So what are we?

November 30, 2015

“So what are we?” It’s the question that defines our generation’s attitude toward love and relationships. We ask it of ourselves, our significant others, our hookup buddies: What are we doing? What is this thing that is happening? How do we label it?

Each of these pieces, both in the issue and on our Under the Arch blog, tries to tackle this question from a different personal perspective.

Though some might argue that love is an eternal concept, each generation grapples with it in a different way. The importance of the personal narrative, to both the writer and the reader, is that it allows us to discuss romantic love in all of its different stages and forms, whether it’s hookup culture or long-term relationships.

I want this issue to provide a space where, as a community, we can begin to showcase and share our experiences as a way to understand the way relationships work — or don’t — instead of trying to dissect every situation and define every detail.

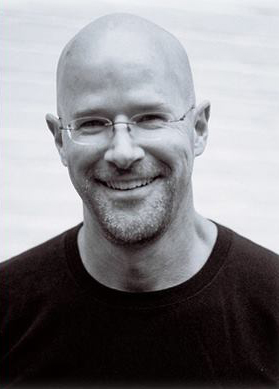

Interview with Modern Love editor Dan Jones

Dan Jones is the editor of Modern Love, a weekly New York Times column that features personal narratives from people grappling with the concept of love. WSN chatted with Jones about the evolution of modern love, how we understand it and what it means to college students.

WSN: What do you think the role of the Modern Love column is?

Dan Jones: I think we learn through storytelling, and because these are all real stories that are very emotional, there’s always a problem and a conflict in them. I think that people identify with that, and they appreciate hearing how someone has come through something and what they’ve learned from it.

WSN: Do you think that there’s a way to define modern love, and if there is, has that changed over time?

DJ: I think one change that’s happened is that we have more ways that we can try to not show our vulnerabilities. Technology is just a tool, it’s not bad or good by itself. If you’re the kind of person who doesn’t want to show your cards or doesn’t want to show your feelings, I think it can sort of help people avoid confronting their feelings. But there are two sides to it. People have these very deep, electronic-only relationships where they feel like they can confess anything online as long as they’re behind that screen.

WSN: Do you think that college students have a more naive viewpoint about love?

DJ: I would never generalize to that degree. We’ve had three college contests now over seven years, and what I find interesting and kind of refreshing is that college students seem to have these highly romantic notions about how their lives should play out, but they’re also really deeply cynical. They think it’s never going to happen that way. So those two things are kind of hard to reconcile. How you can have really romantic ideals but also never believe that’s going to happen on some level? And I’m not sure why that’s spread so wide, but in so many of these essays, people talk so much of the coarseness of the hookup culture, and all of that. In some of these essays, people are desperate for real emotional connections. So I don’t think that’s naivete really, I think there’s some sort of split between what we want and what we feel like we can get.

WSN: How has the column impacted your life?

DJ: I’ve been married for decades. I think the first impulse for so many people is to be judgemental. I see that in response to columns, stories, where people are confessing being confused, or not being able to figure out their love lives. It’s complicated. To try to simplify it into a set of rules or some sort of judgement is naive. I really appreciate the complexities of relationships and what people go through, and I feel very empathetic toward people going through

those difficulties.

WSN: I think that it’s really difficult to define what modern love is, especially at a college age. Would you agree that the function of the column is to broaden people’s perspectives about love?

DJ: A lot of readers like to read about their own lives and their own situations, but I really like to read more about people’s lives who are not like mine, and I’m really curious about these strange situations that people find themselves in, and the hard choices they face. So I feel like the extent of the column represents broad experience due to that curiosity of mind, of really wanting to hear it all.

The kiss list

My first kiss was a mess. It had all the hallmarks of a first kiss — the near miss, the awkward angle, the realization of how strange it is to put your mouth on another person’s mouth and then it was over. My second first kiss happened a couple of days into my freshman year of college. The third was in the stairwell of my freshman dorm. The fourth is blurry. Five and six happened the same night, and that’s when I decided to make a list.

