How a string of student deaths in the early 2000s shaped NYU’s architecture, curriculum and mental health services.

March 7, 2022

March 7, 2022

(Photo by Kiran Komanduri)

Content warning: This article discusses suicide.

A student died in Bobst Library around 4:30 a.m. on Nov. 3, 2009. By 9 a.m., Bobst was already reopened, and no areas were cordoned off. By 10:54 a.m., the New York City Police Department had confirmed to Gothamist that the student had jumped from an upper floor.

John Sexton, the NYU president at the time, sent a universitywide email at 12:20 p.m. informing students of the death and encouraging them to contact the Wellness Exchange. At 12:22 p.m., campus tours for prospective students were still visiting the library.

Later that day, NYU admissions ambassador-in-training Natalie Veenhof told NYU Local that she had first learned about the death that morning when she arrived at Bobst to give a tour. Ambassadors are taught how to answer difficult questions from prospective students and their families, but she had not yet undergone the full training process.

Answering questions about suicide is now briefly discussed during the ambassador interview and training processes. Ambassador candidates participate in group interviews in which they answer questions they might receive from prospective parents and students during campus tours.

“One of the situations that an interviewee had to act out was being asked why there are bars in Bobst,” Steinhardt junior and former admissions ambassador Kate Carey said. “The person being interviewed had to talk about how there are mental health resources on campus and that NYU Wellness is really important to us, and that there had been a lot of work towards providing students the mental health resources they would need to be able to succeed under the stressful environment that university can be.”

Despite addressing this topic in the interview process, Carey said that guidance on answering questions about the connection between Bobst and student suicides is not included in the handbook distributed to ambassadors. Ambassadors-in-training do, however, briefly discuss Bobst and suicides again during training.

There have been at least 18 confirmed suicides by NYU students since 2003, six of which occured between 2003 and 2005. While resources have been made available for immediate, short-term care, many students say the university has not provided adequate mental health services.

