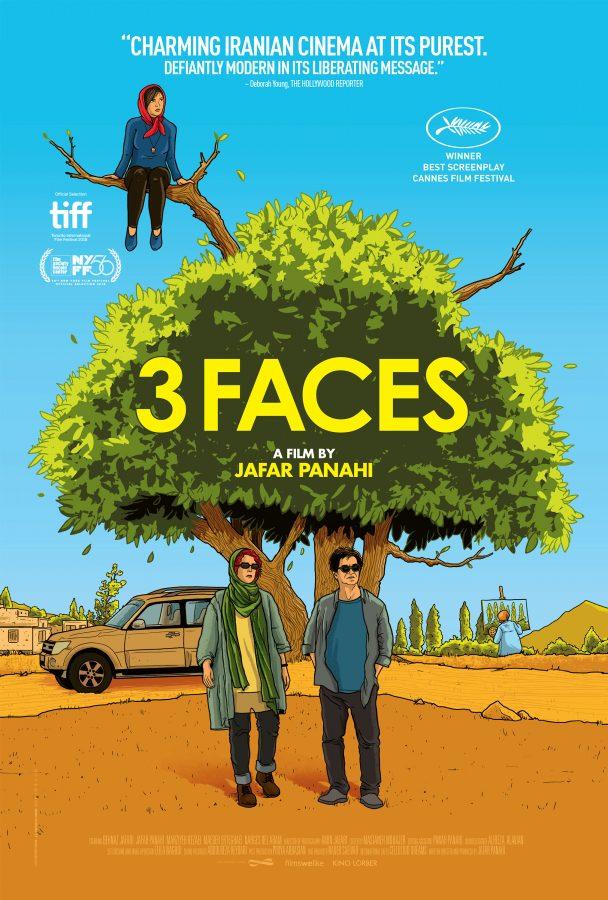

“3 Faces” begins with a girl’s iPhone confessional — her voice is shaking, as is her grip. Aspiring actress Marziyeh Rezaei (playing herself) has been accepted to the drama conservatory in Tehran, but finds herself nearly out of options after her parents betray her by refusing to let her go.

Everything about this sequence is desperate. In her video, Marziyeh pleads to Behnaz Jafari (playing herself), an already well-established Iranian actress, for help out of her troubling situation. Marziyeh then threatens to hang herself and, by all visual evidence, she does. She threads her head through a noose and her phone tumbles to the cave floor.

The suspected suicide weighs heavily on Jafari, so much so that she up and leaves her latest film project. With friend Jafar Panahi (playing himself) at the wheel, they travel to Marziyeh’s remote village in search of both the girl and an explanation, coming into conflict with dying traditions and strange characters along the way.

Marziyeh’s parents vehemently object to her pursuit of a career in the arts and want her instead to find a husband, settle down and raise a family. Such is the condition of many women in the Caucasus: not prevented from dreaming — Marziyeh’s mother even brought her to the conservatory audition — but steadfastly deflated if she were to ever get within reach of those dreams.

In hearing Marziyeh’s apparent last words, we as spectators are boxed into incrimination. A feeling of complicity washes over us. Director Jafar Panahi, by forcing us to bear witness, puts us right in the thick of the sociopolitical mess that causes women to take such devastating steps.

Dismal as the first few minutes are, the film that follows is surprisingly tender. In one scene, Jafari and Panahi come across a fallen bull on a road too narrow to hold more than one car at a time. Panahi suggests the herder euthanize it, to which the herder replies with an impassioned negative, on account of the bull’s strapping virility. “His testicles are miraculous … One night, he impregnated 10 cows!” Comical and endearing, yes, but also indicative of the deep-rooted masculine mindset from which Marziyeh is fighting to escape.

Marziyeh did not, in fact, kill herself. She staged her suicide to solicit help from Jafari. The actress finds Marziyeh, heart beating and physically intact, in a scene that culminates in a slap in the face of humorous proportion. Marziyeh made Jafari feel singularly responsible, and for that, the reaction was more or less deserved.

It was obviously wrong for Marziyeh to fake her death, but in another sense, it was the only action she felt matched her circumstance. For her and so many women, censorship is a fact of life, as is oppression, and the implicit shame associated with being an artist either prevents one from trying or reduces one to the simple rank of an entertainer.

“3 Faces” does not tiptoe around pervasive cultural stigmas, but makes them understood through positive and charming aspects of Iranian culture. It’s Jafar Panahi’s fourth film since fundamentalists in the Iranian government sentenced him to a 20-year filmmaking ban, but he continues to nudge cultural convention with his discreetly radical, humanist projects.

Email Elizabeth Crawford at [email protected].