International voters at NYU: How students from abroad view election season on campus

Under the Arch

International voters at NYU: How students from abroad view election season on campus

Students from nations electing their government’s leaders this year spoke with WSN about the culture of voting back home in the wake of the U.S. presidential election.

Aashna Miharia, News Editor | Oct. 28, 2024

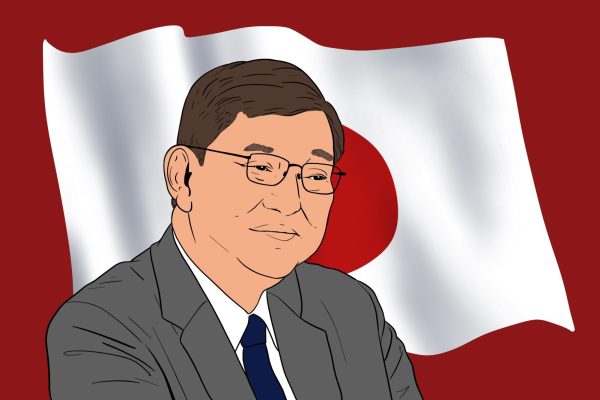

Throughout 2024, citizens from over 60 countries around the world took to the polls to cast their ballots in national elections. NYU harbors students from many of those nations, representing 133 countries total and priding itself as having the largest international student population of any higher education institution in the United States. This semester, international students at NYU’s Washington Square campus have observed much of their student body discuss the U.S. presidential election and gear up for Election Day — all while races for their own nation’s next leader are ongoing or recently took place.

Taiwan

Taiwan’s presidential election in January was historic and controversial in the eyes of CAS first-year Sean Hu, who grew up in the country. The elected Democratic Progressive Party candidate, Lai Ching-te — who advocates for policies to strengthen Taiwan’s allyship with the United States and defense against China — failed to earn over half of the votes. Meanwhile, the third party candidate Ko Wen-je, who created the Taiwan’s People Party, secured over 26% of the vote, the highest amount that a third party has amassed since 2000. Hu said that many young voters aligned with Ko because his campaign diverged from the major parties’ emphasis on Taiwan’s relationship with China.

“Right now is the time where the younger generations are more involved than ever,” Hu said. “Especially for younger people, the results are definitely hopeful because you can see that it’s no longer just two old parties competing with each other.”

While Hu was not eligible to vote in this year’s election in Taiwan — where the minimum voting age is 20 — he said that he has noticed more discussion around the election, including presidential rallies and debates, on NYU’s campus compared to what he observed at home during the Taiwanese election. Hu said he appreciated how American schools like NYU seem to openly embrace politics in classrooms, and that he wishes that was prioritized more in Taiwan’s education system.

Japan

Steinhardt sophomore Hinata Nakamura saw a similar contrast when reflecting on her community in Japan during the nation’s election for prime minister on Oct. 1. Nakamura explained that her social circle in Japan did not have strong views about the candidates because there were too many options — a record nine candidates ran to lead Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party, a victory which would subsequently elect them prime minister. Despite nationwide efforts to increase civic engagement in high schools, Nakamura said that youth voter turnout in Japan is drastically lower than overall voting rates.

“There’s an image that politics is not very fun or entertaining and there is a tendency in Japan to think, ‘My opinion is not going to matter,’” Nakamura told WSN. “There’s not a culture of speaking up in Japan.”

The elected prime minister, Shigeru Ishiba, campaigned for the government to alleviate the economic burden of Japan’s rising cost of living — which Nakamura said particularly resonated with young voters this election. He proposed allocating additional financial packages to low-income households and local governments, as well as raising the nation’s minimum wage.

Nakamura said that she did not cast her vote in the Japanese election, despite her eligibility, because it is a complicated process to vote while in the United States.

Indonesia

SPS sophomore Daffa Ariawan said that he waited in a line of thousands to cast his ballot for the next president of Indonesia while in New York City on Feb. 14 — the world’s greatest single day of elections. Ariawan said that many Gen Z voters did not support the winning candidate, Prabowo Subianto, because of alleged human rights violations. He said that young voters largely used social media to encourage people to vote and express their preference for policies that improve the quality of life in underdeveloped parts of Indonesia.

Ariawan said that at NYU, students are urged to vote and talk about the election more than in Indonesia, echoing Hu and Nakamura’s experiences in Taiwan and Japan. However, he said that with the political transparency in the United States comes a strikingly polarizing environment during the election season.

“In Indonesia, whoever you’re voting for, we’re just still vibing with each other no matter what — it also stems from the Indonesian values of always being there for each other,” Ariawan said. “But here, if you go to a party and you say that you’re on this side instead of that side, you can get publicly shamed. You can get shouted at.”

India

CAS junior Sujal Gandhi, like Nakamura, did not vote in India’s election for prime minister because he did not know of the resources available for voters overseas. During India’s general election this spring, Narendra Modi once again secured his position as the head of the government. His victory comes after winning a majority of seats in the Lok Sabha, the parliament’s lower house — but far less than he expected after a landslide victory in the 2019 election.

Gandhi also noticed the polarizing culture in the United States as an NYU student, saying that he does not feel that people back home are ostracized for holding different political beliefs nearly as much.

“Teachers or high-rank officials in schools are not as cautious of their opinions and how they can come across in India as much as they have to be in the U.S.,” Gandhi said. “From my experience, I’ve seen that a lot of things that have been said — a lot of jokes that have been made in India in front of me — could be seen as very problematic here. That just speaks to a lot about how involved people are in social issues and politics.”

Contact Aashna Miharia at [email protected].

Aashna Miharia is a sophomore studying journalism and public policy with a minor in business studies. She’s from the Boston area and is a novelist, Dunkin’...

Allina Xiao is a junior studying computer science at CAS. When she's not switching her third minor again, she can be found enjoying her fourth semester...