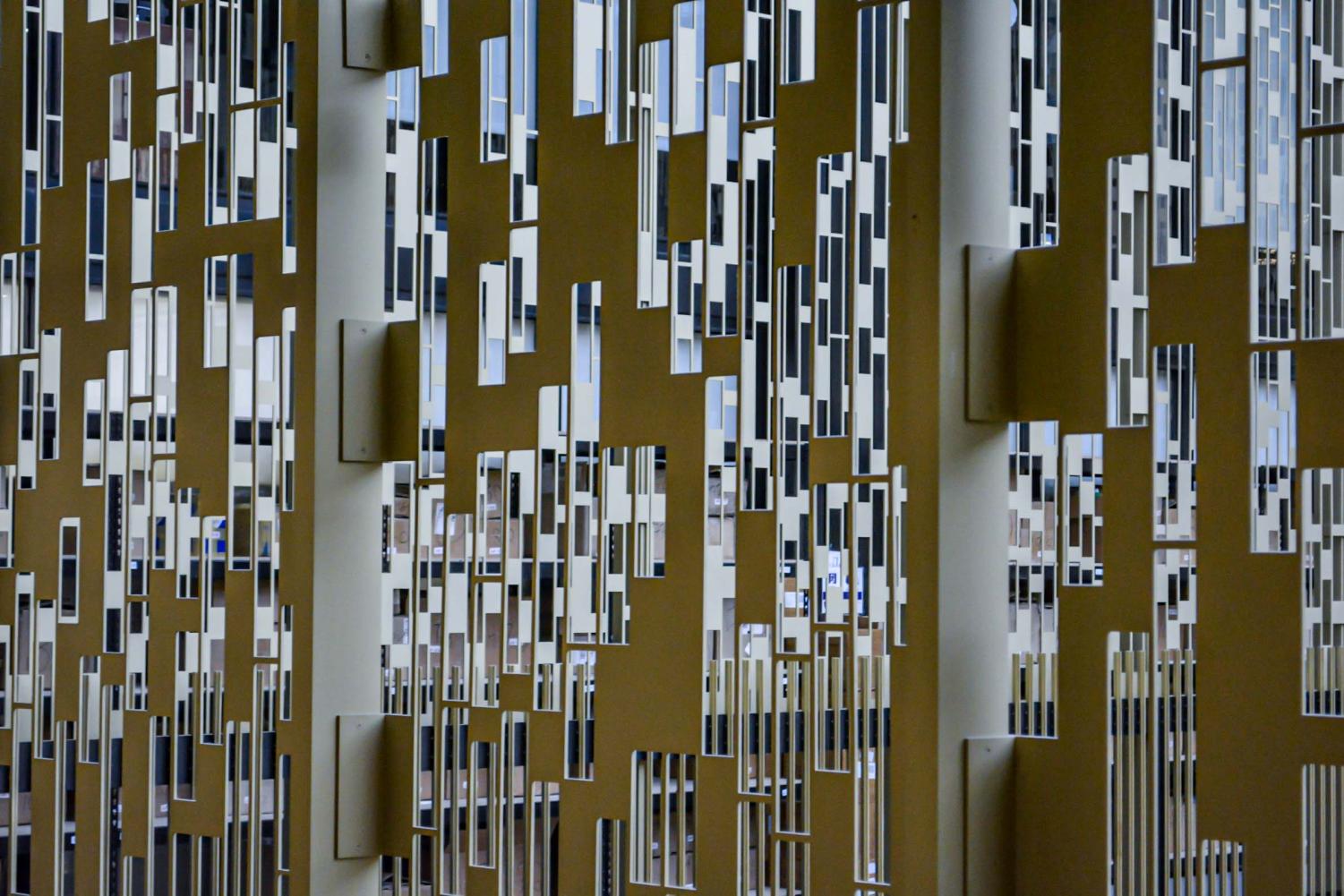

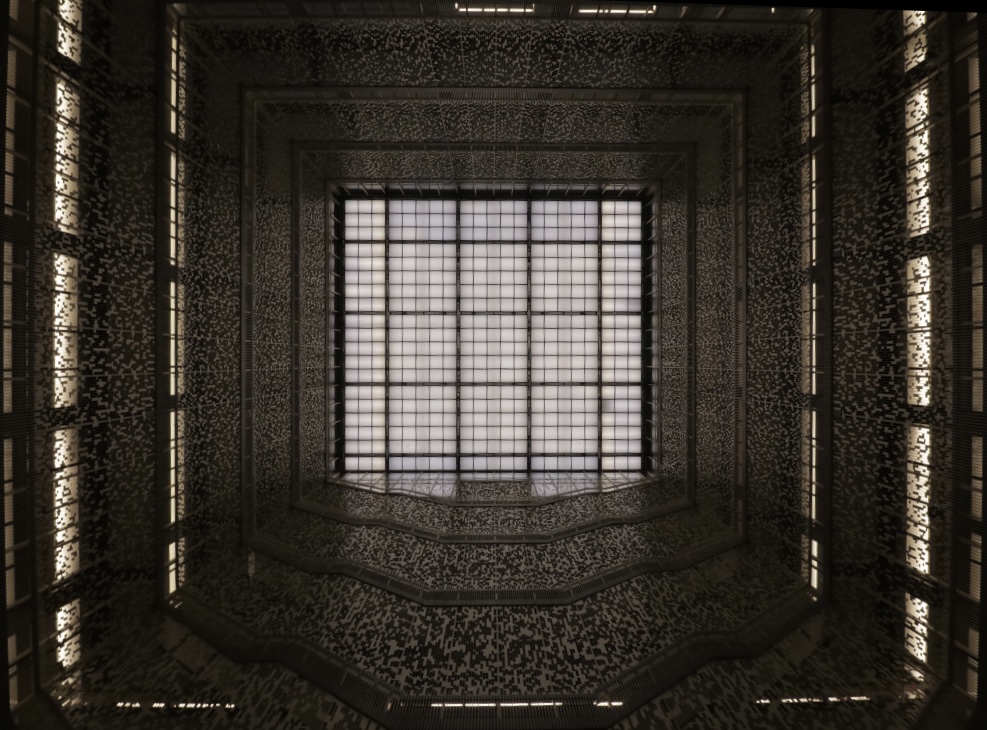

After seven student deaths between 2003 and 2004 — five of which were student suicides, and two of which involved students falling from the upper levels of the Bobst — the university implemented suicide-prevention measures, including restricting residence hall balcony access, developing the 24-hour Wellness Exchange hotline, hiring more mental health counselors, and installing 8-foot-high Plexiglas panels along the perimeter of the library atrium. In a 2003 interview with WSN, then-student Joe Savona said the panels seemed like an awkward, impermanent solution. They were replaced with permanent aluminum screens in 2012, but the installation was once again met with ambivalence by students. “It would be ideal to not have anything there, but it’s better than Plexiglas,” then-student Vincent Persaud told the New York Post.

The aluminum guardrails at Bobst Library were constructed as a permanent installation in 2012. (Staff Photo by Luca Richman)

After two students died by suicide in NYU dorms in 2007, the school took additional suicide-prevention measures, including installing locks on windows preventing them from opening more than a few inches. Despite some initial backlash from students, Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology, said that restricting access to possible jump sites is effective in preventing suicides.

According to the Harvard School of Public Health, 90% of individuals who survive suicide attempts will not die by suicide later; 70% of survivors will not attempt suicide again. If a person considering suicide is unable to access lethal means, their chance of initial and long-term survival drastically improves. However, physical barriers cannot always prevent suicide, as witnessed by the 2009 suicide of an NYU student who climbed over the Plexiglas panels in Bobst.

