If you’ve ever paid attention to the architecture of Bobst, everything is angular. There are no curves in that god-forsaken building. God-forsaken not in the sense that it’s dilapidated — rather, that it’s uninspiring. The atrium floor is mesmerizing, but as you look up, physically mimicking the act of worship, all you see are square light panels: bleak, bland and blinding. Perhaps it’s a blank canvas, one on which you can project your own dreams about making it in New York City.

New York cannot be the city of your dreams

Millions flock to New York every year to witness one of the greatest cities in the world — and perhaps be a part of it. Idealism for New York might have gotten you here, but you need to abandon it to move on.

April 23, 2022

New York, New York

New York’s greatness is one of modernity’s most fascinating myths capturing the most archetypal imaginations, so ubiquitous that it smudges the epistemological line between fiction and reality, where mythology becomes history and history becomes mythology.

Mythology signifies the will to exist and the denial of death. Predecessors mythologized with vigor to inspire and reinforce the meaning of existence. But as vigor withers away, myths stultify into rigid norms and traditions, cliched at best and disillusioned at worst.

The Statue of Liberty stands as a towering monument to American myths like freedom, opportunity and hope. It was the symbolic beacon for immigrants of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Now it is a tourist destination, a small landmark to look out for if you’re enjoying the south-facing views from Lower Manhattan, dwarfed by the downtown skyscrapers. The Statue of Liberty represents an idealism that has faded into history: still there, but not what it used to be.

The Western God was handed his philosophical death sentence at the turn of the 20th century. In the search for a secular belief to fill the ideological void, New York City mythologizes the greatest atheist narrative of the modern time. At the time, New York was the commercial nexus of the United States, in charge of almost half of all imports and exports. Underpinned by its diverse population and American capitalism, the culture industries — the standardization and mechanical reproduction of cultural and artistic works under capitalism — in New York rose to prominence. With the aid of Madison Avenue advertisers, the culture industry fulfilled New York’s postmodern prophecy when it manufactured a simulacrum of New York City so towering it overshadows the original. New York is what it is, but its self-perpetuating myth edges toward pure simulacrum.

437 Madison Avenue houses the headquarters of the Omnicom Group, one of the world’s largest advertising firms. The Omnicom Group is the successor of Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn and Doyle Dane Bernbach, two of the most historically important advertising firms in New York City in the mid-20th century. Back then, advertisers congregated around Madison Avenue, turning the avenue into a metonymy for the advertising industry. With the advent of television in the 1950s, advertising became a key cog in the culture industry. Housed in New York City, the advertisers propagandized New York as one of the greatest cities in the contemporary cultural zeitgeist.

The Good Old Days

New York City lies in the unconscious of the Gen Z zeitgeist since the turn of the millennium, at least in part due to 9/11. Growing up in Taiwan, I have always known of a city far, far away called New York and learned of its conventional magnificence. In a way, I consumed reproductions from the culture industry, the standardized narrative of New York as one of the most developed cities in the world. I would naturally want to visit this city, be awed by its vibrance, and shocked by its abhorrent expensiveness and mechanical pace.

It was not until I started watching Casey Neistat vlogs and getting into photography that the myth began to take a toll on me. Back in 2015, Neistat made daily vlogs documenting how he hustled his way from a broke nobody to an indie filmmaker in New York City, glorifying the city and developing a cult-like following around his relentless — and perhaps toxic — work ethic in the process. His vlogs and histories of how photographers made their name in the city seeped into my consciousness, nourishing a quasi-religious impulse that blossoms into an idealism about New York City.

The second floor of 368 Broadway was Casey Neistat’s personal studio, where he filmed the majority of his vlogs. Known for mottos like “Do What You Can’t,” Neistat came from Connecticut with nothing and made a name for himself in New York as an independent filmmaker. In 2015, he brought the daily vlog genre into the public consciousness. Through hundreds of daily vlogs about his life as a New York City filmmaker, he borrowed from the old idea of New York as the city of endless possibilities and created a 2010s myth — a great cinematic story about the virtues of relentless dedication and a contrarian approach to life. Neistat no longer lives in New York City and 368 is now a studio of its own without him.

That was my sole reason to come to NYU — “to be a part of it, New York, New York.” Coming to the city as a college student, I thought I had devised an ingenious solution to take risks for four years in this city without having to worry about survival while doing so.

