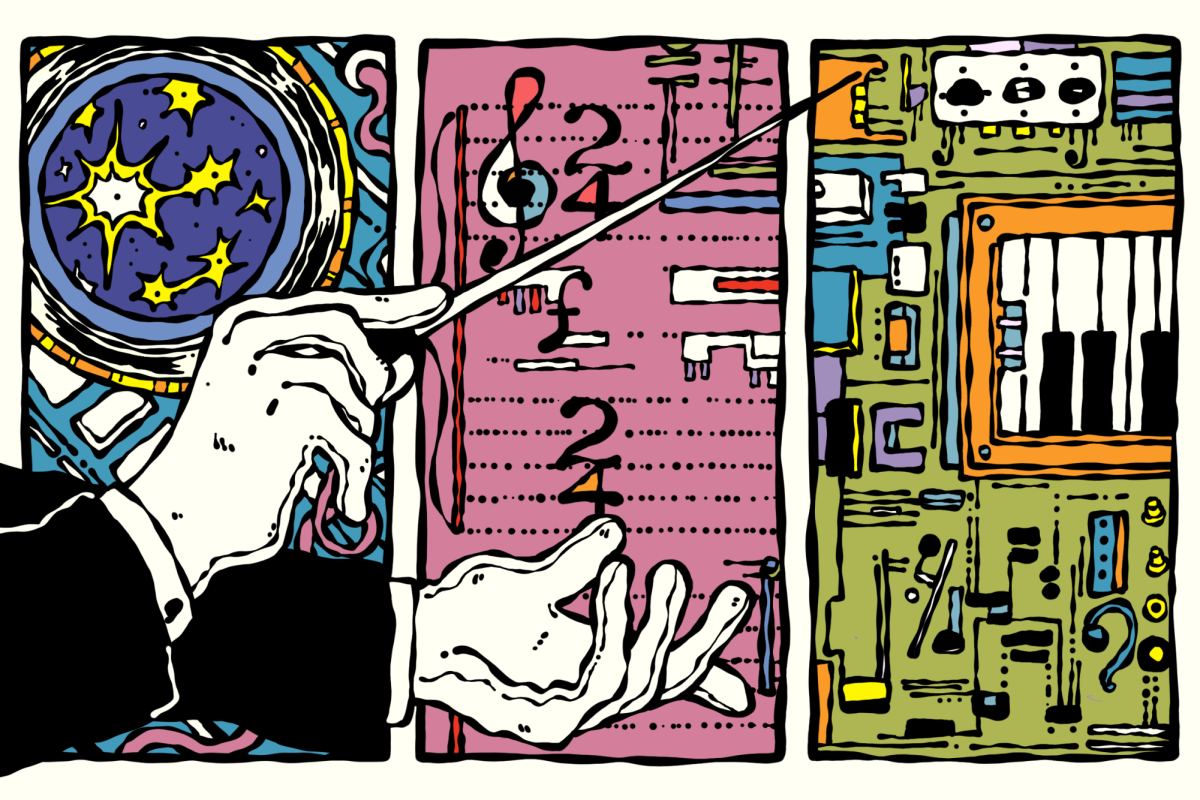

Review: ‘EO’ and a donkey’s odyssey across Europe

“EO” centers around a donkey’s experience in captivity, interactions with various sects of society, and eventual journey to liberation. “EO” is currently playing at Film Forum.

The latest film from Jerzy Skolimowski, “EO,” reflects on human nature by following the journey of a donkey. (Courtesy of FLC Press)

November 21, 2022

In acclaimed Polish filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowski’s latest film “EO,” a wandering donkey moves from one place to the next as the viewer bears witness to some of the darker elements of human nature. The film won the Cannes Jury Prize, and is now Poland’s official nomination for the Academy Awards. In America, the film was picked up by Janus Films, which successfully campaigned Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s “Drive My Car” to win Best International Feature last year.

“EO” subverts traditional cinematic conventions by filtering its entire runtime through the perspective of an animal. From abusive circus acts to intoxicated football hooligans, the donkey experiences countless trials and tribulations. In turn, the film delivers a gut-wrenching reflection on the state of modern humanity.

The lead donkey, known as EO, is originally part of a circus act with his affectionate owner Kasandra (Sandra Dryzmalska). In the heat of animal rights protests and a reactionary government shutdown of a Polish circus, EO finds himself ripped away from his caretaker and thrown into the fray of contemporary European society.

The donkey faces a journey of unexpected fortunes and immeasurable cruelty; he innocently observes the world through his many owners. Skolimowski was inspired to let a donkey helm his latest film after seeing one used in a Christmas nativity scene. Amid all the animals used in this Sicilian festival, the static donkey caught the director’s attention. He was transfixed by the idea that this motionless creature was an “observer from another world” and his eyes reflected a “mysterious comment on the scene around him.” The donkey is the stand-in for the audience in this film, yet the narrative is just as much about the treatment of animals as it is about the behavior of humans.

Although often seen as dull, the donkey is a cultural symbol that has taken us everywhere from Jerusalem to the Hundred Acre Woods. An unremarkable workhorse that has followed humanity through centuries of traumatic hardship, the donkey has always been a companion and observer of man. With this in mind, Skolimowski treats his four-legged protagonist with a heightened spiritual intimacy and respect.

The camera finds itself affixed to the disheveled textures of EO’s anatomy. Each strand of gray and white fur, his two pointed ears and his eyes capture the essence of this character. This is especially effective in the way Skolimowski uses extreme close-ups of the animal’s eyes to convey silent messages and reflections to the audience. Even the gaze of an animal has the power to touch the soul. Despite the lack of dialogue or an internal monologue from this character’s perspective, every frame of EO in the film makes us more enamored and attached.

EO examines the world for all its kindness, cruelty and sin. One moment he joins the electric festivities of a football game, basking in the limelight as an auspicious mascot. The same night, the opposing team — intoxicated and filled with juvenile rage — brutally assaults the donkey. He is maimed while shrouded in the darkness of night. Aside from this duality of collective pleasure and selfish rage, EO watches on as humans struggle to navigate their interpersonal relationships.

After being taken in by a young Italian gambler, he witnesses his new owner and his Countess mother — played by legendary French actor Isabelle Huppert — quarrel over family and wealth. In removing the human element from the narration, Skolimowski enhances the film’s objectivity by filtering his reflection on humanity through the naive eyes of a donkey. As these otherwise common and cliche scenes of ecstasy, love, greed and violence are refocused through a different narrative lens, their impact becomes all the more significant.

“EO” is a love letter to all animals and a treatise against their maltreatment. From the viewer’s perspective, the film gives agency and dignity to a creature that is often belittled and sidelined. The eyes of the donkey are also a way for audiences to reflect on the state of modern European society and humanity as a whole. This refreshing take on our desires and inhibitions as a species, liberated from a human perspective, accurately illustrates the often harsh and melancholic realities individuals have to face.

Contact Mick Gaw at [email protected].