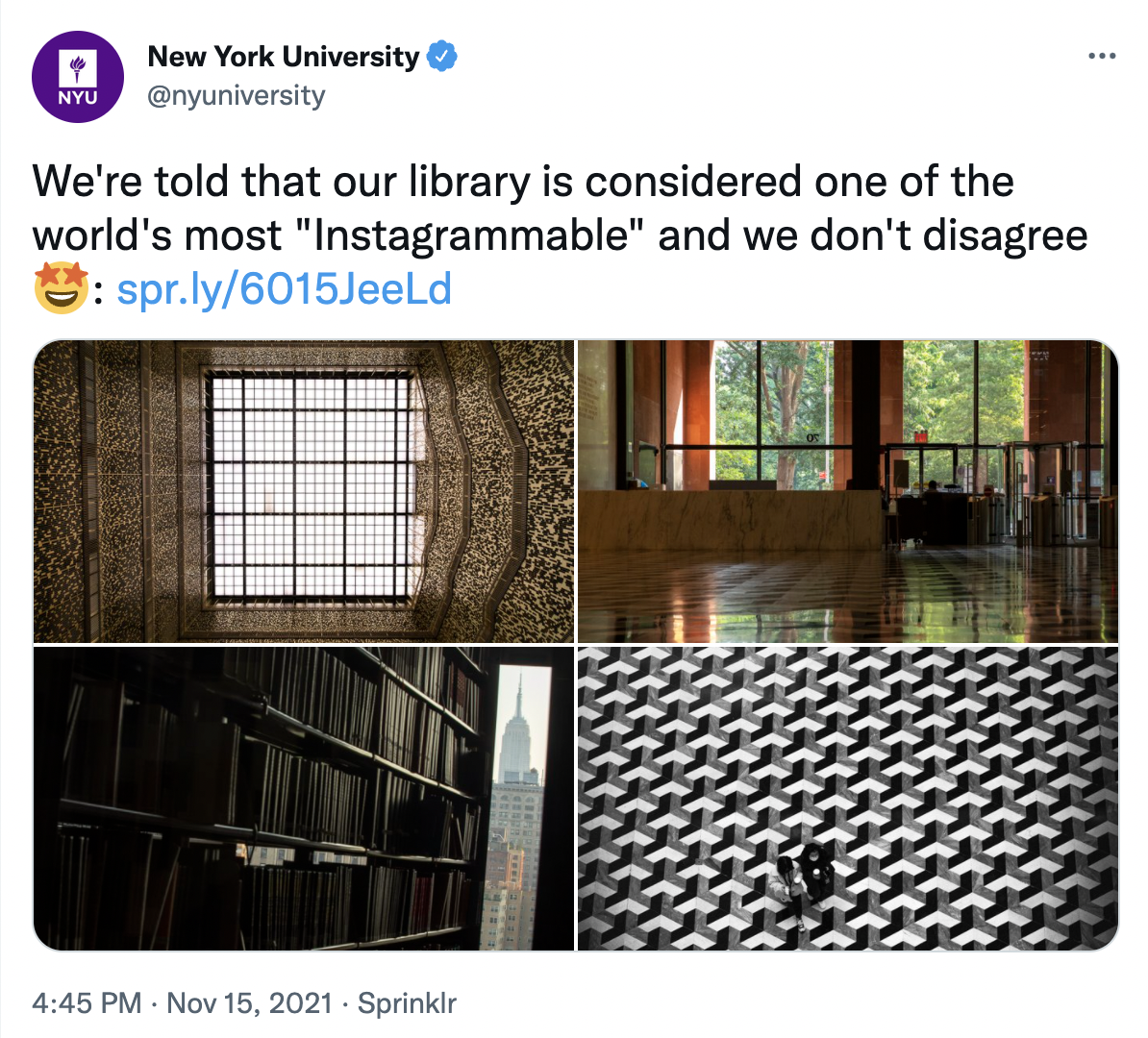

The current screens are often appreciated for their aesthetic form, while their original function of suicide prevention goes unnoticed. In November 2021, TimeOut reported that Bobst is one of the “most Instagrammable” libraries in New York City; NYU tweeted the TimeOut article with photos of the library’s lobby — without acknowledging, of course, why the installation went up in the first place. A handful of students noticed the omission, reacting to the university’s post.

The screens in Bobst are visually appealing to visitors who may be unfamiliar with their darker history — particularly prospective students and parents. The 2005 documentary “The NYU Suicides” suggests that the pattern of the atrium’s marble floor is an optical illusion “purposely designed to reduce suicide jumpers.”

The eerie ambience of Bobst lingers today. “When you walk in, you can cut the stress with a knife,” CAS senior Isha Ganguli said. “People are rushing around, sitting in the hallways doing their work. It’s always overcrowded, the lighting is not good. When I lived in a dorm and spent a lot of time in the library, I would often think to myself, ‘I kind of understand why they have [barriers] here now.’”

No student wants to think about suicide when they walk into Bobst. For those who know the library’s history, however, the guardrails serve as a constant reminder.

“Honestly, whenever I see it, I’m like, ‘Oh wow, that’s a super beautiful way to prevent people from killing themselves,’” Stern senior Matthew Noel said.

Despite the history of suicides at NYU, the university does not track suicides as of 2018, according to NYU spokesperson John Beckman, and communicates with the university community following student deaths on a case-by-case basis. Many universities are concerned about gaining a reputation as a “suicide school,” as it could discourage prospective students and parents.

“The Bobst architecture is the one factor of NYU that everyone knows, and they can never outrun the shadow of having so many suicides that they need this preventative architecture for students,” Ganguli said. “It was a little off-putting as a new student and someone visiting when I was like, ‘Oh, that’s what the school is known for.’”

An NYU spokesperson told WSN in 2013 that in many instances, family members of the deceased request that information remain private. In some cases, the university contacts students directly affected by the deceased’s passing. When news of a death spreads through the community — either by word of mouth or through news publications — NYU issues a universitywide statement to share crisis resources.

In response to a tragedy, NYU typically recommends contacting the Wellness Exchange. Following one of the 2004 student suicides, WSN published a Letter to the Editor from then-student Ellie Miller.

“Yet again there has been another suicide associated with NYU. Yet again we received a cursory email informing us of the incident and reminding us of campus resources,” Miller wrote. “The short emails and lack of discussion about suicide, mental health and the stresses on students — particularly transfer students and particularly those who transfer mid-year — are not enough.”

