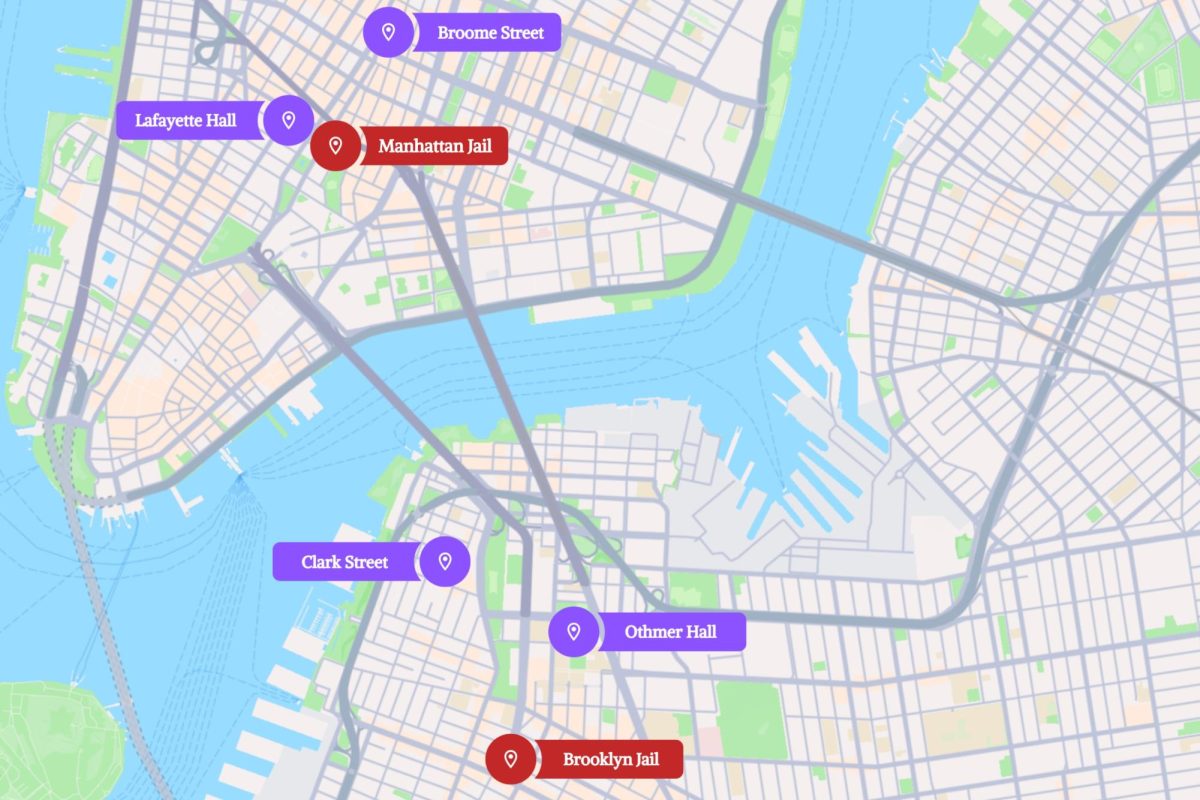

One block away from Lafayette Hall sits a barren construction site, obscured by tall wooden walls, stretching White Street in Chinatown. Aside from the looming gray of the New York County Criminal Court building, the desolate lot is markedly distinct from its surroundings — a mixture of the adjacent senior housing project Chung Pak and a series of small, no-frills Chinese and Vietnamese restaurants and local pharmacies and clinics.

