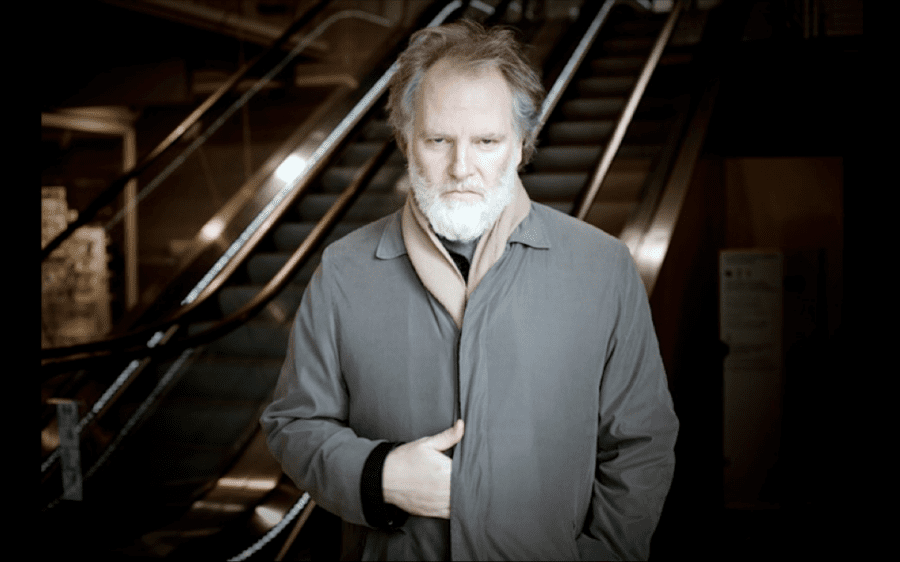

Q&A: Celebrated Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin talks myths and personality in filmmaking

WSN spoke with experimental filmmaker Guy Maddin about diary-filmmaking, Winnipeg and John Cheever’s self-lacerating writing.

