Off the Radar: ‘The House That Jack Built’ attacks the cultural cult of the serial killer

Off the Radar is a weekly column surveying overlooked films available to students for free via NYU’s streaming partnerships. “The House That Jack Built” is available to stream on Kanopy.

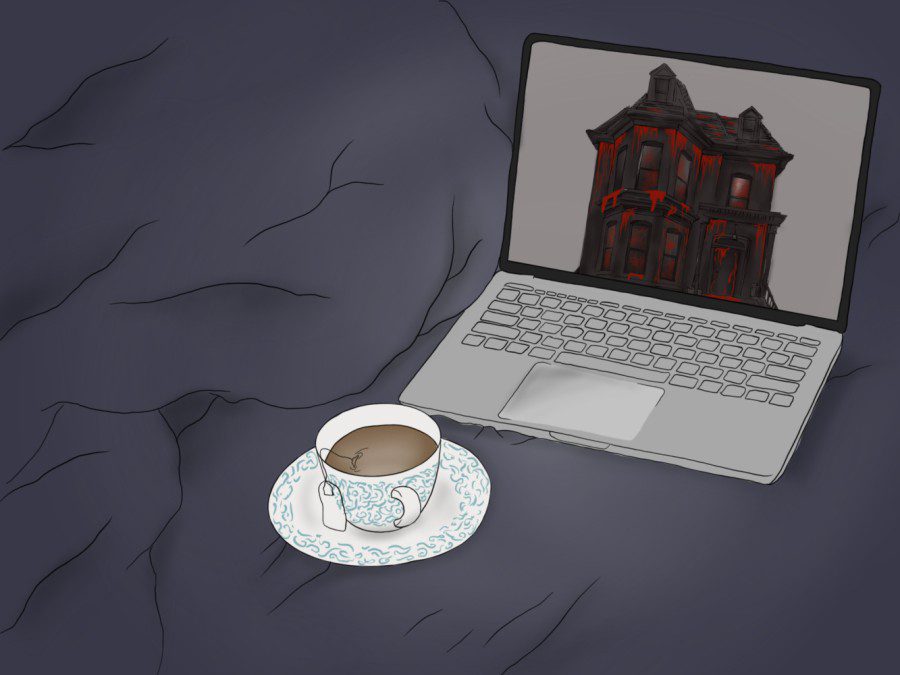

“The House That Jack Built” is available to stream on Kanopy. (Illustration by Aaliya Luthra)

October 28, 2022

A highly divisive film from a director that is no stranger to controversy, Lars von Trier’s “The House That Jack Built” (2018) uses the serial killer genre to delve into the impact and complex morality of violence in art. Critics labeled the film as “empty” and “repugnant.” Over 100 people walked out during its premiere at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. In the premiere’s aftermath, von Trier faced immediate criticism for glorifying violent acts, simplifying the killer’s psychology and excessively incorporating sadistic imagery. Despite the initial reception of the film, the film’s messaging and legacy are worth examining in light of today’s cultural fixation on serial killers.

The story opens with a black screen and a conversation between Jack (Matt Dillon) and Verge (Bruno Ganz). Jacks reveals himself to be a serial killer, boasting about the deaths of his five victims. Verge, a shorthand for Virgil, is Jack’s guide through Hell. While he accepts the diagnosis that he is indeed a sociopath, he tries to frame his actions — shown to the audience through interwoven flashback and montage sequences — as a pursuit for artistic greatness.

On the surface, the film illustrates the corruptive nature of obsession — how the aspiration to be memorable can manifest itself in dark forms. However, Jack’s musings about art, the artist and their legacy indicate that von Trier is specifically interested in his craft.

As an architect who has received a sizable inheritance from his parents, Jack dedicates his whole life to designing and redesigning a perfect house. Like many auteurs and craftsmen, he strives to leave a tangible mark of greatness on the world. Elegant pieces of classical music are interlaced through various points of the film, most significantly a piece played by famed pianist Glenn Gould who, in the eyes of Jack, is the embodiment of an artistic icon. Like Gould, Jack wants to achieve infamy and praise after death.

It is abundantly clear that Jack’s logic is both twisted and manipulative. His reverence for the likes of Hitler, Mao and Stalin as “artists” who have made an indelible imprint in cultural history only justify his motivation for murder. Even Verge, played by the man who is best known for his role as Hitler in “Downfall” (2004), shares the viewers’ frustration of Jack’s treatment of death. As his guide through eternal damnation, Verge sarcastically mocks and interrupts Jack’s endless rambling about art to remind him of the monster that he truly is.

While art may be subjective, the violence and trauma caused in the process is undeniable. As someone whose body of work is often scrutinized for having exploitative themes and visuals, von Trier acknowledges the power dynamics embedded in art. Especially with film, it is easy to place the viewer at a comfortable distance from the plot and characters at one moment then throw them into a vulnerable position the next. As consumers, we are reminded that to gain attention some pieces are designed to distastefully appeal to our shared voyeuristic urges. This has become evident in the recent surge of true crime docuseries and their respective dramatizations which consistently flash provocative content as a means of hooking viewers. Art can be iconic and beautiful, but it is also a manipulative construction.

Contact Mick Gaw at [email protected].