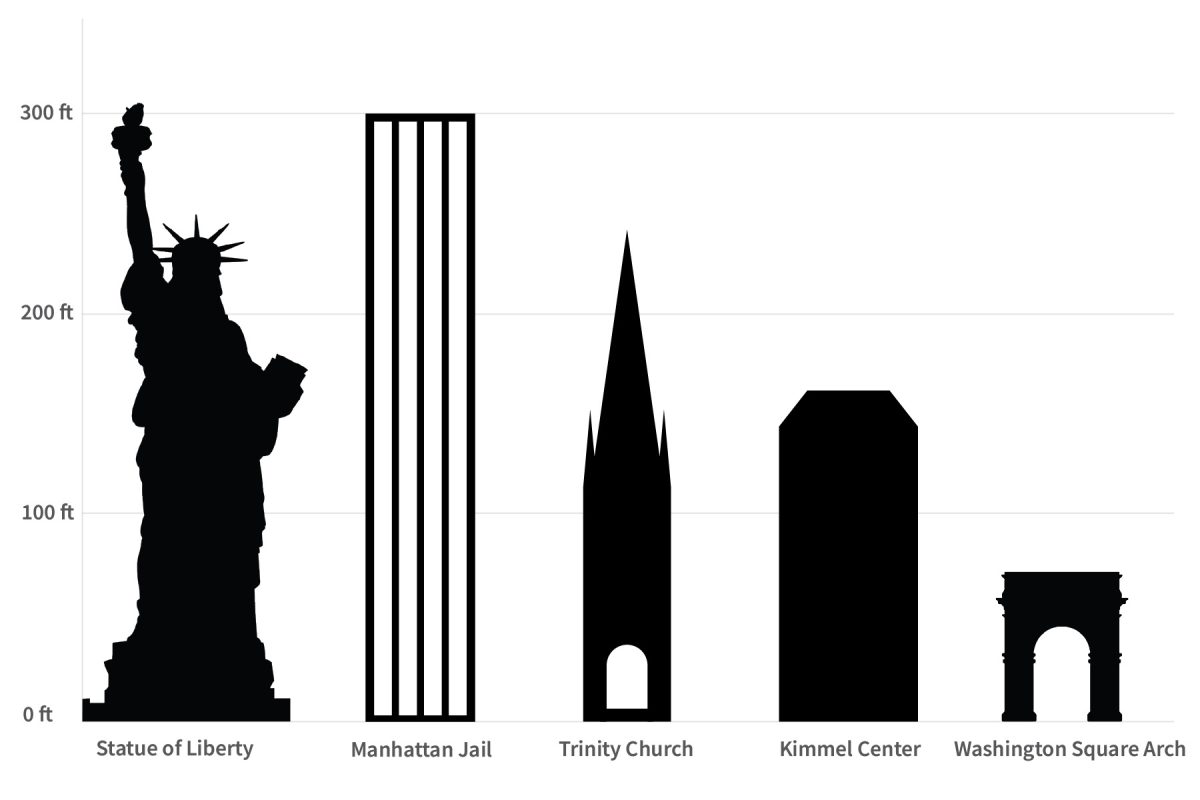

It is on this site, a two-block walk from Canal Street, where city officials are constructing the tallest jail in the world — scaling around 300 feet. And it is not the only one.

In 2019, the City Council approved an $8.7 billion borough-based plan to close Rikers Island. The plan follows years of pressure from incarcerated individuals and their families, who criticized the inhumane conditions and abuse faced by those detained across its 10 jails. To prepare for Rikers shutting down by 2026, now delayed to 2027, the city is in the process of constructing four “modern, more humane” jails in every borough except Staten Island.

Both the Manhattan and Brooklyn jails are located in direct proximity to NYU dorms. The Manhattan site stands at a less-than-a-minute walk from the upper-year dorm Lafayette Hall, and the Brooklyn site is about a six-minute walk from the Tandon School of Engineering’s main campus and Othmer Hall.

The decade-long movement to close Rikers

For some people, like longtime anti-Rikers activist Darren Mack, the new jails represent promise. Mack, who co-founded the Campaign to Close Rikers in 2016 and sits on the Commission on Community Reinvestment and the Closure of Rikers Island, was detained at Rikers for 19 months as a teenager before finishing his 20-year sentence upstate.

“When I was on Rikers Island, the population was over 20,000,” Mack told WSN. “It was a time when what was happening in there — conditions, brutality, violence — it was out of sight, out of mind. There wasn’t no advocates, pushing or addressing the conditions there. It was basically everything goes.”

