At the beginning of this year, Mayor Eric Adams and Gov. Kathy Hochul announced they would ramp up protections for New Yorkers riding the subway, expanding the MTA’s partnership with the New York City Police Department.

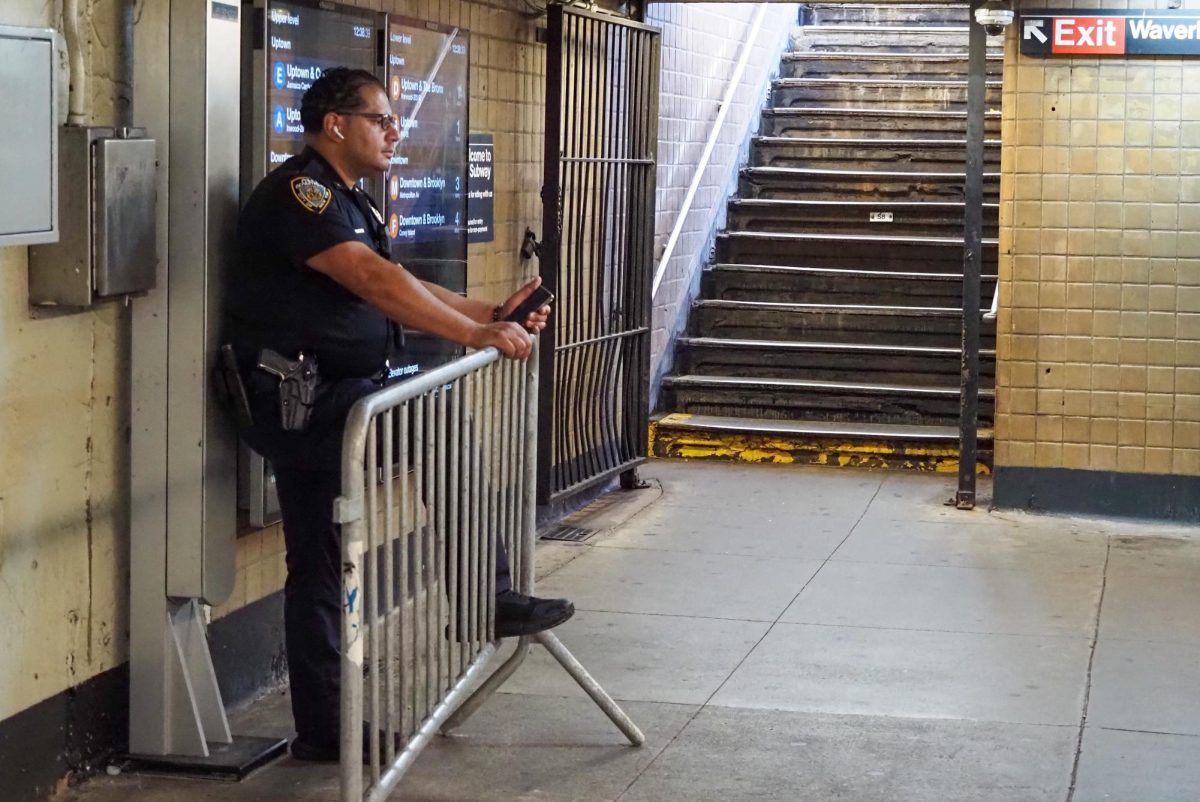

As a result of the initiative, 750 NYPD officers and 1,000 members of the National Guard are present at subway entrances and within stations across the city, with an additional 300 NYPD officers inside the train cars themselves. This militarization of the subway system, where over 3 million New Yorkers find themselves every day, is incredibly misguided and will likely yield more harm than good.

Specifically, the initiative will focus on the 30 stations that account for 50% of crime in the subway system, a statistic drawn from a 2025 report conducted by Vital City. However, the report cites a major, yet overlooked, caveat to this number. A majority of the stations deemed the most crime-ridden in Hochul’s initiative, such as 59th Street–Columbus Circle and Grand Central-42nd Street, are not actually the most dangerous — rather, because they’re transit hubs, these locations wind up being the most populated on a daily basis.

Hochul, in fact, explicitly expressed that the heightened National Guard presence was not in response to any specific or calculated trend in crime, but rather about “continuing a strategy.” The ambiguity of this statement furthers concern around the validity of militarizing subway stations, and raises questions about whether Hochul and Adams are prioritizing actual safety or merely the tough-on-crime illusion of it.

Hochul and Adams also advocate for strides to expand the number of Subway Co-Response Outreach Teams — also known as SCOUT teams — present within the system, a mental health initiative that pairs individual trained clinicians with a few police officers. In March, city officials announced $20 million would be allocated towards expanding SCOUT teams, as compared to the whopping $154 million cost of deployment for NYPD officers. However, and quite alarmingly, Hochul’s aim is to only have 10 SCOUT teams across the entire city by the end of 2025 — meaning that only 10 clinicians would actually be hired.

Each SCOUT team is only dispatched on a case-by-case basis, one individual at a time. On top of this, a SCOUT clinician confirmed that there is no standardized way for teams to operate, often leading to harmful, physical coercion used to transfer individuals to psychiatric facilities. Our city’s most vulnerable communities experiencing systematic mental illness and homelessness are being punitively treated in a way that likely exacerbates the issues they face, rather than being aided in a way that prioritizes community rehabilitation over individual correction.

While the idea of clinicians working with NYPD to handle crisis cases seems effective, the reality is that it is near impossible for a program like SCOUT, which requires intensive training and proper levels of sensitivity, to operate on the scale of New York City without more adequate funding and resources. The disproportionate amount of funding devoted to NYPD and National Guard presence should be in part reallocated to expanding SCOUT for a community-centered intervention that can serve more than just a few people at a time.

The Vital City report also concluded that, within the top 10% of individuals who have been arrested for subway crime, 90% have at some point experienced homelessness, pointing to a systemic root to the problem. In fact, most New Yorkers favor reducing homelessness and affordable housing initiatives as their top priorities in public policy. The 2022 “Welcome Center” initiative operates as a system of transitional housing facilities for individuals to opt into in order to move from public spaces to full time shelters. Unlike the policing initiative, this encourages individuals’ agency and promotes voluntary movement rather than forcible displacement.

In January, Hochul said that she would “work with the NYC Department of Homeless Services to expand” the Welcome Center model near end-of-line subway stations. What was notably absent, however, was any data or specific details on funding — such as that provided with the NYPD, National Guard and SCOUT initiatives — to outline how these centers will be supported.

When we talk about community safety, it is true that some presence of NYPD on the subway is inevitable, and that a portion of resources should be dedicated to dispatching them. However, when we see those resources spent on opening fire at someone evading a $2.90 fare, mandating random bag checks for subway entry or forcing spit hoods onto individuals in severe crisis, it raises a question of who is actually allowed to feel safe on the subway.

Instead of the National Guard, Welcome Centers and programs like SCOUT should be at the center of our conversations about subway safety. Not only because they have more potential to be truly effective, but also because they help to quiet the narrative that individuals experiencing homelessness or mental illness are the root of the problem rather than the criminal justice system. Fix the context, not the individual.

WSN’s Opinion section strives to publish ideas worth discussing. The views presented in the Opinion section are solely the views of the writer.

Contact Anjali Mehta at [email protected].