It was Halloween. I threw on some fake eyelashes and a witch hat and went out into the world with 20 of my closest friends. We found a Halloween party in Midtown and decided for some strange reason that this was how we wanted to spend our night. We split like a search party in the crowd — the ritual our generation has become known for. Get drunk, flirt, hook up, never speak again. Number five was dressed as Caesar. He looked like an off-brand Justin Timberlake and said he was a “DJ.” He kissed me and friend-requested himself on my phone. Eventually I got bored and walked away.

Number six happened on my walk to the pizza place that same night when a young-looking Brit stopped me and said, “Excuse me, my name’s Nick, will you be my girlfriend?” I was completely caught off guard. “No…?” I said and assumed that was the end of our conversation. But it wasn’t. “Well I’ll go away if you give me a kiss,” and in a move that still surprises me today, I kissed him.

The next day, as I woke up with the world spinning and a pounding headache, I pieced together my night. To me, one drunken make out in a night was fine, but two seemed a little excessive. I don’t know what exactly I thought was going to happen because of it, but I felt like I had broken some cardinal rule: Thou shalt not make out with two people in one night. I needed to confess my sins so I reached for my phone and opened a new note: “Halloween: Caesar, British Nick.” Writing it down gave me back the control I’d lost in my drunken haze. I decided to own the moment and embrace it.

And then I went all the way back to the beginning and wrote down every other first kiss. It seemed wrong to give two random people so much importance on a note by themselves. Since that night, it has become a running list.

For a while I tried to turn my list into something more meaningful. I divided the names into categories: important, not that important, irrelevant. Later, I tried to give details — who they were, how I met them, what happened later. But it was too much. It didn’t quite matter who they were or what they mean to me now, they just all had something in common. A fleeting moment of connection, and a kiss.

Some of them were definitely mistakes, only two I wish I could take back, but a few are people who have changed the way I see love. The latter group is why I haven’t deleted my list. Seeing their names is like the tether that connects me to them. They hit me with a shock to my nervous system reminding me of how raw and open I was with them and how I haven’t been quite the same since.

As a self-proclaimed commitment-phobe, I constantly find myself trying to fight against the vulnerability of attachment. It scares me. But in some small way, acknowledging the moments I shared with these people helps me face my fears. It gives me back the power to feel when the pull of denial is so strong.

Love can go the distance

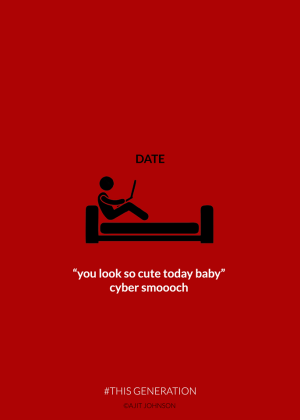

Artist Ajit Johnson gained plenty of attention last April for his art campaign called “#ThisGeneration.” Ironically, his critiques of technology-obsessed millennials went viral on social media platforms like Tumblr. Perhaps the hashtag helped. Criticisms of millennials — my generation — usually don’t bother me, but one image among the score of minimalist posters struck me.

Artist Ajit Johnson gained plenty of attention last April for his art campaign called “#ThisGeneration.” Ironically, his critiques of technology-obsessed millennials went viral on social media platforms like Tumblr. Perhaps the hashtag helped. Criticisms of millennials — my generation — usually don’t bother me, but one image among the score of minimalist posters struck me.

A figure sits on his bed, staring into his laptop’s screen. Johnson labels this exchange as a date, but it’s obvious that he doesn’t regard it as such.

“You look so cute today baby,” the figure reads. “Cyber smoooch.”

I’ve found myself in the same position countless times over the last two years. Evan and I have been together since high school, and while the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy is only an hour away on the LIRR, the school’s regimented style and mandatory internships in the maritime industry have tested us, just like any other long-distance relationship.

Since first-year students at his school have limited access to their cell phones, our primary form of communication is Skype. When he’s on his mandatory internships on a maritime vessel, I only hear from him when his ship docks in U.S. ports or when he uses an ancient relic of a computer in the ship’s engine control room.

