The psychedelic revolution is coming. What is NYU’s role in this new age of mental health care?

Apr. 09, 2023

Apr. 09, 2023

In 2016, researchers at NYU published their first clinical study showing the positive effects of psilocybin, most commonly found in mushrooms, on treating depression and anxiety in cancer patients. As psychedelic treatment reenters the mainstream clinical sphere, NYU is pioneering the resurgence of research by getting involved in multiple dimensions of the field — hosting training initiatives, funding course development, engaging in advocacy for equitable access and leading legislative efforts.

Despite NYU’s prominent work in the advancement of psychedelic research, few students are aware of its position at the forefront of the revival. WSN conducted a series of interviews with employees at NYU Langone’s Center for Psychedelic Medicine to find out more about the university’s involvement.

NYU has joined the Heffter Institute, the University of California, Berkeley and Johns Hopkins University as a leading institution in psychedelic research, all playing a pivotal role in uncovering the clinical potential of psychedelics. At the CPM, NYU researchers have demonstrated the transformative power of plant medicines including MDMA — commonly known as ecstasy — and psilocybin to treat long-term mental illnesses such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, depression, alcohol use disorder, eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder.

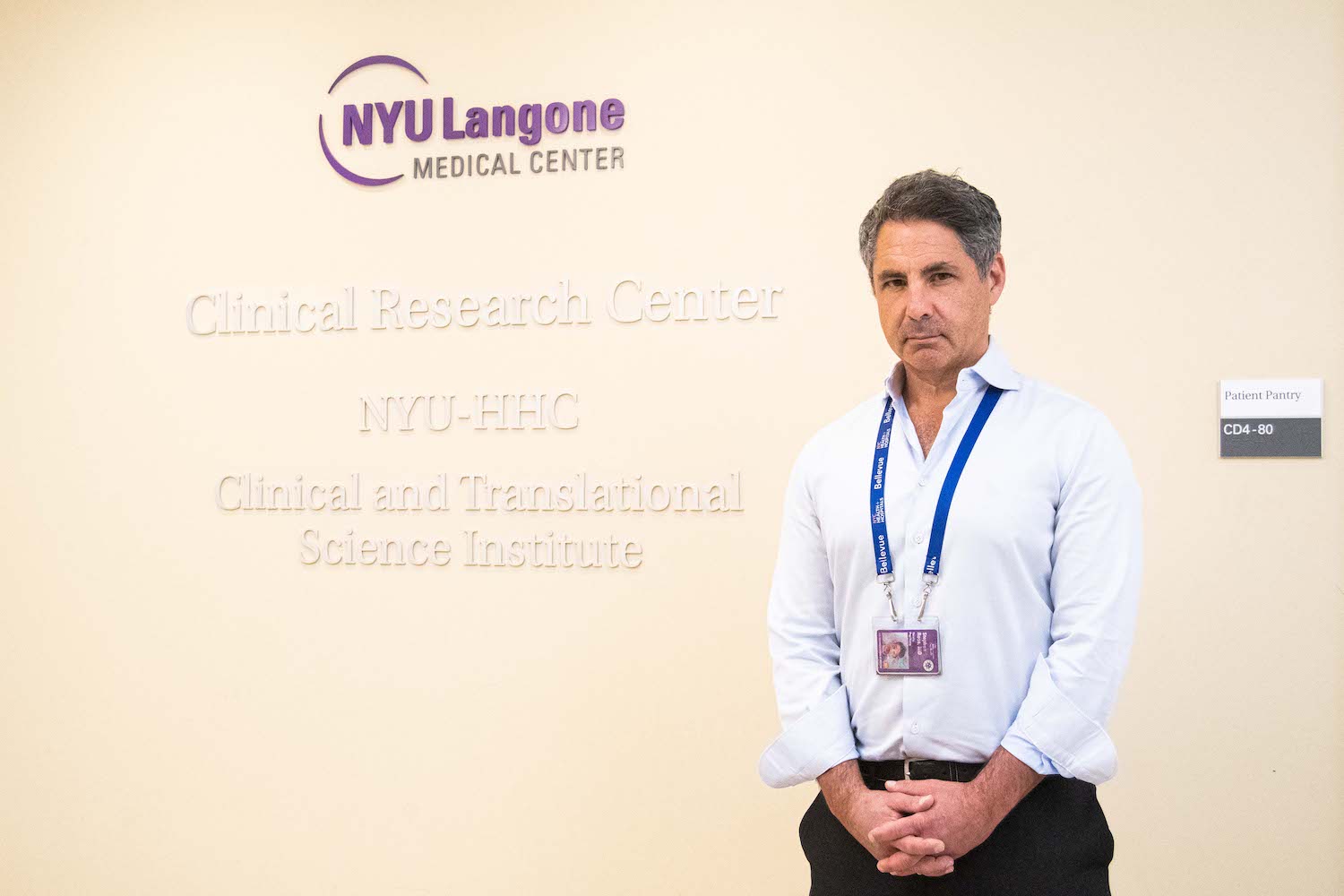

WSN interviewed three prominent figures at the CPM: Stephen Ross, the associate director and director of research training, Kelley O’Donnell, the director of clinical training and a psychedelic therapist, and Jon Kostas, the first study participant in NYU’s clinical trial on the treatment of alcohol use disorder with psilocybin.

Research into the clinical potential of psychedelics is not new. A fertile and promising period of psychedelic research in the ’50s and ’60s was prematurely abandoned and shut down, at least in part due to former president Richard Nixon’s war on drugs. Psychedelics, however, long predate their history in the United States. Spearheading a new generation of studies, the CPM is reinventing the perception of these drugs, moving psychedelics beyond the historical confines of stigma and criminalization. Stephen Ross, the CPM’s associate director, recalled the popular image of psychedelics after Nixon’s anti-drug crusade.