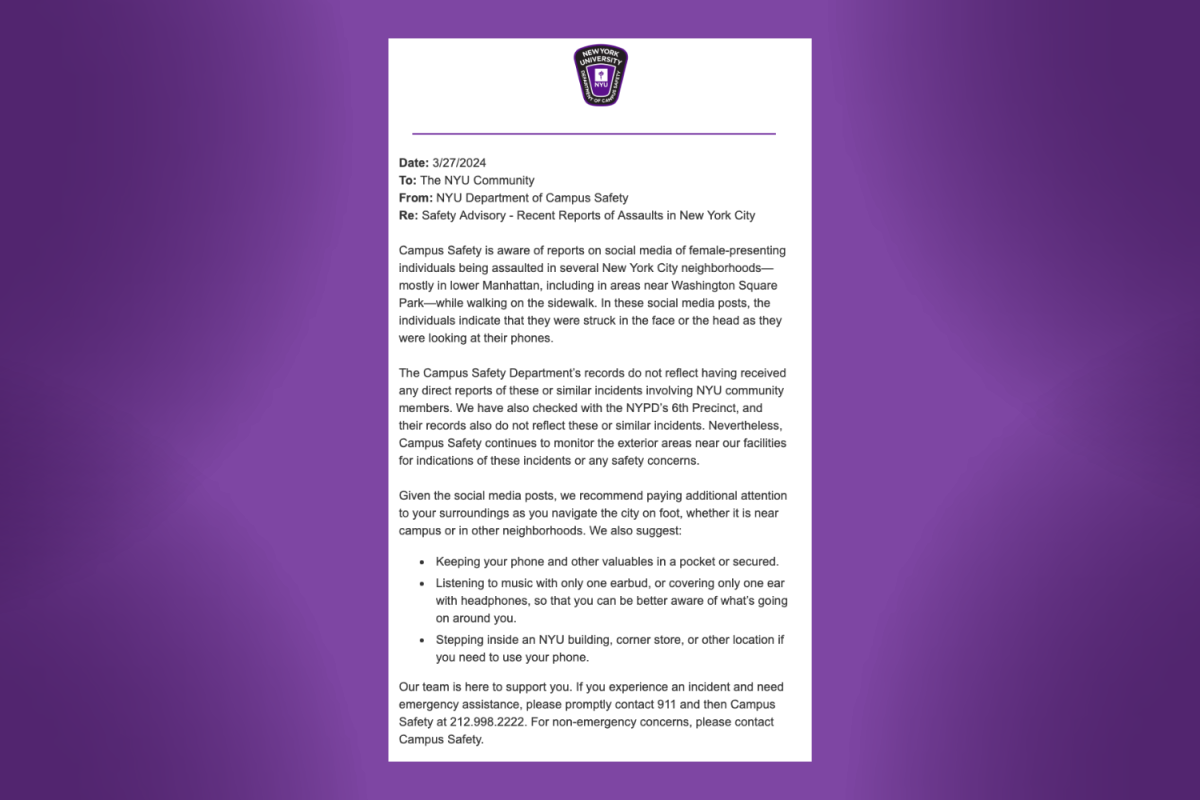

Courtesy: Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin stands at the Center Georges Pompidou in Paris. (Courtesy of Brian Geldin)

October 13, 2022

After 34 years of virtual invisibility, Canadian iconoclast Guy Maddin’s first feature film, “Tales from the Gimli Hospital,” has been restored in 4K and will receive a limited release at the IFC Center beginning on Friday, Oct. 14. The film will screen alongside Maddin’s celebrated short film, “The Heart of the World,” and the filmmaker will be present for two Q&A sessions on Friday, Oct. 14, which will be moderated by filmmaker Isabel Sandoval, and Saturday, Oct. 15, at 8:10 p.m.

[Read more: Review: ‘Tales from the Gimli Hospital (4K Redux)’ is the beginnings of contemporary cinema’s eccentrics]

Maddin, once described as “an aberration of modern cinema” by IndieWire, sat down with WSN to discuss the film’s re-release.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WSN: “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” was notoriously rejected from the Toronto International Film Festival when originally submitted, despite the fact that they had programmed your previous short film “The Dead Father” earlier in your career. How did it feel seeing this restored edition of your film finally play at TIFF?

Maddin: I’d like to say that I felt like I could really rub their noses in it, but the then-festival director, Piers Handling — who was on the selection committee back in 1988 when the film was first submitted — has since become a good friend. When he has had every one of my other pictures premiere at TIFF over the decades since, he has never failed to mention his embarrassment over turning the film down. Frankly, I think he went too far. Watching the film, you might see why it might get turned down.

I know Handling and his fellow selectors, based on information from an inside-plant on the selection committee 34 years ago, weren’t convinced any of the effects in the movie were intentional. And I’ve got to say they were only quasi-intentional. I learned that if I had any strengths at all, it was in considering whichever accidents I ran into when making the film I would consider happy accidents. That gave me things I could’ve never planned for, but the movie is pretty primitive.

I’ve become friends with Piers. He’s been very gracious, and though he’s since retired from TIFF, I noticed he was in the audience when it screened at the festival. It was pretty sweet. It wasn’t a big moment or triumph, but I have to say the film played OK. The film was always a challenge. People would always go out of some patriotic duty because it was always part of some Canadian programme, and it hadn’t found its audience back in the day. So, walk-outs were high — 50% or 80% of the audience. But now people knew what to expect, and there weren’t any walk-outs when it played a couple of weeks ago. That was a real thrill for me. It took 34 years, but it finally had the screening I dreamt of all along.

WSN: You mentioned this film coming together from a series of “happy accidents” when filming. Given this was an early work of yours, would you say those happy accidents informed your style moving forward?

Maddin: Yes, absolutely. I had never even picked up a camera before becoming a filmmaker. I’d made a short film before “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” and hired a cinematographer, but he was having some depression issues, and after doing a good job on the first day of shooting, he never showed up again. I was urged by a fellow filmmaker to be my own camera operator and responded “That’s ridiculous, I don’t know how to do that.” But I probably got so many more happy accidents by being an inept technician than my solid, professional, but depressed cinematographer would’ve given me.

