How an NYU college came to possess the remains of over 200 Indigenous people, and how they were forgotten for 25 years.

Feb. 6, 2023

How an NYU college came to possess the remains of over 200 Indigenous people, and how they were forgotten for 25 years.

Feb. 6, 2023

In December of 2022, a convoy of U.S. Navy trucks left the loading docks of the building that houses NYU’s College of Dentistry. The trucks were headed to California — specifically, the native lands of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians.

They contained material foreign to most dentist offices, though: Human remains belonging to at least 63 deceased Indigenous individuals.

This story begins 66 years ago, when the remains of 264 Indigenous people came into the possession of NYU Dentistry. For a majority of that time, however, the college claims it did not know the remains existed.

“It’s really unfortunate that the NYU College of Dentistry does not know its own history,” said Melanie O’Brien, the manager of the federal program that seeks to repatriate Indigenous remains and artifacts.

The remains can be traced back to one NYU professor who received them in 1956 from the National Museum of the American Indian’s Department of Physical Anthropology and kept them in his personal laboratory for 17 years. The college did not keep records of what he planned to do with them, although it maintains that they were never used for research. After the professor, Theodore Kazimiroff, retired in 1973, the remains were kept in a storage room for another two decades, until they were “rediscovered” in the late ’90s. It took another 10 years for the college to inventory the remains and identify their tribal affiliations.

NYU is one of the hundreds of universities and academic institutions across the country that have had to grapple with the complexities of returning Indigenous remains that were long in their possession. The university’s record of returning the remains it has held actually ranks above average as compared to other institutions across the country with collections of Indigenous remains. But this took decades to achieve.

Out of 609 institutions nationwide that reported possessing Indigenous remains, NYU ranks 235th, having returned more of its collection than 376 institutions. Over 75% of the remains it held have been returned.

In comparison, Columbia University’s anthropology department has made the remains of 14 Indigenous individuals — which accounts for the entirety of the university’s former collection — available for return to their respective tribes.

As the trucks carrying the remains belonging to the Chumash people drove away this past December, the remains of another 50 people awaited repatriation in a storage room elsewhere in the Dentistry building. They represent a fraction of the approximately 110,132 remains held by academic and federal institutions across the United States.

The return of ancestral material to the Chumash tribe took place in accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, a 1990 federal law which protects the rights of Indigenous people to claim cultural artifacts and the remains of their ancestors. The law also requires that institutions identify any possible cultural and geographical affiliations of any remains they house.

Institutions are required to report inventories of their material to the federal government and must discuss those inventories with any tribes that may be affiliated before making a judgment about the origin. If tribes are aware of these inventories, they can request more information from the institution.

According to a ProPublica investigation, published in collaboration with NBC, 10 institutions hold approximately half of reported remains that have not been made available for return to tribes.

Shannon O’Loughlin, the chief executive and attorney for the Association on American Indian Affairs, who worked on the NAGPRA Review Committee in 2013, said that a majority of the unreturned remains have been labeled “culturally unidentifiable” by the institutions that hold them. O’Loughlin added that many institutions have used this classification as an excuse to retain possession of the remains they hold. (NYU has five remains which could not be geographically identified. All five were made available for repatriation.)

The documentation collected in NAGPRA databases and maintained by the National Park Service is crucial, O’Loughlin said, because it can help connect present-day tribes to their ancestors. “Every inch of land” in the lower 48 states and Alaska can be linked to Indigenous tribes, she said.

Remains awaiting return at NYU have been found to be affiliated with tribes in California, Illinois, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota and Pennsylvania.

Rachel Harrison, a spokesperson for NYU, explained that the university did not characterize the remains as “bodies.”

“The remains that NYU College of Dentistry received from the [National Museum of the American Indian] were cranial and mandible bones,” Harrison wrote to WSN. “They were not ‘bodies’ or complete skeletal remains.”

Scholars of anthropology emphasize that the language used to discuss repatriation of Indigenous remains carries immense weight.

“These were people, ancestors, individuals and relatives — not bones,” O’Loughlin said. “The language used by institutions to refer to these people can be telling about how they feel about them.”

The first set of inventories filed by NYU’s College of Dentistry, allowing the school’s possession of Indigenous remains to become public knowledge, came in April of 2009 — 13 years after the federal inventory deadline set when NAGPRA became law.

“We did not get started on the efforts to audit and repatriate the remains as early as we should have,” Harrison, the NYU spokesperson, said.