“Before any of that research could move forward, the drugs escaped the lab, got caught up in the counterculture movement, and, in 1971, Richard Nixon declared the war on drugs,” Ross said. “It effectively banished the whole era — I mean wiped it out from the history books so much that I never learned about it.”

Ross, now 52, is optimistic about the prospect of reshaping public perception with modern psychedelic research.

“During the first wave of psychedelic research, there was this whole ‘hype’ component, as if this was a wonder drug that was going to cure everything,” Ross said. “Then it became a demon drug and it was banned. I think we’re now in the ‘hype’ phase again.”

The psychedelic renaissance, a movement which has become increasingly relevant, refers to a new wave of research that promotes what has been described as a “paradigm shifter” for psychiatry, uncovering the therapeutic benefit of these illicit substances. In addition to introducing new approaches to mental health care, experts suggest that the use of these medicines could help promote new modes of inquiry and help us address imminent social and political issues.

“An even bigger question is whether psychedelics might help us address the environmental crisis and how we think about our place in nature,” said journalist Michael Pollan in a 2022 docuseries based on his book, titled “How to Change Your Mind.”

Although researchers are optimistic about the clinical benefit of psychedelics, they remain cautious of promoting psychedelics as a universal cure. In an interview, Ross emphasized the harmful potential of psychedelics, cautioning against their recreational use.

“It’s not true that psychedelics can cure everything, and we do not want to give students that impression,” Ross said. “There is a lot more work to be done to determine their safety profile. They can have enormous benefit, but, when used in the wrong context, they can have real harm.”

Psychedelics have a spiritual history, and clinical trial participants frequently recall encountering “the divine” during their psychedelic experiences. In response to the increased level of spiritualism in their practices, care practitioners are contending with these new approaches to psychotherapy.

The transformative impact of psychedelics applies not only on an individual level, but on a societal level too. By directly confronting a popular notion in Western psychology that considers secularism and professionalism to be synonymous, the legitimization of psychedelics within the clinical sphere may sequentially broaden the scope of treatment.