In the years following Miller’s letter, more suicides occurred on campus, but NYU’s response remained the same.

In 2018, when an NYU student died by suicide on the L train platform at the First Avenue station, the university did not communicate to students about the incident. Instead, most students found out through a New York Post article.

The student was pronounced dead at the scene at around noon on Oct. 2, but the incident was not addressed by the university until 1 p.m. on Oct. 4, when the Wellness Exchange eventually sent an email with the subject line, “Available to you 24 hours a day, every day.” The email did not mention the recent student suicide. This messaging epitomized how some students see NYU’s mental health services — prioritizing crisis intervention and neglecting to provide long-term support for ongoing mental health issues.

“They’re not really services,” Noel said. “I feel like NYU in particular loves to have things on paper so that they can cover their bases, but there’s too many kids here and not enough resources in terms of mental health.”

In fall 2020, Ganguli was experiencing problems with her roommates; she attempted to seek counseling services through NYU, but encountered long wait times and was not connected to a counselor until she said she was in a crisis. She originally felt supported by the services, but said that the counselor’s attentiveness eventually subsided.

“At first they’re really vigilant in booking you every 10 or so days, like, keeping up with you,” she said. “Then, as soon as the slightest thing changes and you’re doing a little bit better, the communication drops off and you don’t hear from them for a while, so then you lose interest.”

Similarly, Noel was directed to Counseling and Wellness Services after his athletic trainer found out he was grieving the death of a loved one.

“They couldn’t see me for like four weeks or a month, and then it’s just like ‘Well, I’m probably going to be fine by then. I’ll probably just work it out myself if I have to wait four weeks,’” Noel said.

Later on, he used drop-in counseling services under the impression that he would be connected to long-term care at NYU, but instead was directed to an outside provider. He chose not to pursue that path, and was not connected to long-term services.

“You’re meeting with someone who isn’t going to be working with you in the future, and then they’ll send you to some other unknown therapist in four weeks,” Noel said regarding drop-in counseling.

Despite the fact that college is a critical period for mental health treatment — 75% of mental health conditions present themselves before the age of 24 — many students struggle to access adequate mental health care at college. At the same time, universities struggle to provide that care because they are not designed to. They offer it because they have to.

“The complaints that students have about the limited access to the Student Health Center — that’s just ubiquitous,” said Jess Shatkin, a practicing psychiatrist and the founder and director of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Studies program at NYU. “That’s not good, that doesn’t excuse it at all, but they have limited resources. No college sees themselves as a mental health treatment facility, or even a physical health facility. They’re there for the urgencies.”

