Multilingual catcalling in Morocco’s medina

November 10, 2014

This article comes from the Global Desk, a collaboration between The Gazelle, WSN and On Century Avenue. Read more by searching ‘global.’ This is a personal essay.

RABAT, Morocco — Morocco is a linguistic rendezvous point, a place where vocabularies and vernaculars converge. You will hear French, Arabic, Tamazight, Spanish and even English, if you’re lucky. The newspapers are multilingual. The education is multilingual. The institutions are multilingual, and they hire multilingual employees.

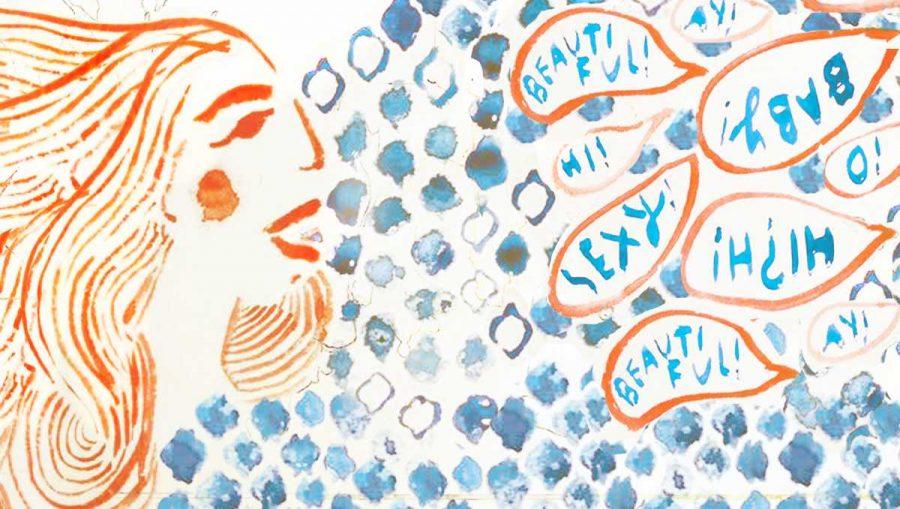

The sexual harassment is multilingual, too.

Hola, hello, bonjour, konichiwa. The Moroccan catcaller will fling out every possible dialect to grab your attention, rattling through greetings like a polyglot slot machine. Surprisingly, I find myself rarely reacting to this pestering with my typical angry response to catcalling. Maybe because this is not typical street harassment.

The catcalling in Morocco is not a menace; it is a spectrum. Attitudes range, cavorting between friendliness and curiosity, boredom and melodrama. There are proclamations of love. There are serenades and marriage proposals. There are inexplicable comparisons to famous pop stars — the number of times I have been called Shakira both baffles and excites me. It feels innocent and whimsical enough to make you laugh, until you realize what exactly you are laughing at.

On the September morning that I moved out of my Rabat homestay apartment had been a stressful one, I spent the early hours dragging myself and my oversized suitcase down three flights of stairs. My snubbed landlady lobbed judgement and snippy Arabic at me from above.

As I tromped through the medina alleyways, cursing my suitcase and packing hubris, I felt humiliated, gross and flustered. When I passed a group of teenage boys playing soccer in an alley, I steeled myself for the inevitable mockery. I looked ridiculous, bulldozing my giant luggage through the medina, struggling and sweating like some American tourist Sisyphus.

But as I blustered ahead, one of the boys trapped the soccer ball between his foot and the ground. “You are beautiful,” he quipped, smile slung across his face.

It cannot be reiterated enough how unbeautiful I had been in that moment.

That day I decked in baggy jeans and a men’s Radiohead tee. My frizzed hair had been interacting with the universe’s laws of physics in strange, spectacular ways. The sweat from my journey, sticky on my back, seemed to have turned into some special brand of T-shirt glue. Yet despite all these misgivings, I had just been called beautiful.

And, even though I claimed to hate catcalling — found it demeaning and upsetting — in that moment I felt amused, flattered even. It left me wondering. If I, who was so militantly against sexism, had actually been put in a better mood after being harassed on the street, what did that make me? A fair-weather feminist? A hypocrite? Human?

In Morocco, there is a racial tinge to street harassment, and it wears on you. When you find your ethnicity made into novelty, every konichiwa, ni-hao and shinwa is a barb. But I have felt more uncomfortable living in Abu Dhabi, where silent stares on the street turn you into a museum exhibit, a spectacle.

Navigating Abu Dhabi as a foreigner is made doubly difficult when you are a woman, because the most interesting spaces also happen to be the most male-dominated ones. Once, while reporting on Abu Dhabi’s fishermen, I enlisted a guy friend as an impromptu translator. Watching him swap jokes and back-pats with the male workers, I was surprised by the sudden, furious onslaught of resentment I felt. I expected to envy my friend’s language skills; instead, I walked away envying his anatomy.

Back in Morocco, I heading to the beach with some girlfriends when three men began to follow us. We employed all the stock tactics — resolutely ignoring them, saying no, quickening our pace — as they jeered and pestered. Eventually I exploded, turning around to half-yell, half-plead: “Enough, we just want to go to the beach, enough.” They only laughed at us.

Sitting unhappily on the sand moments later, I realized that this, here, was where the most infuriating aspect of street harassment lay. I had explicitly asked these men to be left alone, yet they took my protests as nothing more than mere suggestion, empty space. They continued to follow us, even though I had told them, begged them, not to.

To navigate a street dynamic that is constantly rendering you voiceless and agentless — it extends beyond annoyance. It digs deeper in ways that make you flinch, touching on broader cultural wounds like campus rape and sexual assault, suspect frat house drinks and an all-too-common mentality that swivels blame to the victim.

A world that disregards the importance of consent so flippantly is scary. It is sickening, and maybe that is why we rear away. Maybe we hate street harassment not only because it is annoying or demeaning, which it is, but also because for many of us this behavior is the dull echo, the subconscious throb, of every woman’s worst fear: being left unheard. Saying no, and realizing no one has bothered to listen.

Email Zoe Hu at [email protected].