Director & star of A24’s ‘Funny Pages’ talk comics, subversive mentors & trusting your voice

WSN spoke with director Owen Kline and actor Daniel Zolghadri about their recent raunchy comedy. “Funny Games” is currently playing at Film at Lincoln Center and is available for rent on video on demand.

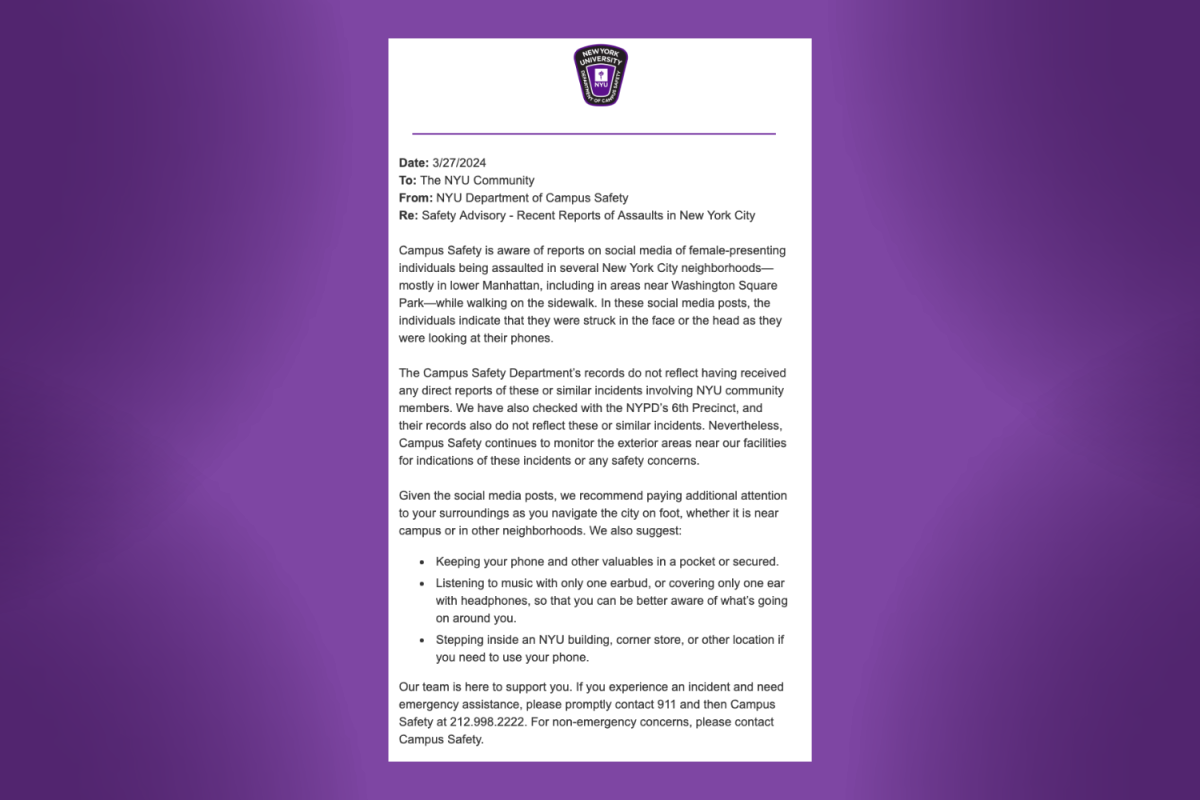

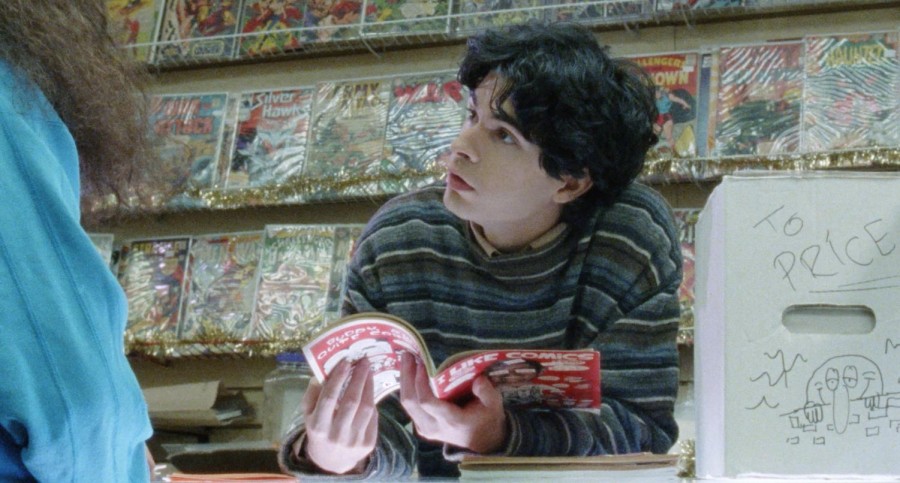

Daniel Zolghadri plays Robert in “Funny Pages”. The comedy “Funny Pages” is Owen Kline’s directorial debut. (Courtesy of A24)

September 1, 2022

Spoiler warning: This article includes spoilers for “Funny Pages.”