Psychedelics trigger a non-ordinary mental state, the experience often described as an expansion of consciousness. Over the years, the language used to describe these drugs has changed, reflecting a shift in public opinion. The original term, coined during the 1950s, was psychotomimetics, meaning “mimicking psychosis,” which served to deter people from use. Psychedelics is a relatively new term, though it has now been in use for decades, and joins roots meaning “mind” or “spirit” with “revealing,” indicating a new paradigm of understanding.

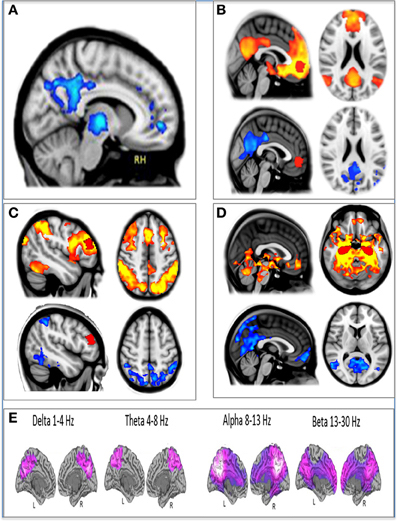

Psychedelics primarily affect what is called the default mode network in the brain, which houses the ego. In a brain imaging study published in 2014 on the effect of psilocybin, Robin Carhart-Harris, who leads the psychedelic research center at Imperial College London, found neurological evidence to support the mind-revealing effects of psychedelics. By decreasing activity in the default mode network, psychedelics break down the sense of self, as well as the stories one constructs about the self.

In an interview for “How to Change Your Mind,” Carhart-Harris highlighted the unique relationship between psychedelics and mental illness, conceptualizing mental illnesses as defensive reactions to uncertainty. “The psychedelic is really pushing against that defense mechanism, saying, ‘let go of that maladaptive strategy,’” Carhart-Harris said. “Because it’s not really serving you.”

Stephen Ross was a founding member of the Psychedelic Research Group at NYU and is a current associate director of the CPM. According to Ross, the CPM began in 2006 as a reading group at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, after the commemoration of the 100th birthday of Albert Hofmann, the chemist who first synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide, a synthetic psychedelic commonly known as LSD.

“I started looking to see why my colleagues were celebrating, and hidden within plain sight was a huge body of research in my own field of study from the first wave of psychedelic research in the ’50s and ’60s,” Ross told WSN.

As interest in psychedelics research rekindled, the group received a small grant from the Heffter Institute, a nonprofit funding psilocybin research, and published its first clinical trial in 2016. Ross credits this trial, along with Michael Pollan’s book and a trial at Johns Hopkins, for reviving psychedelic research. Upon receiving a $10 million philanthropic gift, the CPM was officially established in 2021.

The center is experimenting with the therapeutic effect of multiple psychedelics. It aims to treat existential distress, major depression, and alcohol use disorder with psilocybin, and post-traumatic stress disorder with MDMA. The center is currently preparing for their first LSD study for existential distress from advanced cancer.

Kelley O’Donnell is a psychiatrist, an assistant professor at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and the director of clinical training at the CPM. In addition to her research with NYU, O’Donnell owns a private practice that currently offers ketamine-assisted therapy, a treatment combining conventional psychotherapy and psychedelic medication. Distinguishing it from standard forms of psychotherapy, which follow a linear trajectory, O’Donnell detailed the psychedelic therapeutic model that has been used at NYU, and in the research context so far, which is centered around dosing sessions.

“Psychedelic-assisted therapy is certainly very different from standard psychotherapy. Whether we are working with MDMA or psilocybin, we are usually blocking out eight hours,” O’Donnell described. “In all the research studies so far, the participant has the option of sitting or lying down on a bed, and there is music playing in the room and headphones that they can choose to use, and there are eye shades that they can choose to use.”

Before the dosing sessions, there is a series of preparation sessions to build trust between the therapist and patient. O’Donnell emphasized that these preparatory sessions are fundamental to the healing process.