I learned that I was primitive early on, and that put to mind watching my daughter, who was 4 years old at the time. She was at an age of genius, of sitting down with a piece of paper and a crayon and making something very quickly and primitively, but always so full of feeling and fun. I thought, “I’m going to follow my daughter’s methods and make a film full of feeling and fun.” Even though the feeling is dreadful, it’s going to be fun to depict it.

WSN: It’s interesting that you approach film very instinctually, and that so much of your aesthetic mirrors that of early cinema. Is there a connection there, that you and early cinema directors both approach the camera with wide-eyes?

Maddin: Yes, I think there’s something to that. Although it is a coincidence, it is also true that I approached the camera with the same wide-eyed naivete of a 4-year-old and decided to hold on to that carefree method moving forward. But I also realized that I hadn’t read a book on how to write a script. That might be obvious to people.

I hadn’t really taken any formal training at all, and I read up somewhere on the basic three-light set-up for film. But when I plugged my three lights in, all I got was three nose shadows on everybody. So I unplugged two of them and got something that, on black-and-white film stock, looked like German Expressionism; very dark shadows, a pool of light on the face of an actor that quickly graded off into mystery in the background, and suddenly I realized I was making images that looked like early cinema.

I played into that. “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” was the first film where I made it a period film. I knew I wouldn’t be able to master period filmmaking so well that I would fool people, but I could at least remind people of this stuff. Being unable to do the three-light set-up gave me a style, but it also helped me approach films the way silent films were put together. Silent films are a giant step closer toward fairy tales than talking-pictures, and I’d always made sense of my own life narrative in fairytale terms.

Whenever I read a book, I’d always consider it a fairytale first. At least as a way of drawing a doorway into a book and opening that door, getting inside and assessing whether it was more or less a fairytale. That was my entrance into art, into a book, into a movie, into a painting, into a poem or whatever.

Over the years, I got a little more sophisticated at figuring out what various pieces of art meant to me, but I found it very handy to enter art as an appreciator. And then as a maker-of-it, I just started with the sturdy timbers of fairytales and myths, and folk-tales and things. That went hand-in-hand with early cinema. It wasn’t like I set out with this clear-cut mandate to start film history over again and see where it went this time, but when that notion occurred to me, I thought, “Well, that’s not so bad, let’s see what happens this time.” Having said that, I made many of the failures that history did the first time.

WSN: That’s a very beautiful approach to art and memory. Throughout your career as a filmmaker based in Winnipeg, you’ve constantly mythologized your hometown, most explicitly in your memoir-film “My Winnipeg.” What has Winnipeg’s effect on you as an artist been?

Maddin: I’m in Winnipeg now and was in Gimli yesterday. I’ve been going there every weekend this summer. I’ve talked to a few artists who live around here, especially older artists like me who grew up in the pre-internet age just an hour away from the American border, but that’s a border with North Dakota so there’s really nothing on the other side. We were really far away from everything — I think an eight-hour drive from Minneapolis or something like that — so my take on what America was, was 100% mythology.

I’d never been there to see for myself what America was like, both as a child and as a young adult. But I had strong conceptions of what it was through the fabrications of Hollywood. I knew what LA felt like, I knew what New York felt like, I knew what Topeka, Kansas, felt like, and I knew what Kansas City felt like through little Hollywood myths, references to them in sitcoms and TV detective shows.

If I were to ever make something autobiographical, or to make some art up in Winnipeg, the greatest short-cut toward mythologizing this place — which seemed like a pet project of mine since it’s pretty easy for a Winnipeger to feel a little down on his hometown — would be to give it the old Hollywood treatment and build it up again through film emulsion, the preeminent mythologizing medium of the 20th century. I started by doing it with “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” and eventually moved on many years later to do it with “My Winnipeg.” I feel like my work is never done, there’s always something more to mythologize about a place.

WSN: You’ve certainly mythologized Winnipeg, but having made several films starring characters that share your name, as well as more explicitly autobiographical movies, you’ve effectively mythologized yourself as well. How do you go about tapping into your memory when developing a film?