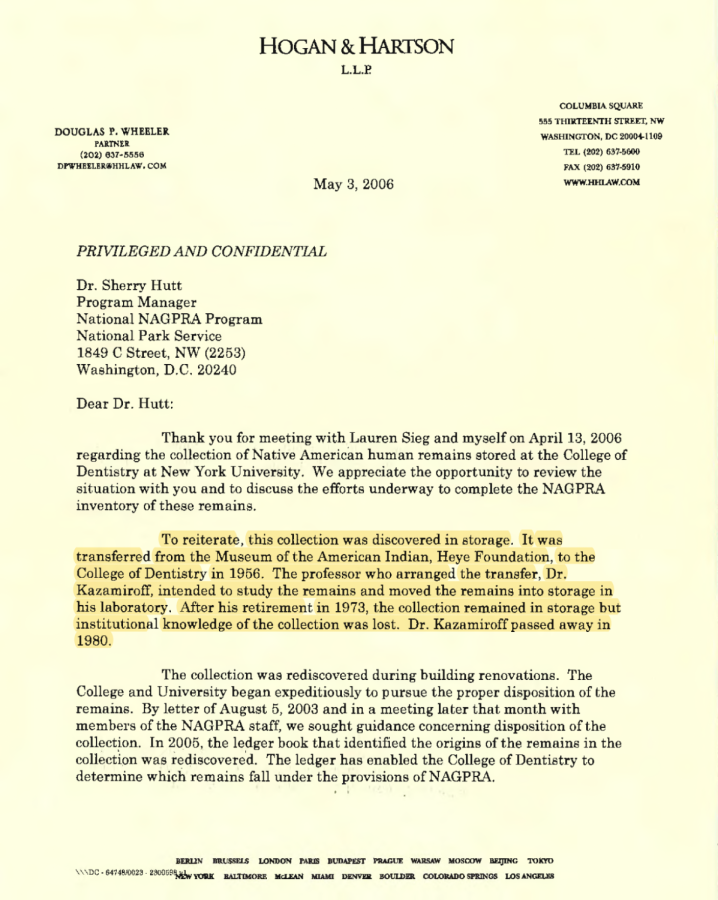

Douglas Wheeler, a lawyer for the College of Dentistry, wrote a letter to Sherry Hutt, the then-national program director of NAGPRA, in 2006. Wheeler wrote that institutional knowledge of the remains “was lost” after Kazimiroff’s retirement in 1973, until they were uncovered during building renovations. Harrison told WSN that the college did not keep documentation to date the rediscovery.

Harrison said it was “a little difficult in 2023 to reconstruct a precise timeline of what happened 25 years ago.” However, she said that administrators contacted the National Museum of the American Indian in 1997 to request that it take back the collection. According to Harrison, that request was denied.

The timeline between 1997 and 2003 is murky, but records show that the college sought legal advice from Wheeler’s law firm, Hogan and Hartson, in 2003. Harrison told WSN that the college hired the firm “to better understand and bring ourselves in line with NAGPRA.” She added that they also hired an expert consultant in 2005, who helped the college to begin the process of constructing an inventory of the remains.

In his 2006 letter, Wheeler noted that the 2005 discovery of a ledger book that identified the origins of the remains aided in the inventory’s completion.

“The ledger has enabled the College of Dentistry to determine which remains fall under the provision of NAGPRA,” Wheeler wrote in the letter. He did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

According to Joshua Johnson of NYU Dentistry’s molecular pathobiology department, the process behind the most recent return of remains began in October of 2021, which is when he reports beginning his correspondence with the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. Johnson said that officials from the tribe first visited the Washington Square campus in June 2022. The Tribal Hall of the Santa Ynez band of Chumash Indians declined a request for comment on this story.

According to archives kept by the National Museum of the American Indian and the Heye Foundation, the return of these remains in December of last year comes nearly a century after they were first taken from their ancestral homes.

Documentation from the National Park Service and the Heye Foundation shows that the remains returned to the California tribe were taken during a series of excavations along the southern coast of California. The excavations were led from 1919 through 1923 by Ralph Glidden. They were funded by Thea Heye of the Heye Foundation and the National Museum of the American Indian.

When Kazimiroff, the NYU professor who was responsible for the collection, received the remains in 1956, it was not his first foray into archaeological collection, nor his first interaction with the museum. As the first official historian of Bronx County, he had made a name for himself as one of the founders of the Bronx County Historical Society, and as a fellow at the National Museum of the American Indian and the American Museum of Natural History.

In Kazimiroff’s obituary, published in The New York Times, writer Walter Waggoner notes the professor’s experience in archaeological collection. Waggoner writes that Kazimiroff’s home at Bainbridge Avenue and 201st Street in New York City became a “storehouse of Indian artifacts.” According to a 1953 article in the Scientific American, Kazimiroff was known by his friends as “the amateur archaeologist of Broadway.” Waggoner estimated that Kazimiroff had assembled “perhaps as many as 50,000 arrowheads, clay pipes, war clubs, pieces of pottery, stone tools and harpoon points” in his personal collection.

In the same article, Kazimiroff recalls driving past a construction site for the 1938 New York World’s Fair, when he thought he saw a burned patch in the earth that looked like “the remains of an Indian fire pit.” Without permit or permission, he recalls deciding to pull over and start digging up the soil, eventually finding the remains of an Algonquin burial ground.

“Experience had taught me that in New York City it pays to dig first and ask for permission later,” he quipped.

He continued digging past nightfall, until the owner of the construction site called the police. Then he took what he found and fled.

“I piled my notes and specimens into my car and commenced shoveling the dirt back into the hole,” Kazimiroff said to the interviewer. “When I heard the approach of a siren, I lit out for home.”

Academic professionals, like Kazimiroff, have built careers off of acquiring large collections, according to O’Brien, the National NAGPRA program manager at the National Parks Service.

Today, knowledge on the subject of the remains within NYU Dentistry is still limited. In an email to WSN, Andrew Speilman, the director of the Rare Book and Historical Archives Library at NYU Dentistry, said that he had no knowledge of the remains.

In the eyes of repatriation scholars, NYU is finally making amends. But O’Brien, the program manager for NAGPRA, isn’t willing to grant them absolution for decades of misuse and neglect.

“These were the result of racist efforts,” O’Brien said.