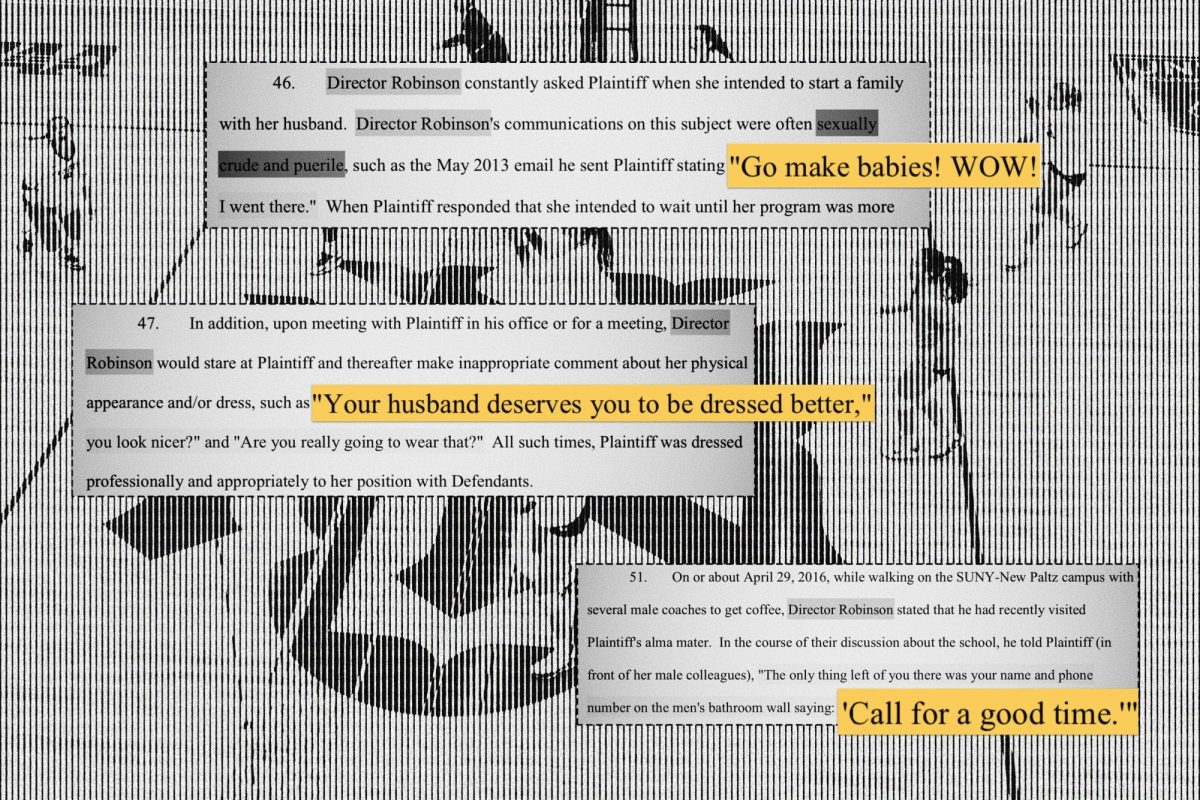

Several years in the making, Owen Kline’s directorial debut “Funny Pages” offers a laugh that’s been missing for quite some time in the contemporary world of sanitized R-rated comedies. Sharing more in common with films like Terry Zwigoff’s investigation into the life of cartoonist Robert Crumb and the daring forays into the ugliness of everyday life penned by the Safdie Brothers, Kline’s comedy about underground comics offers an uncomfortable amount of insight into the nooks and crannies of a rarely represented micro-culture.

The film follows young cartoonist Robert (Daniel Zolghadri) who decides to strike out on his own and abandon the comforts of suburban New Jersey to make it big as a graphic novelist. As Robert navigates a seedy labyrinth of unbridled passion, neurotic artists, awful apartments and teenage emotions, Kline extracts a coming-of-age story that teeters between gross humor and poignant lessons.