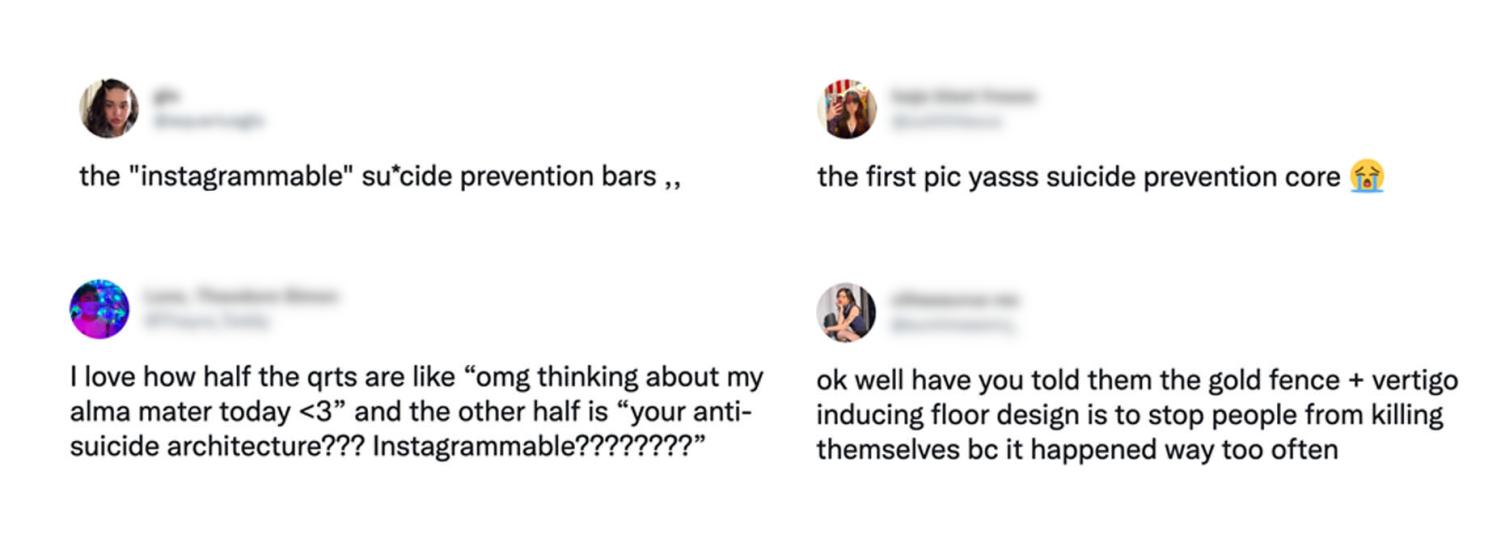

Dr. Jess Shatkin is the founder and director of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Studies program at NYU. The CAMS program is the nation’s largest undergraduate child development program. (Photo by Joshua Becker)

While NYU has taken measures to improve its mental health services — for example, removing the 10-session cap on long-term counseling in spring 2021 — counseling sessions are still being conducted virtually despite the shift back to in-person education. (WSN was unable to confirm at press time if the 10-session cap has since been reinstated; the SHC webpage currently suggests that students explore long-term care if they require “more than a few appointments.”) Virtual counseling is contingent on privacy — a privilege not every student has — and requires students to find a private space to conduct their sessions.

Ganguli was worried about her roommates overhearing her sessions. She was asked during her intake call if she had a safe space where she could attend counseling sessions. She said she did not, but was not provided alternative options for receiving care.

“I wasn’t able to explain to my therapist how bad things really were, because I didn’t want to be embarrassed. I didn’t want my roommates to be, like, ‘Oh, I heard you say this’ the next time I left my room,” Ganguli said. At times, she felt like she had to choose between attending therapy or being overheard by her roommates. On many days, she chose her privacy over the support she needed.

CAS sophomore James Scimeca started using NYU’s virtual counseling services last semester, attending each appointment from his apartment bedroom. During every session, he is worried that his roommates will hear what he discusses with his therapist, which occasionally prevents him from covering topics he would otherwise address.

“Sometimes I need to talk about things I don’t want my roommates to know about or hear out of context,” Scimeca said. “That’s been difficult since our walls don’t really mute any sound. Overall, the counseling experience has been beneficial, but it’s definitely affecting what I speak or don’t speak about, and how I approach subjects I could really use talking about.”

Both Scimeca and Ganguli said that having private spaces on campus for students to use during counseling sessions would make it easier to access mental health services. Ganguli added that the lack of in-person options for counseling is contradictory when less essential activities are allowed on campus.

“I think it’s just more convenient for the school to keep counseling services online,” she said. “I don’t think NYU cares about the students at all, honestly. It’s easier for the school, they save money and don’t have to deal with the logistics.”

The NYU Wellness Center is located at 726 Broadway. The center offers mental and physical health resources to all matriculated students and faculty. (Staff Photo by Camila Ceballos)

NYU reinstated fees on select Wellness Center visits on Jan. 4 of this year. An SHC provider said she was told to inform students of the change during December 2021 appointments; however, this information wasn’t publicized to students until after the end of the fall 2021 semester. In a Jan. 3 billing announcement, the SHC explained that emergency COVID-19 funding was used on Wellness Center visits to allow for continuity of patient care. While therapy remains free for students, NYU has resumed billing students’ insurance providers for in-person and virtual psychiatric services. Students are responsible for any charges not covered by their insurance plan.

