The Role of Political Satire in the History of Film

October 5, 2017

As long as man has existed, there has been satire. And as long as there have been forms of government, as rudimentary as they have been, there has been political satire.

By definition, satire is for comedic effect, but effective political satire is capable of swaying society’s beliefs. Though satire does not provide a solution to political errors and woes, it does identify them. Making the public aware of systematic faults is the first step in learning how to address, and eventually attempt to resolve, these faults.

Political satire can be traced back to ancient Greece, where comedic playwright Aristophanes often criticized Athenian society through satire. According to Pennsylvania State University, even Ben Franklin had a reputation for his biting political satire. The genre has manifested in plays, skits, articles and cartoons, but perhaps finds its most potent ground in film.

Films that satirize politics often epitomize a certain era in time. A film about current political issues is unique to that time period and the current concerns of the people, serving as a kind of secondary source. Stanley Kubrick’s revered “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” is a prime example of a film rooted in the fears and anger of the people. Satire is a window into society, and when it coincides with politics, it is bound to portray a rather honest depiction of society.

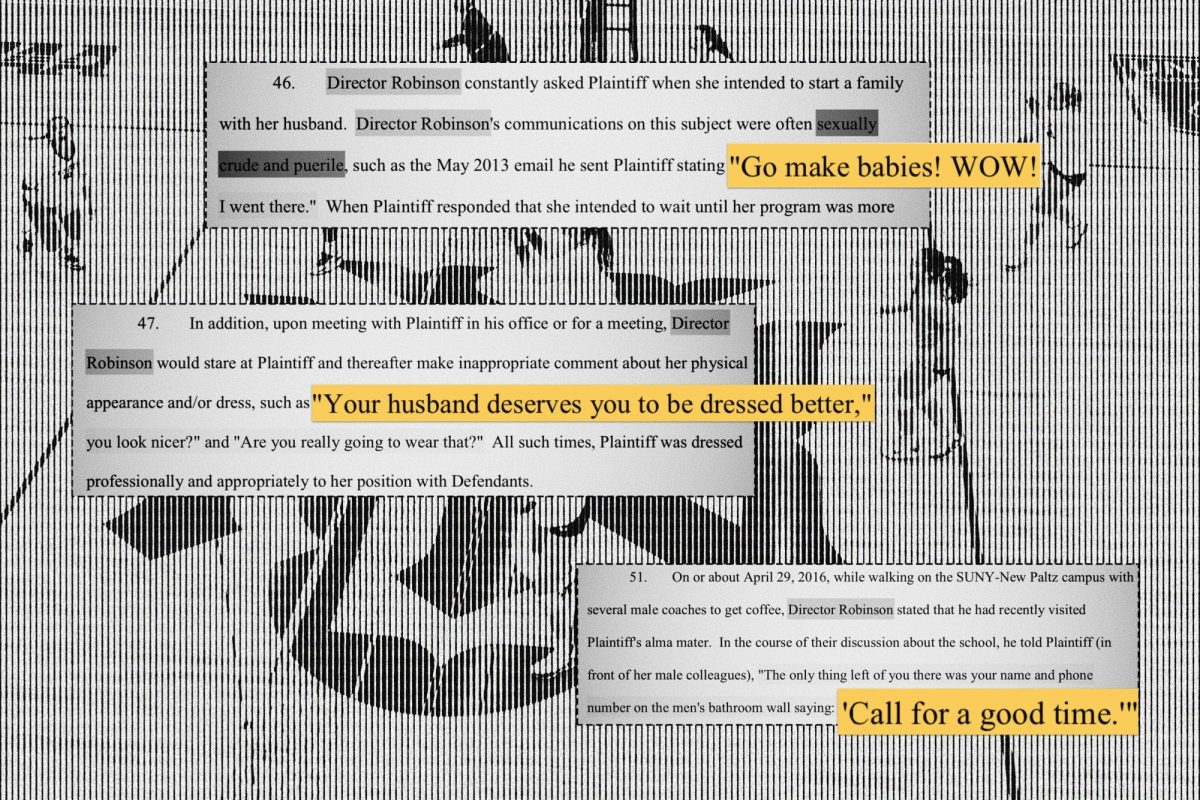

“Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” is steeped in the Cold War and is in direct response to the fear of global Armageddon by nuclear war. Kubrick’s 1964 film is one of the most famous example of political satire in film and rightly so. One of the most blatant themes in the movie is the comparison of militaristic power to machismo sexual prowess and lust. Missiles are suggestive of phalluses, and planes are personified in acts of intercourse. While humorous, Kubrick is really pointing at men in government who exploit their power for the sake of satisfying their extreme, primal masculinity.

“Dr. Strangelove” at first hints of nuclear destruction: the men abuse their power, sometimes without the proper authority. They act immaturely and impulsively, and it is fitting that the film ends suddenly in a mass nuclear explosion — the world erupting to the tune of “We’ll Meet Again” by Vera Lynn. Watching this film today, it is certainly within the bounds of reason to imagine a governmental figure pressing the wrong button at the wrong time.

The 1971 film “Bananas” is one of Woody Allen’s first movies, revolving around a New Yorker who chases his activist ex-girlfriend to the revolutionizing (and fictional) country San Marcos in Central America. Fielding Mellish (Allen), heartbroken after student activist Nancy (Louise Lasser, Allen’s second wife) leaves him for bigger and better things, follows her to San Marcos. In a surprising turn of events, Mellish is swept up in the revolution and is eventually elected president of the island by the rebels.

Mellish is wholly unqualified, which is reflected in his dictatorship, but he is far from the only source of incompetence. The rebel leader, who Mellish replaces as president, is ousted for his first decree — that includes the ruling that everyone must change their underwear every the half hour. And further, as the absurdity of the story develops, the news is parodied too, with one anchor reporting, “The United States government brings charges against Fielding Mellish as a subversive imposter, New York garbage men are striking for a better class of garbage and the National Rifle Association declares death a good thing.”

“Bananas” is a characteristically quirky film for Allen and reminiscent of the Cuban Revolution, echoing similar banana republics — small nations in Central America that rely on one crop. Though it belongs to that time period, its relevance can also be adapted to the present day. Some governments, and some governmental heads in particular, seem to blunder and blister in all affairs, domestic and international. “Bananas” calls out the incompetence of some politics and politicians to the wise laughter of the viewer.

Political satire in the arts is effective in spotting widespread flaws in systems of government and illustrating it to the public. Humor itself is powerful –– audiences may at first laugh, but then contemplate the gravity of what the movie criticized. Though satire has always had its place in society by holding leaders accountable through farce, in a world in which Saturday Night Live is having more and more difficulty making light of political situations, the genre is at its most formidable.

A version of this article appeared in the Thursday, Oct. 5 print edition. Email Jillian Harrington at [email protected].