fusco’s Cuban heritage, symbolizes her vision for a postcolonial Latin America — autonomous, protected and uncaged.

One of Fusco’s most striking works is “Dolores from 10 to 10.” Between the first and second room, a tiny surveillance screen showing footage from a camera juts from the wall, with cords dangling beneath it. Silent scenes of grainy, black-and-white footage shift continuously: an empty stairwell, a man walking down a hallway, a woman pacing angrily in a dark room with no escape.

The unsettling work preserves the real experience of Delfina Rodriguez, a maquiladora — or foreign-owned factory — worker from Tijuana, Mexico. After being accused of trying to organize a union, Rodriguez was locked in a room for 12 hours, a brutal yet common tactic used to force her resignation. For many women of Fusco’s generation, factory work once symbolized independence, but Fusco exposes how that promise masks exploitation. Multinational corporations — largely based in the United States and Europe — establish factories in border cities like Tijuana to profit from cheap labor and weak protections. The work draws attention to the persisting dominance of colonial power, suppressing worker organizing and rendering the Latin American labor expendable and unseen.

A large, golden cage stands in the center of the following gallery, borrowed from Fusco’s 1992-94 performance tour, “The Couple in a Cage: Two Amerindians Visit the West.” The live performance, which traveled to museums across Europe and the United States, staged Fusco and fellow artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña as fictitious “undiscovered natives” on display. Dressed in loud patterns, feathers and masks, the pair pose as Indigenous caricatures from the fictional island of Guatinaui.

As viewers enter the standalone cage, they step over a Mickey Mouse carpet to take a seat at a table with a British teapot and bottles of Inca Pisco, a Peruvian and Chilean liquor. A TV in the corner plays recordings of the 1990s tour, situating the viewer within the same space of observation. The captives are subjected not only to the gaze of outsiders but also to the imposition of imperial power in their daily routines. The diversity of objects inside the cage, from British tableware to Disney decor, highlights the reach of colonial influence on Indigenous life.

By placing herself inside the performance, Fusco dismantles false and dehumanizing portrayals of Indigenous identity. She draws on the troubling legacy of World’s Fairs and human zoos that once put Indigenous Latine people on display. What was once framed as education or entertainment is revealed as a demeaning spectacle designed to affirm colonial hierarchy.

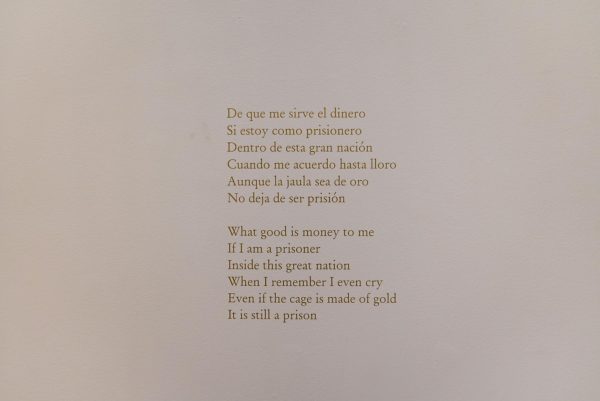

Beside the cage, a poem is painted on the wall in gold. Borrowed from “La Jaula de Oro,” a 1983 song by the Mexican norteño band Los Tigres del Norte, the song lyrics describe the pain of an immigrant who, despite achieving economic comfort in the United States, remains culturally lost. Fusco connects the immigrant experience to the enduring consequences of colonialism, expressing a subtle urgency: The cycle of colonization can’t be broken without first recognizing its limits.

Through depictions of entrapment, Fusco exposes the reach of European power across Latin America. Using performance, photography and art installations, she illustrates how colonial structures persist in new forms, from exploitative labor to global entertainment media. By satirizing outdated portrayals of Indigenous people and revealing long-suppressed acts of violence against Latin American communities, Fusco confronts the imperial forces — particularly those of the United States — that continue to silence them.

“Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island” is on view until Jan. 11 at El Museo and is free for NYU students.

Contact Siena Bergamo at [email protected].