WSN sat down with Kline and Zolghadri to discuss the zany nature of “Funny Pages,” the film’s origins, and its deep ties to New York comic book culture.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WSN: Early on in the film, Robert’s teacher drills him about how he must subvert his medium to gain acclaim and become a successful artist. Do you consider yourself a subversive artist?

Owen Kline: I’ve always had subversive mentors in my life. I had a high school teacher who tried to get the most out of his creative students by forcing them to mine the very particular elements of their life they hadn’t seen represented in art, tap into those moments, figure them out, and treat their own perspective and point-of-view seriously in order to develop a voice.

I think that’s what Mr. Katano [Robert’s teacher] is trying to do when he’s looking through Robert’s bland figure drawings at the start of the movie. He’s trying to instill more than subversion — a point of view. Robert’s drawings come from an uninhibited place that is totally different from those of somebody sitting in an art studio in front of somebody naked trying to get the contours right. In those moments, there isn’t really much of a point of view that you can really imbue in a figure drawing, but I had a teacher in high school, the Creative Writing Teacher, who ran a comics club for the misfits and inspired us to develop our point of views. There was a lot of that in high school and then, working with the Safdies [“Good Time,” “Uncut Gems”] on this particular project, we realized we both ran toward the same wrongness.

WSN: Did that drive toward wrongness play into the technical elements of the film as well, including your decision to shoot on film and use plenty of close-ups to blow up the nitty-gritty, sweaty texture of faces?

Owen Kline: Yeah, even on a molecular level. If you’re looking at story beats, for example in that first scene, in the original version of the script hundreds of drafts ago, you never meet the teacher. You just hear about him. He’s already dead, and you find out about it later in the movie. But, it became apparent in examining the script that it could be a really strong catalyst for the story if we started out with that death. It sets the tone for the whole movie.

Previous versions of the script didn’t feel right. It was all about finding the right way to start the movie, setting the tone, and working with people who understood the impulsive and inappropriate qualities of the movie’s characters. The movie is a lot about the strange relationship between adults and kids, or young people coming into adulthood and having a weird view of it because of the adults around them.

WSN: With your main character, Robert, there appears to be a pseudo-independence where he anticipates adulthood and thinks he’s older than he is despite still being in high school. How did you, Daniel, as an actor, tap into that sense of anticipatory adulthood and navigate the strange world of adults set before you by Owen?

Daniel Zolghadri: At the time when we shot this, I really resonated with the part of Robert that really wants to strike out on his own and make something of himself. That part of him is really sure-headed and determined. Looking back, there’s something that I didn’t get about myself and the character, which are these self-destructive impulses like dropping out of high school, which now feels so wrong in retrospect.

Owen Kline: Every decision this character makes is wrong.

Daniel Zolghadri: Yeah, but at the time I was going through that too and hating school, thinking I would drop out too. There was this really passionate feeling that I, as a person, felt like this character was doing the right thing, and I viewed him in a heroic way. But now, I look back and realize he was just really making a mess of life.

Owen Kline: In relation to that thought, some of the earliest self-destructive urges that one has in high school — maybe I’m projecting — you don’t realize are self-destructive. You don’t realize what you’re doing to yourself a lot of the time. Sometimes it takes a movie or a therapist to orient you on what the fuck you’re doing.

Daniel Zolghadri: Now that I’m thinking back on it, I read the script completely wrong. It’s not at all what I thought it was.

Owen Kline: Well, I don’t think the character is wrong in his intentions. I think his intentions are completely valid. He wants to find his own way and his own voice, and he had a teacher that supported that, but he loses that guidance and ends up flailing around, going full kamikaze.

WSN: Something striking about this self-destructiveness is how it thwarts the characters’ artistic ambitions by enveloping them with a sense of insignificance. Like, toward the end of the film when the older graphic novelist is yelling at Robert and Miles, telling them none of them, himself included, are artists, there’s a real sense of self-doubt among the three that appears to be hindering the development of their practice. How do you push past this self-condemnation as an artist?

Owen Kline: Well, I think one of those real coming-of-age moments for me was having a lot of different artists from various disciplines that I looked up to, going to them for notes on what I’d written to try and improve it, and realizing everybody has a different way to slice an onion. Realizing that there is no objectivity in art — like William Goldman said famously, “Nobody knows anything” — is very liberating when it comes to finding your own voice because maybe Robert Crumb isn’t going to like some stupid song you recorded that isn’t a pre-war jazz number.