For almost two years, our relationship has existed primarily online. but that doesn’t make it any less significant. Technology allowed us to support one another in ways that are otherwise impossible when your loved one is hopelessly far away. In high school, Evan and I would spend almost every waking minute together. We would go to swim practice together, meet during passing periods, spend lunch together with our friends and get tacos after school. Then, in the course of a week, we went from seeing each other face-to-face for hours each day to nothing. On Tuesday, we graduated; on Saturday, he boarded a plane to New York for basic training.

It was hardest in the beginning. During those first few weeks, all he had was a five-minute phone call each Sunday — and that was for his parents. Evan wrote as often as he could, but I was abroad for a month and didn’t get them until I got home. At one point, I just broke down. I remember sobbing while sitting on an airport terminal floor, calling his cell phone just to hear his voicemail message. Fortunately, he borrowed a friend’s phone and called me. I was so happy to finally hear from him, yet so broken from not being able to hear or see my best friend. He asked me why I was crying, and I couldn’t find a way to give him an honest answer.

After we started using Skype, it got better. We still experienced hardships, from petty ones where the NYU wifi would crap out, to the more serious ones where we’d rather slam our laptops shut than talk things out. Yet, it was better than not having the option to speak at all. Usually, we’re on Skype for hours on end — sometimes we just do our homework in silence, occasionally interjecting to share a funny video or bitch about our assignments. It’s a new normal.

My perceived preoccupation with my phone or laptop doesn’t make me a mindless millennial in a new age of modern love. It makes me human, with human desires to connect with the person I love, even if he might be on a ship in Pakistan or at school in Kings Point, Long Island. Technology isn’t the enemy of intimacy, it’s just a new way of facilitating it. Maybe my dates on Skype aren’t the same as getting tacos after school. But despite the distance, the love that keeps us going is still the same.

What comes after falling

Growing up I was shy and very uptight. In many ways I think I still am and I can’t name a specific reason for that. I grew up in a family of divorced parents, but even though I saw my family fall apart I still somehow held onto a very perfect model of what falling in love should be like and how relationships should be.

Then I got my first slap in the face. For the first time, little me had to deal with her supposedly perfect world falling to her feet. All it took was a regular Thursday afternoon, me, and a car with him in it. I was not greeted with a hug or kiss like the other days, and then I immediately knew.

“Sorry. I can’t do this anymore,” he said with a cold look on his face.

I still remember feeling numb and being in shock. I uttered maybe two or three angry words. I couldn’t even look him in the eyes. I opened the door, walked out and never looked back.

I went through all the stages of grief: I was mad, then sad, later angry blaming the other person for having the audacity to think he could break my heart. “Who does he think he is?” I remember thinking to myself. I never even let myself cry, as if crying would be a sign of weakness. I kept it all inside trying to be strong, to show others but mostly myself that nothing and no one could ever bring me down no matter how hard they tried.

But was I really as cold and untouched as I seemed to be? I don’t think so. In my head, I still wanted him to come back, just like they do in the movies, and take it all back. I was waiting to see him standing outside my house begging me to get back together. It was more of a matter of pride for me than an emotional need. But he never showed up and so my wish never came true. Will he ever know I wanted that? Probably not. Why? Because I did not want to seem weak.

He might never know that he hurt me, but in the end I’m glad he did. I had to be hurt to realize I needed to heal myself. It forced me to see that change was necessary. I did not want to be the little girl anymore who was afraid to feel any strong emotions and who could not speak up for what she wanted. I wanted to be more than that. And eventually I thought to myself: You simply cannot get up if you don’t fall in the first place.

It took a long time for me to come to that conclusion. It took many more wrong people, more mistakes along the way to see that I could not and did not want to keep going on that way. Now, almost three years later, I think I am slowly coming to terms with who I really am, trying not to judge myself so hard, letting down my guard, letting other people in and staying away from those who hold me back. I want to see myself grow, like a young person of my age should. One step at a time. Slowly, but surely. At my own pace.

How do you tell a boy you like him?