Maddin: Well, my mom, who just died last year at 104. At that age, it’s not a tragedy. She was born in a little Icelandic-Canadian pioneer farm in 1916, but it might as well have been 1816 because of all their isolation. When she told a story about family history, she told it in the same broad strokes that Icelandic sagas are written in. She was not a person who read at all — it was just culturally natural to her. She lived in such grim situations, she lived in a local funeral parlor, that she had such a delightful way of describing grim tragedies and I wanted to keep that tone for “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” because it felt mythic.

There was a time after I’d made my third feature, this thing called “Careful,” when I felt tapped out. Then I suddenly realized, “No, my mother’s told me all these stories, I can just do family stories, and myself.” I started doing it really directly in 2002 with “Cowards Bend the Knee,” which is a movie based on my own life, and halfway through shooting, I decided to actually name the protagonist Guy Maddin. That gave me that extra dollop of hot sauce, that extra masochism. All of a sudden, I knew the point of compass from which to approach the film: making myself look terrible.

I was making myself look as cowardly as possible, as sniveling, as self-serving. I’d be willing to cut my leg off to avoid waking up because there was something about myself that I wasn’t impressed with. Strangely, making films, especially films about yourself, does fill you with ludicrous hubris at times, so I was always inflating and deflating myself. And I feel like that’s a good thing to do in a movie — to not take yourself seriously for more than a few seconds.

It felt good to confess things about myself and the work felt more literary all of a sudden. It reminded me of the experience of reading John Cheever’s “Journals,” which is a favorite book of mine. He is unbelievably self-lacerating, and I love his writing voice. He’s hard on himself and really frank. He had one of his kids edit his journals because he was nearing death, and he’s really hard on them even. He’s kind of a bastard, but it makes for such great reading.

As unlikely a source of inspiration as it may seem, Cheever is as important as anyone to me. I thought if I could approach these works where I’m the pretext for the plot with the same cruel detachment Cheever uses, I’d have a leg-up on other people making films about themselves. I’m sure some pity creeps in somewhere because it’s certainly my go-to state-of-mind when I’m not making a film. But I just felt like it was pretty important for my films to take the piss out of me, and I was hoping some viewers out there would identify with themselves. If not, at least cowardly, spineless behavior has been a staple of film comedy for a century.

WSN: Though specific, the nakedness of the heart in storytelling always seems to reveal universal truths audiences can identify with. In today’s world of homogenized mainstream media, embodied in the Marvel takeover of Hollywood, would you propose young filmmakers looking to develop a unique style take a deep dive into themselves when approaching art?

Maddin: I’m taking a year off right now to gamble whether I can get a project off the ground, but I’ve been teaching a diary filmmaking class at the University of Toronto over the last few years. I know there’s no shortage of selfies in the world, but a selfie is different from self-regard or introspection. I challenge students, through a series of weekly exercises, to start documenting their earliest childhood memories with their iPhones, so they can experience what happens when you transform something autobiographical into a piece of video, how fictionalized it instantly becomes, but how true it also feels to them.

Students are very shocked to find out how good and entertaining their films are when they are personally invested in them, and when they’re actually about something they care about. The class is very nurturing somehow, the asshole percentage just plummets in these classes, and I really love how supportive everybody is, even if one film isn’t as technically impressive as another. I’m the last person who is going to judge somebody’s technical prowess — it’s just a willingness to open up that matters.

Of course, I warn students at the beginning that if they’re uncomfortable opening up, to choose something else to talk about, but nobody’s really had any trouble and some people go really far. I know what to say to 18 and 20 year olds now making films because I’m in active dialogue with them teaching them. I encourage them to start making short diary films with their iPhone because it’s permission to use the first-person singular, but also because I want them to talk about the past.

Sometimes I force people to reenact a humiliating instance from their past, and that forces them to cast the reenactment, find props, find some light, find some music, some sound effects, force them to edit it and put it together. By the time they’ve done all this, their memory of the experience has been altered into this piece of fiction that’s also true. By the end, I feel they understand cinema more, and I also feel like everyone of their works, no matter how primitive or crummy to the outside observer, has got something honest in it. It’s really thrilling to me, and so “take my class” is my advice.

Contact Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer at [email protected].