Daniel Zolghadri: Is that what happened?

Owen Kline: No. I’m just thinking of a hero and something I did in high school and Crumb might’ve not liked it, but this guy, say Johnny Ryan, who did all the fucked up drawings in the movie, might like it because everybody comes with their own baggage. When you get notes from somebody, that comes with its own baggage. The teacher at the beginning is just trying to inspire Robert. Later on, when Robert’s looking for a surrogate mentor, and he thinks that’s going to be this very ill man that he meets in the courthouse who turns out to be a bitter, broken casualty of the comics industry, he begins to realize he can’t keep mistrusting his voice by placing its judgment in others.

WSN: Well, it seems like this movie is working within a hermetic seal, this being the world of underground comics. How did you get into that world? Is there a permeating elitism within such a niche culture?

Owen Kline: I was very lucky to grow up in New York and do “Squid and the Whale” when I was a kid, and soon after that I was venturing into Brooklyn on the weekends. There was a comic book store called Rocketship and they had a mini comics rack for self-publishers, and I met my best friend that way who drew a little comic called “Afro-Bot” that’s featured in the movie. He was the only kid hanging around this comic bookstore and this was the only comic bookstore that I was aware of in the city with a focus on art comics and quote-unquote graphic novels.

WSN: Is it still around?

Owen Kline: Unfortunately it closed, but there’s a new store that opened up in the last ten or fifteen years called Desert Island. But, the predecessor to that was Rocketship. Both are great stores.

WSN: Being in touch with that world, did you find yourself pulling a lot of faces from it for the movie?

Owen Kline: Cartoonists are an interesting breed of artists, and you get an interesting, full gamut that I was certainly trying to tap into with this movie. It’s full of different people who draw, all with their own different styles. With the movie, there’s this classic, caricature-y device from old cartoons where a dog owner might look like the dog that I wanted to make apparent through the story, style and casting. Your signature comes through in the way you pace a story, whether you’re an amateur and you’re doing something sloppy or, opposedly, very obsessively and meticulously. A voice always comes through, and all these different artists who have all degrees of crudeness and sloppiness in them let that come out in the way they are, they act, maybe dress.

Daniel Zolghadri: I love “Afro-Bot” and in the movie, Robert doesn’t see that. He doesn’t see that in the imperfection of it. There’s a true voice.

Owen Kline: Even the juvenile influences that are ingrained in you and show themselves when you sit and draw come out in interesting, different ways that define you whether you’re an amateur or a seasoned professional.

WSN: A lot of the faces in the film look like they’ve been pulled straight from the pages of some of the authors you’ve mentioned — Robert Crumb, Peter Bagge, the list goes on. How did you go about gathering these actors?

Daniel Zolghadri: I just did the most boring casting process, which is just sending in a tape. Then I met Owen and it was all very standard.

WSN: I’m sure that audition tape will pop up in a future Criterion release as supplemental material.

Daniel Zolghadri: Oh God. I hope not.

WSN: Jumping to the end of the movie to that very pensive moment where you’re sitting at the comic bookshop’s counter after all the craziness that’s unfurled, what was going on through your head? What do you think was going on through Robert’s head as the credits begin to roll and you stand lost in thought?

Daniel Zolghadri: We thought about doing a moment where I was crying.

WSN: Like a “Call Me By Your Name” moment?

Daniel Zolghadri: I guess so, yeah.

Owen Kline: No, not at all.

Daniel Zolghadri: No, but that’s kind of what we were thinking, of doing a crying moment. Even in the script, in the initial script that I read which is way different than what the movie looks like now.

Owen Kline: And written way earlier than “Call Me By Your Name.”

Daniel Zolghadri: Right, anyhow, there was always that moment where it all sort of breaks out into a cry or something at the end. But we decided not to do that and we scrapped it. Then, there was one take where I was just laughing a lot, which I kind of like and miss.

Owen Kline: I was determined to make the very first movie where it ends with somebody crying. No, no, I’m just kidding.

Daniel Zolghadri: But the end result is just the best thing we could think of, to have Robert digest that moment and think.

Owen Kline: The movie opens with death, and the character has to digest everything that happened in the first five minutes of the film over the course of the entire movie. Then he has another incident, and another drawing lesson that puts his head in a tailspin, whether it’s a good one or a bad one, that’s up for debate, but he’s learned a lesson by the end which takes him back to that reflective space he’s in during the funeral at the top of the movie.

Contact Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer at [email protected].