The SHC is out-of-network for most insurance plans, so for students without school-sponsored insurance — especially low-income students — NYU has imposed a significant barrier to care.

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Studies program grew out of conversations between Harold Koplewicz, then-chair of the NYU Langone Child Study Center, and Matthew Santirocco, then-dean of the College of Arts & Science, following the suicides in 2003 and 2004. In the summer of 2005, Santirocco requested that the Child Study Center consider adding child and adolescent mental health courses to undergraduate course offerings. Although ideas had been in the works for years prior, program development only began in December 2005 when Shatkin was brought on to design a mental health education program.

Although the string of suicides pushed mental health discussions to the fore, the courses were not directly aimed at addressing suicide on campus. Shatkin worked with CAS, the Child Study Center, and the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development to build a seven-week, one-credit course covering stress management, organizational skills and other wellness-related topics. While teaching this class, Shatkin drafted a proposal for the CAMS minor. The program was approved in 2006, initially offering seven courses. As of spring 2022, more than 50 courses are offered as part of the cross-school minor.

There is not a specific CAMS class focused on suicide prevention, but the topic is discussed in other CAMS courses about mental illness and public health. This semester, 116 course sections were taught to nearly 7,000 students, making CAMS the nation’s largest undergraduate child development program. The CAMS minor inspired the development of CAMS on Campus at NYU, a club for students interested in mental health-related careers.

The most popular elective at NYU — with over 450 students enrolled on average per semester — is “The Science of Happiness,” a class in the CAMS program. The course is designed to reduce student stress and facilitate personal growth. (Staff Photo by Camila Ceballos)

According to Shatkin, one of the major points of contention in developing the CAMS program was the courses’ focus on self-help rather than academic content. “[The administration] was like, ‘Wait, we’re trying to teach them how to think and that’s our job. There are other places you learn about your health — that’s what the gym is for,’” Shatkin said.

The original idea — to create a rigorous wellness curriculum where students could learn both theoretical knowledge and practical skills — was implemented in “Road to Resilience,” Shatkin’s four-credit course that teaches students essential skills in anxiety, risk, and mood management to approach challenges they could face in college.

Simultaneously adjusting to college and New York City can be difficult for students at NYU. Navya Kumar, a CAS sophomore from New Delhi, India, completed her first semester online before moving to the city for the spring 2021 semester.

“As a stranger to the city, coming from India where everybody is so friendly and ready to help, I found it different over here,” Kumar said. “I expected more of a close-knit environment, but that’s not what New York is. And I know that now, but the adjustment period was tough. I felt overwhelmed a lot in the first couple of weeks for sure. I also tried NYU therapy, but it didn’t really go anywhere.”

Without a campus, it can be challenging for students to get involved in the university community and make real connections. “It’s not the easiest place — not that anywhere is an easy place — to be depressed, because you can be alone,” Shatkin said. “I think that’s one of the university’s fears — that you can find yourself alone sometimes without that definable place to sit in the grass.”

The impersonality of Manhattan and the competitiveness of NYU can overwhelm any new student. The anxiety and loneliness that follow can exacerbate existing mental health issues. Without a feeling of community, it is difficult to find support.

“The city could possibly be the loneliest place on Earth,” Noel said. “You’re literally walking by a bunch of people who don’t look you in the eye, don’t smile, don’t say anything to you. So if you’re in a sea of people who literally don’t care about you, you could feel way more lonely than even if you were on your own.”

The metallic screens in Bobst help prevent the most tragic consequences of these feelings. They show us where suicide prevention efforts should start — not where they should end.

“I don’t think that the solution should be to create a physical barrier that doesn’t allow them to kill themselves in your institution,” Noel said. “I think it should be to actually address the problem.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing thoughts of suicide, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. At NYU, contact the Wellness Exchange at 212-443-9999 or find a full list of resources available to you online.

(Photo by George Papazov)

Contact Alyssa Goldberg at [email protected].

Edited by Rachel Fadem. Developed for web by Arnav Binaykia.