It was Kalief Browder’s suicide in 2015 that drove Mack and other formerly incarcerated individuals to spearhead a movement to close the jails. Browder had been accused of stealing a backpack at 16 and spent the last three years of his life on Rikers, two of which were in solitary confinement. Now, Mack is actively advocating for the borough-based plan in New York City.

The borough-based jails are built on three main tenets — being smaller, safer and fairer. The city’s current network of jails consists of 11,300 beds, and the four replacement jails are set to hold 4,160 beds combined, in addition to ample space for educational, mental health and medical programming. But its defining feature is the fact that these jails are located on existing, smaller jail sites in the boroughs, with the exception of the Bronx, which Mack said will be more accessible to family members, attorneys and activists.

“I remember when the [Brooklyn Detention Complex] was open, and we would get calls from people ‘yo, there’s no heat,’ so we [would] protest in front of the facility, the news would come out, and then elected officials come out and they would try to address the problem,” Mack said. “You can’t do that on Rikers Island. There’s a bridge there, and you can’t access the bridge without permission from the Department of Correction.”

A carceral cycle

But for others, the harrowing shadow of a skyscraper jail symbolizes a broken promise. Since its approval in 2019, a diversity of interests have come together in resistance to the borough-based plan. Local residents and businesses fear its effects on their community, while abolitionists are skeptical that creating new jails will “fix” the existing ones.

For Jan Lee, a third-generation Chinatown resident and former business owner on Mott Street, closing down Rikers is not the issue. Lee is an organizer with Neighbors United Below Canal, a leading group in the fight against the Manhattan jail. He said that last year’s demolition of the existing Manhattan Detention Complex, colloquially known as “The Tombs,” to make room for the new jail set a bleak tone for how the city plans to work with the community.

(Grady Rajagopalan for WSN)

According to Lee, the demolition had created cracks in the wall of the adjacent senior housing project Chung Pak, which, ironically, had been built in 1992 as a compromise between the city and the thousands of Chinatown residents that protested The Tombs’ construction. The next-door Charles B. Wang Community Health Center relocated part of its clinic due to “frequent noise and leaky ceilings” during the demolition.

“It’s not like a small debt,” Lee said. “This was 80 feet of cracks, and by the grace of God, they didn’t hit a structural column, but they were only a few feet away from it.”

Nora Rai, a Steinhardt senior who’s been living in Lafayette Hall for the past two years, hadn’t been deterred from choosing to live in the dorm despite other NYU students expressing fear over its proximity to the courts and The Tombs. But sitting on a bench in Collect Pond Park, overlooked by the New York County Criminal Court, Rai explained that the idea of a skyscraper jail is a daunting reality to confront.

“I think it’s just the consistency of jails being placed in Chinatown, and the fact that it is the tallest jail in the world is kind of why it’s much more larger than ‘there’s been jails here before, like oh, [One Police Plaza] is here, like why the outcry?’” Rai said. “You shouldn’t have to just settle for something just because it’s already been there for a long time.”

Lee, whose family has lived in Chinatown for generations, said these jails have followed a cyclical pattern since 1838, continuously built then torn down in the neighborhood, which already houses the New York City Police Department’s headquarters and New York County’s courts, under the guise of reform.

“They tear a jail down, they make the next one bigger,” Lee said. “If jails were the answer to rehabilitation and making people find a way out from the carceral system, they wouldn’t be building them bigger every single time, and what we’re looking at now is the largest jail ever to be built, and it happens to be in Chinatown.”

The previous jail on the construction site closed in 2020 for similar reasons to Rikers — poor conditions and severe overcrowding that no longer made it fit for incarceration. And delays up to 2032 in the opening of the borough-based jails to accommodate an increase from 886 beds to 1,040 under the Adams administration has only heightened skepticism of the plan as an actual step towards closing Rikers by 2027.

Cindy Hwang, a housing organizer for the nonprofit Cooper Square Committee living in Brooklyn and an organizer with the mutual aid group Brooklyn Jail Support, found a similar pattern with the Brooklyn site in a recent zine she worked with other abolitionists to create.