One time in elementary school, at the ripe age of 7 or 8, my girlfriend said she liked someone else. I didn’t really care about her, though, because I had a crush on the boy she wanted to leave me for. I never told him I liked him because, in my 7 or 8 years, I hadn’t learned how to tell a boy I liked him. The only control I had in my life was whether I actually napped or not during nap time. Any other situation, such as forbidden gay love, fell right through my fingers.

The first time I worked up the courage to tell a boy my feelings for him was old school: Yahoo! Mail. We were in 8th grade. He was one of my closest friends and straight. One night we went to see the new “Twilight” movie, but it was just as friends. All I could think about while writing the email professing what felt like love was his red cheeks when he came to get me for the movie. Email, as it turned out, wasn’t a successful conduit for the feelings of a hormonal gay 13-year-old who liked a straight boy. Writing the email gave a false sense of confidence — I could write everything I wanted to say and look it over a million times. Hitting send, however, was like getting hit with a brick. After I sent those few words into cyberspace, I couldn’t stop them.

The email was sent, but to no avail because straight boys, especially those in 8th grade, generally do not go for their gay best friend. So I recoiled back into my head and refrained from ever sharing the dreaded emotions that compelled me to write that first email again. Maybe the best way to explain my feelings wasn’t from behind a computer screen. It was okay, I told myself — I’m learning.

The next time I told a boy I liked him was in high school. He was a curly, long-haired hockey player who smoked too much weed. My life in this moment seemed to be taken straight out of the screenplay for a “Degrassi” episode. We had dates during lunch period and saw “Wreck-It Ralph” together. We texted each other about our reciprocated feelings. But a week later, we stopped seeing each other.

The digital revolution had failed me. If not through email or text messaging, maybe feelings were better expressed in person, I thought.

I wanted to tell a guy I lived with freshman year of college that I liked him a lot, like a lot a lot. After I drunkenly initiated a lackluster kiss, someone opened the door to the suite and we immediately jumped back from each other. There was no magical spark or fire that started. We just live our lives now as if it never happened. Four Loko is no one’s friend.

Since then, there have been some successes and failures, but mostly failures. Most recently, I shared my feelings in a more intimate setting: on my bed after a “Parks and Recreation” mini-marathon. It was the first of two occasions that ended with me wanting to be in a relationship and him wanting to be noncommittal friends with benefits.

Now I can’t help but feel defeated. I first thought having control over a keyboard or a home-field advantage would give me control of the real-life situation. Then I realized the constant search for control, a product of my ambitious personality, could be the main culprit — the biggest cockblock — in my unfulfilling love life.

And so I offer this advice. If your romantic life consists of relationships defined by awkward drunk kisses or flat-out rejections, try to stand back from the situation and let yourself be vulnerable — give up control. I’m not sure if it’s going to work but, next time I tell a boy I like him, I’m going to give it a try.

When we don’t talk about love

At the end of the third date, there was a sense of expectation. I stood there, awkwardly using my umbrella as a kind of cane and not quite sure what to say in this situation. In a brilliant showing by my sympathetic nervous system, I decided to say, “I’m bad with physical contact,” and run away. I learned a lot about myself that day.

Up to that point, my aversion to human contact was what I would call a lovable quirk. People could just roll their eyes when I avoided hugging and, being Irish, it wasn’t like there were a lot of kiss-on-the-cheek hellos in the family. For the majority of my life, I assumed that if I were in a romantic context I would get over it and it would be fine. But that wasn’t what happened, and that made things far more complex.

To clarify, it is not as though I am against physical contact in theory — in fact it’s the opposite. I compare it to skydiving: it’s very easy to say, “Yeah, I would totally do that,” but things change when you’re actually at the door of the airplane.

Trying to figure out what is blocking me from contact has required a decent amount of self-psychoanalysis. This is a strange concept: needing to sit down and stir through theories about why you are able or unable to do something. And in darker moments, it has led to the idea that perhaps I’m fundamentally broken and will never be able to truly connect with another person. However, the root cause of this loneliness falls somewhere else.

One thing I’ve determined is that I have a set of relationship schemas. These are a set of rules that define how a relationship should work. You meet, you get coffee, you go on a date and on and on until death. One of these steps is, of course, first kiss. Attempting this is where I discovered that maybe my schemas are wrong.