Unbeknownst to me, idealism is like the Titanic, charting its course toward New York City with grand ambitions, oblivious of its impending doom. I wanted to make it as a street photographer in New York City, like how street photographers before me did in the good old days. It wasn’t until I walked into the museums in the city that I realized everything I wanted to do and could think of had already been done. There are pictures of every single street corner of Manhattan. Specializing in street photography no longer has the same vigor and prestige as when Joel Meyerowitz walked up and down Fifth Avenue for decades or when Bruce Gilden snapped flash photos of people right in their face on the streets of New York. Even if I were to make it, lined up in front of me are hundreds of more experienced and talented street photographers. The frontier has settled into an established town, treasures discovered, legends made and the unknown explored.

A statue of Diane Arbus in the southeast corner of Central Park is one of two statues in the park honoring women’s historic achievements. Compared to the larger-than-life monuments of historical figures in Central Park, the life-size figure of Arbus encapsulates the essence of her work and character as a photographer with perhaps the keenest perspective to roam the streets of New York. Arbus’ mid-century work gave exposure to the marginalized and the underprivileged; in her time, this was pushing back against the current, breaking stereotypes and creating new avenues for representation. Her presence as a humanist photographer lives on as her statue continues to bring joy to the people of New York.

Cultures are most energetic, disruptive and exciting at their genesis. Once they begin to propagate as a form of idealism, they have already stultified into norms, traditions and institutions. Photography seen in the galleries in the most run-down part of town is vitalizing. Photography seen in the Museum of Modern Art means it has established itself in the public consciousness. Photography in the Metropolitan Museum of Art means its creativity has legitimized into a tradition. Photography seen on the walls of luxury condos and skyscrapers means the culture industry has successfully appropriated the art, and the cause is lost. Idealism gradually becomes untenable. Holding onto nostalgia is walking forward in thickened mud or trailblazing in known territory.

The Eternal Return

The culture industry manufactures idealism into the oppressive structure it once set out to disrupt. History reiterates itself. The stultified structure awaits the next revolution to topple its oppressive regime. The process of genesis, growth, institutionalization, destruction and recuperation endlessly reincarnates itself.

To move beyond idealism means to trace the movement back to its roots and recuperate the creative energy, to interiorize the exteriority of New York City propped up by the culture industry and to reverse the postmodern mimesis. In lay terms: regulating social media use rather than consuming products of mass media, straying away from daily routines, and paying meticulous attention to your reaction to every irregularity in the city might help to move beyond the cliche idealism. Even though post-structuralists have deconstructed virtues like sensibility and intuition, the Kantian pure reason, searching for individual interiority serves the same function as identifying discursive systems and ideating counternarratives the post-structuralists embrace.

Inward reflection fuels the light that guides us out of the looming specter of stultified idealism. Instead of conforming to what New York City is, make New York City your own. New York City cannot be the city of your dreams, but it can be the city on which you build your dreams.

Out of the east-facing window at 80 Lafayette Street is the bland exterior of the New York Civil Court. A glimpse of the city hall and the Thurgood Marshall Courthouse is visible off to the side. My seventh-floor neighbors abhor the plain view as they dream of the skyline view enjoyed by the upper floor residents. I like the plain view. I look at it every time I sit at my desk to do work. It doesn’t constantly remind me that New York City is a towering city. It lets my imagination run free.