“There is a much higher risk associated with a psychedelic experience when it is taking place in a setting where that trust has not been established,” O’Donnell told WSN.

The central dosing session is then followed by a series of integration sessions, during which the patient makes sense of the experience and applies its lessons to their daily life.

Researchers worry that as psychedelics enter into the health care field, they may become subject to the preexisting institutional designs that perpetuate inequitable access to care.

“Inequities are a huge problem in the health care system in general,” O’Donnell said. “I think that psychedelics, just as they amplify virtually everything else, are going to amplify that problem. It’s crucial that we’re thinking on a policy level, as well as a personal and professional level.”

O’Donnell emphasized the importance of the participant-therapist relationship in any form of therapy, including and especially psychedelic-assisted therapy. She added that equitable access necessitates proper training of therapists.

“Another barrier is therapists’ training,” O’Donnell said. “We need to train a lot of people quickly if we are going to have equitable access to care. Problem is, AI cannot help us with that — at the end of the day it’s a fundamental human connection, and there is no shortcut. A psychedelic therapist is something you become.”

Kostas credits his psychedelic experience at NYU to curing his alcoholism and changing his life. Since the 2016 psilocybin-assisted study, Kostas no longer considers himself an alcoholic. Kostas’ testimony has also been featured on other outlets including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and NBC, in addition to other major news outlets.

After the trial, Kostas founded the Apollo Pact, a nonprofit that advocates for the clinical use of psychedelics while lobbying Congress to secure federal funding for psychedelic research. In their advocacy efforts, Kostas and Michael Bogenschutz, the director of the CPM, present NYU’s FDA-approved clinical trials to treat mental illness with psychedelic-assisted therapy at the Psychedelics Advancing Clinical Treatments caucus, a congressional caucus for increasing awareness and supporting federal funding for psychedelic research. With regard to the legislative advancement of psychedelic care, Kostas expressed some concerns about giving people false hope.

“In the case of state initiatives, like Oregon and Colorado, folks are citing these clinical trials and promising research, but voters may be under the misconception that they would have the same quality and standards of care as I did at NYU or someone else did at Johns Hopkins, which unfortunately isn’t the case.” Kostas said.

Therapeutic training, Kostas believes, is critical to ensure accessibility and high standards of care to meet increased demand as psychedelics enter the mainstream clinical sphere.

“Part of our effort is to let Congress know that it looks like it will be FDA-approved, so we need to get ahead of this and train therapists so that there are enough to handle the demand,” Kostas said.

Kostas credits the success of the trial he participated in to the psychotherapeutic team. “The psilocybin certainly helped me get to a point where I could work on myself and become aware of what I was dealing with and the alcoholism. But the whole team is why I had the outcome I had,” Kostas told WSN.

As a leading institution in the resurgence of research, the team at the CPM says it is devoted to education, training and advocacy in the clinical psychedelic field as it continues to emerge. Researchers say that they are looking to the future.

“Not only are we one of the first institutions and have done some of the more prominent work, but we also are really committed to being at the cutting edge of the field as it continues to emerge,” O’Donnell told WSN. “Even as people start adopting things into the mainstream, we are going to continue to try to innovate and understand how they are working and consider different models that may make it faster, more effective, more equitable. We are interested in all the different dimensions of this field.”

Taking a social justice approach on this burgeoning field, the NYU Student Association for Psychedelic Studies will host the first annual NYU Symposium on Psychedelic Justice on April 22.

Leadership at the Center for Psychedelic Medicine sees a bright future for psychedelic therapy. As they facilitate a reconsideration of our relationship with nature, consciousness and ourselves, the psychedelic revolution is arriving at a crucial time. In the context of the digital, mental and environmental crises that define our contemporary moment, psychedelics may help enable a new way of thinking that promotes necessary change.

“This is no small thing,” Pollan said. “In fact, our survival as a species may depend on it.”