Hwang has been active in BKJS for almost a year, coming to their table in front of Kings County Criminal Court every Friday from 2 p.m.-2 a.m. to distribute trays of hot food, juice, cigarettes and informational flyers denouncing the new Brooklyn jail to people released from the jail across the street.

“I looked at a bunch of old news articles about the former jail called the Brooklyn House of Detention, and I found out that it had actually been built as a replacement for another jail called the Raymond Street Jail that was on Ashland Place in Fort Green [Park]. It’s like history repeating itself,” Hwang told WSN. “Raymond Jail was denounced as this really horrible, abusive, medieval dungeon — people were like, ‘we have to close this awful jail and build a new one,’ which became the previous Brooklyn jail.”

But the Brooklyn jail’s effect on the everyday lives of residents is still unclear. Tandon junior Anuraghav Padmaprasad said that despite the Kings County court system’s longstanding proximity to the campus, for many Tandon students, it’s extremely easy to live in its bubble, going to class unaware of its existence.

“If I would give a number, like loosely stating this, 70% of the people have no idea about even the other buildings around Tandon,” Padmaprasad said. The number of engineering students who don’t explore the city is higher than usual [than] like main campus.”

At odds with community needs

Although the city has been hosting Community Design Workshops across the four boroughs to incorporate input from the community, Lee said that plans came mostly pre-decided and that community feedback was not a genuine aim for officials. Lee argued that actually listening to residents would be to address their calls for affordable housing, especially in the surrounding area of the jail, where centers like Chung Pak currently have a waiting list of nearly 5,000 seniors.

Because of the preexisting court buildings, Chinatown is largely hemmed in from expanding southeast, meaning every site within the neighborhood could be valuable space for affordable housing in one of the city’s lowest-income areas. Nonprofit organization Welcome to Chinatown created an alternative plan where the current site would be transformed into affordable housing and a public green space for residents, and the jail would be relocated to Metropolitan Correctional Center — a currently unoccupied federal prison on Park Row.

“It’s still in the vicinity of the courts. It’s a totally secure space and it used to be a jail, so there’s no reason it can’t be a jail again,” Lee said. “Maybe it needs to be a little bigger, maybe it needs to be modernized, but it’s ready to be renovated while we build housing for Chinatown.”

However, Mack argues that these plans to relocate only expose how NIMBYism, rather than genuine calls for decarceration, has always been at the root of resistance against the borough-based plan.

“We was like, ‘we could work together to decarcerate and get the population even further down,’ but some communities prefer to just deal with that issue,” Mack said. “And like, even now that’s that same community that was saying ‘not in my backyard,’ now they’re saying, ‘build a jail over here, not in my community, you know?’ If that’s not NIMBY, then what is it? … We’re accountable to those survivors of Rikers, those who’ve lost their loved ones on Rikers Island. This gotta be done if we want to get our city to move past mass incarceration and get Rikers closed.”

Combatting incarceration at its root — racism, poverty, homelessness and a lack of mental health and substance abuse resources — cannot be fixed by the jails alone, said Terrence Coffie, a professor at the Silver School of Social Work and a staunch criminal justice advocate after experiencing incarceration himself. The jails do not guarantee a transformation of the violent culture at Rikers, Coffie said — we do.

While the city recently secured over $50 million for expanding mental health programs, with supportive housing and mobile mental health treatment teams, both city and federal governments have also made steps in the opposite direction. In New York State’s latest budget, Gov. Kathy Hochul expanded police and clinicians’ ability to forcibly hospitalize people who they believe are experiencing a mental health crisis amid ongoing fears for public safety, with President Donald Trump following Hochul up with a similar executive order.

“ I care more about the internal restructuring than I do the external restructuring,” Coffie said. “Wherever you put it at, that’s where it’s at — however that happens. If I take dirty water and I pour it into four smaller cups, it’s still the same dirty water, just for smaller cups.”

Contact Julia Kim at [email protected].