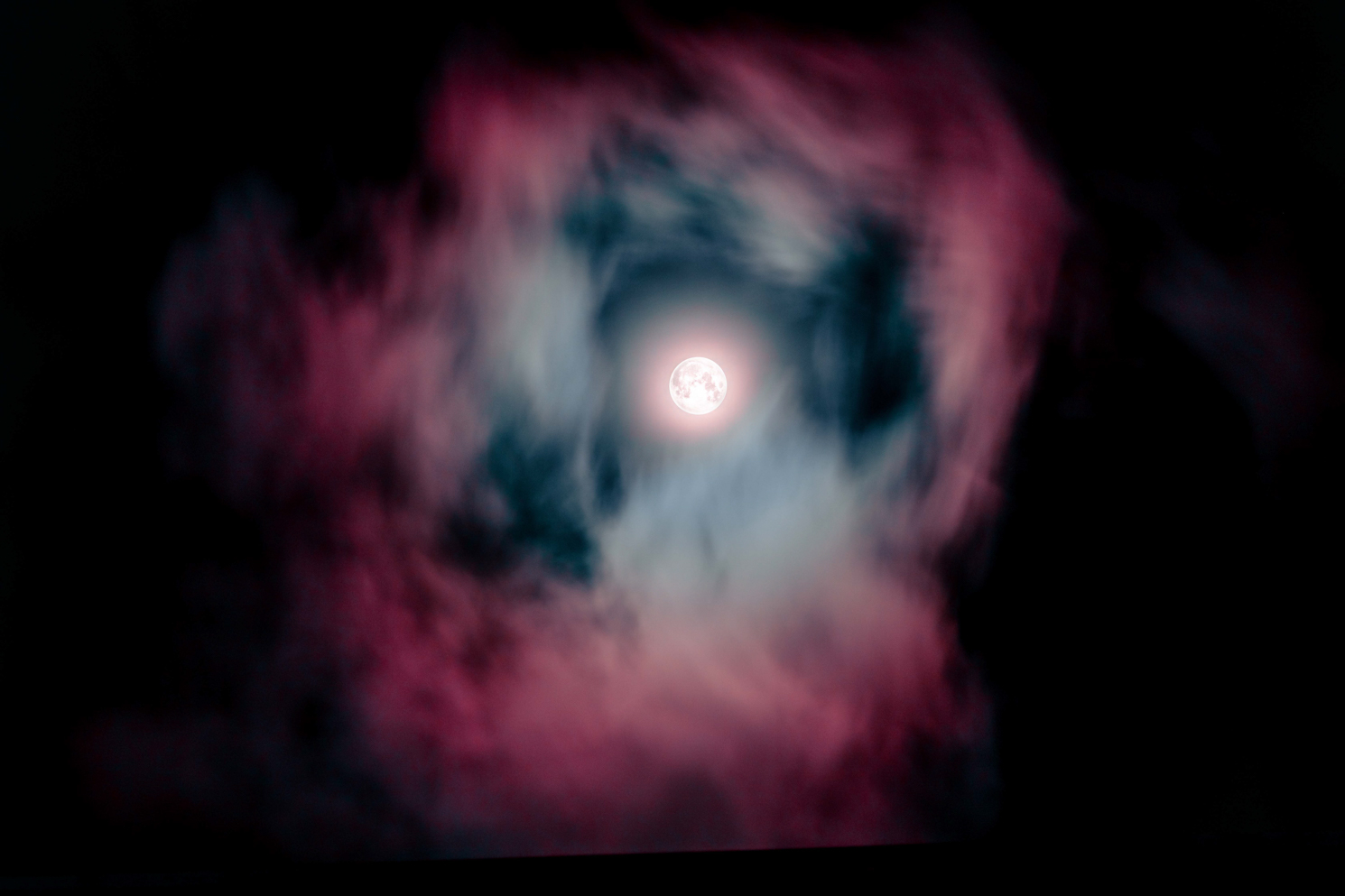

Street photography is about finding the surreal within the real. The surreal breaks free from the constraints of the real, norms and traditions, opening up new avenues. In this case, the avenue is Seventh Avenue. At the intersection with Greenwich Avenue, the steam coming from the manhole, shining under the street light, resembles how the moon would shine onto shifting clouds.

Taken on the first snow day of 2022, this scene casts the city in a light contrary to its conventional image. New York can be quiet, solitary and calm despite the heavy snow. There are no people, but you can put the pieces together. The scene shows no iconic New York City streets, but it’s iconic New York City.

I don’t know what is going on here. The person on the right was taking a picture of the unconscious person on the left just before I took the photo. That’s all I know. No one seemed to care.

Staying in the city for too long messes with the way I look at things. New York City, with its linear streets and orthogonal intersections, constrains space into inorganic lines and sharp angles. Every element is in rectilinear motion. This is especially the case for Manhattan, where the grid system dominates the landscape north of Houston Street. Generations of photographers have found their way through the tightly constrained space, finding every way possible to extract interesting compositions out of the limited perspectives either by shooting with a long lens from afar or by getting up close and personal. Another way to navigate around the spatial constraints is to go into the parks, where boundaries are less demarcated. It is in the parks where I find the most liberating compositions.

Unconstrained by the linearity of the regular city streets, the parks liberate the imaginations and compositions. This scene is a self-portrait of the photographer, seen contemplating how New York City is wrapped up into a giant ball of cliches and how to move beyond.

Update: Casey Neistat moved back to New York City in the autumn of 2022.