If I had to blame anything for forming these arbitrary rules, it would be sitcoms — which I watched a lot of. These created the illusion for me that there is a correct way for a relationship to work. Unfortunately, people don’t always fit perfectly into a “Seinfeld” plot. They do not operate through schema, and each relationship is different because not everyone can be classified as a Jerry, Kramer, George or Elaine.

This is not to say that I was consciously mapping out relationships. But when the same narrative gets told enough times, it becomes embedded into the mind. The world is inundated with voices that tell us what love is like, and it is only possible to hear the loudest voices in this conversation. The loudest are not always the best.

The only way to fight this is to recognize the random rules we have accumulated and develop a more complex idea of what love can be. People need to talk to one another and look within themselves to find out what they want, not what they’re supposed to want. We cannot learn about love using someone else’s definition.

Figuring out relationships without schema is hard. It’s much easier to just follow a script than to have to tell the person you’re with that you’re not comfortable kissing them yet. But the discussion is worth it.

This would be a good place to talk about how I have found someone who has helped me through my idiosyncrasies. Unfortunately, I can’t because that hasn’t happened, and I generally don’t talk about this aloud. All the more reason to start.

Lastly, a case for why we need to talk about love in the first place. It can seem like it is a frivolous topic, but love impacts all of us deeply. If we want to connect with others, we cannot try to fit them into the vision of how we see the world. And at the very least, talking to others about love is a great starting point to loving others.

Breaking marital tradition to find ourselves

As we grow up, we are constantly reminded of gender roles especially when it comes to relationships — everything from men having to “make the first move” or being the ones to propose to women having to take their husband’s name.

Foremost, society has imposed a formulaic narrative for women that goes something like this: go to school, graduate college, get a job, find the right guy, settle down, get married, give up your career, have kids. It’s not that there is anything wrong with this way of life. It’s only wrong if women do not choose this life for themselves but rather choose it because they feel as if it’s their only option. With the new wave of feminism, women have been fighting this traditional way of life for over a decade.

While my parents’ marriage looked pretty traditional on the outside, there was a distinctive quality about their relationship which was not. For one, my mom worked. Many wives in my hometown became stay-at-home moms post-marriage. My mom never stopped working. My dad’s job allowed for more flexibility so he was the one driving me to dance class, helping me with my homework and making dinner for my family. I love my family, I saw how seamless my parents’ relationship was and their dynamic became my ideal. From a young age, I was already challenging society’s traditional relationships without a second thought.

Tradition, as per the Oxford Dictionary, is defined as “the transmission of customs or beliefs from generation to generation, or the fact of being passed on in this way.” From family traditions to societal traditions, the fact of the matter is, time changes things. We grow up, we evolve, we make new traditions. And millennials seem to be making more new traditions, or a lack thereof, than any previous generation.

Twenty five percent of millennials will never get married. If they do, the average age for marriage is 27 for women and 29 for men. Many of us would rather, and often do, live with our significant other instead of committing to marriage. Some may argue that this is because of our generation’s commitment issues or fear of labels, but perhaps it’s because of the conventions marriage imposes on us. With marriage comes added career and economic pressure for men while women see themselves giving up their previous lives for a new one filled with childbearing and domestic duties.

Personally, these bleak outcomes are what frightened me most about marriage. My ideal future does not coincide with what society says it should look like. Society’s idea of a future for me unsettles my nerves. What if I don’t want to take my husband’s name, what if I don’t want kids, what if I refuse to sacrifice my career? At the root of all of these questions is will I find a guy who has the right answer to all of my questions?

To be honest, marriage is the farthest thing from my mind. The dating culture at NYU, in my opinion, is nonexistent. Everything from internships to part-time jobs and my grocery list cross my mind on a daily basis. Long term, the things that cross my mind range from where I will be getting my first apartment — SoHo or Brooklyn? — and what job I will have in 5 years. Not who I will be settling down with. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. We should be more concerned with our careers, goals and other aspirations. Now is the time to be selfish.

Email Gabriella Bower at [email protected].