Review: ‘Fire of Love’ explores the visceral force of volcanoes and passion

“Fire of Love” is a fiery love story. The film will debut at the 2022 New Directors/New Films festival at Film at Lincoln Center on April 27.

Fire of Love. 2022. USA/Canada. Directed by Sara Dosa. Image courtesy National Geographic Documentary Films

April 25, 2022

Spoiler warning: This article includes spoilers for “Fire of Love.”

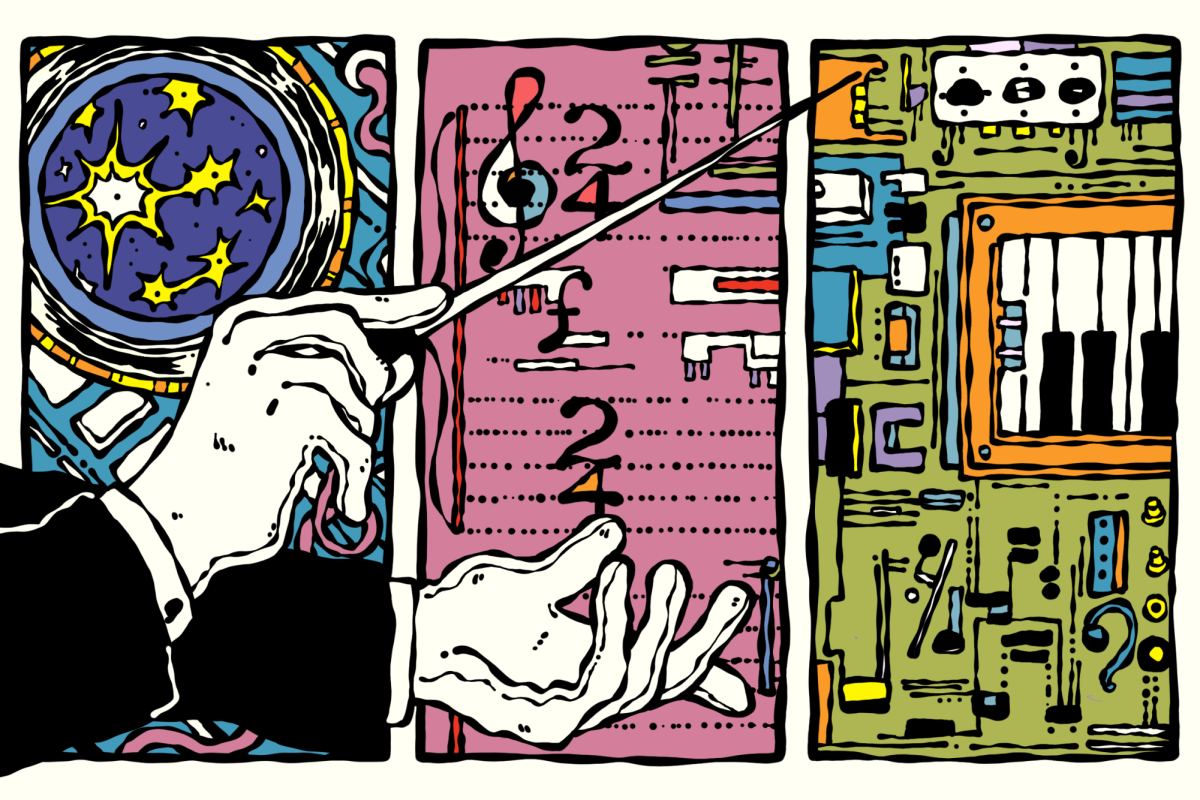

“Fire of Love” (2022), directed by Sara Dosa and screening at New Directors/New Films, tells the love story of two French volcanologists, Katia and Maurice Krafft, and their intense passion for volcanoes, almost as if the volcanoes were a third lover in their relationship.

This documentary consists primarily of archival footage like recordings of stippled volcanic rocks shot by Katia and Maurice themselves, originally with the intention of documenting what could be studied later. But little did they know that their footage would become a study of their blossoming relationship.

Katia and Maurice’s obsession with volcanoes becomes intoxicating over the course of the film. How could it not be when we’re standing with them at the heart of the action? We feel the rumbling of an approaching eruption, the clothes-singeing heat and the fiery streaks of volcanic explosions against the ashy plumes of smoke. Standing at the edge of craters, we see there is no sense of danger for the couple — they invite curiosity, not fear. The spectacle makes us question when Katia and Maurice will retreat from a rushing river of molten lava.

The film portrays an active conversation in humanity’s relationship to the earth. The couple follow the footsteps of the transcendentalists, fleeing to a sacred relationship with nature away from the dispiriting pitfalls of humanity.

“Fire of Love” is reminiscent of ecological themes in the other films that Dosa has directed, such as “The Last Season” (2014) and “Melting Ice” (2017). Politics also plays a role, as evidenced by Katia and Maurice’s stance against the U.S. invasion of Vietnam as young protesters. In a pithy declaration, one of them states that they got into volcanoes because they were disappointed in humanity. This, in turn, leads to a search for something larger than themselves, something beyond human understanding.

As we witness the external results of their work, the internal dynamics of the Kraffts’ relationship run on a parallel track. Their obsession marks them as weirdos to some of their colleagues; however, the two are misfits that need one another for their work. They’re like the tectonic plates that the volcanic eruptions so central to their life together — pushed together by irresistible forces, creating an explosive fit of passion.

There is an ephemeral quality to the archival footage that pieces the film together. It inherits a poetic nature, with brilliant cinematography that every so often leaves us questioning whether or not these shots were rehearsed. Oftentimes, we see the camera pointing at Katia or Maurice in a deep investigative trance.

Though Katia and Maurice are recluses from the rest of society in their everyday lives, their heart beats with the rest of humanity. Maurice says one of his dreams is for volcanoes to no longer kill people, a dream that inspires the couple’s efforts to emphasize the importance of evacuations and warn authorities about volcanoes’ mass destructive potential.

Dosa’s careful threading of the footage, interwoven with gossamer narration from Miranda July, composes together something reminiscent of Claude Monet, inking the screen with an impressionistic quality. The film adopts a riveting pace that juxtaposes July’s narration with eruptions that take command of the screen when she goes silent. Conscious retrospection allows the film to breathe while indulging in the visuals.

The visceral force of nature competes with the bond Katia and Maurice have. We see a dance between plumes of smoke whipping against the wind, a rush of emblazoned red rushing fast and, ultimately, the creation of new land. It’s as if they always knew how it would end: fiery, brutal, but at each other’s side. At the end of the day, the film is a love story — a love story between two volcanologists, the earth and humanity.

Contact Amira Aboudallah at [email protected].