The Body Issue

November 16, 2015

Personal Essay: Flesh

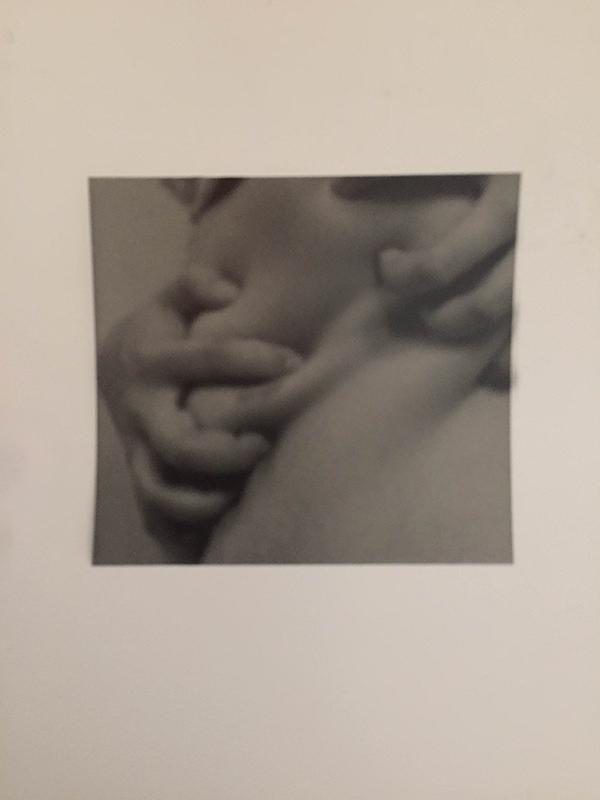

Five, 10 and 21 — the number of surgeries I’ve had, scars left on my body and inches of intestine removed. Last summer during my Intro to Photography class, I took photos of the pink scars lining my torso. I was not thinking about body image. In fact, I barely think about it. When you have a chronic illness like Crohn’s Disease, your weight and health fluctuate so much and so rapidly that you rarely have time to worry about your appearance. Yet when I presented my photos to the class, the professor didn’t seem to notice the scars.

The photos were zoomed-in shots of my body. I had set the self-timer on the camera so that I could use both my hands to grab my flesh to look like I was trying to rip my body open, just like all of the surgeons that have sliced my flesh since I was three years old. In the developing lab, I spent over an hour re-adjusting the contrast so that my scars were distinct from the rest of my skin. My goal was to show a side of me that is otherwise invisible. I am not skinny or fit, and while I’m a bit pale, I don’t really look sick. This was my chance to reveal something I had kept hidden for so long, and here I was — about to share it with a group of people I had only known for a few weeks.

After pinning up my photos next to my classmates’ work, I nervously awaited my professor’s critique. Did I use too much contrast? Was there not enough versatility? I went down the checklist of everything that I could have done wrong, when the teacher finally arrived at my piece. I perked up and leaned forward to hear what he had to say. “Ah, I see. Yes, I get it,” he remarked, “We’ve all got a little pudge on us.”

I immediately sank back in my chair. There was nothing that could have prepared me for that response. All I could do was nod my head and twiddle my thumbs. In my life, a lot had been done to evaluate my body — CT scans, MRIs, colonoscopies, ultrasounds and biopsies. Yet, here my body was being evaluated by a non-medical professional, in a way that would never possibly help me lead a healthier, better life. My scars are not large, but they are certainly not imperceptible.

The professor’s comments left me feeling confused and insulted. I couldn’t quite grasp why the soft flesh on my body mattered–having fat on my body meant that I was relatively healthy, but it became now it seemed that my fat was worse than my scars. On my walk home from class, I was reminded of a doctor who once examined my freshly post-surgical torso. She and a team of medical interns intently stared at my bare, bruised stomach. “You must eat a lot of pasta.” The doctor smiled and pinched the fat on my stomach. I yelped out in pain and grabbed my swollen gut. Even when I had been sliced open, catheterized, and wrapped in an ugly blue gown, my fat was more visible than me or my scars.

I am not fat. I have scars on my stomach. I am often in pain. I am also a scientist, an artist, a painter and a sister. Yet, when people look at my bare body, they can only see one thing — flesh.

A version of this story appeared in the November 16 print issue.

Wellness Center Leaves Students Wanting More

Student well-being affects everyone in the NYU community, and the Wellness Center is an integral part of maintaining an undergraduate’s safety and happiness at their home away from home.

NYU’s Wellness Center has won some impressive accolades including the JedCampus seal for innovative mental health programs and with another location recently added to the Brooklyn campus, the university’s student health center seems exceptional.

However, individual students have given the center mixed reviews. CAS senior Jake* said his first experience at the Wellness Center was a drop-in visit, where he met with a counselor almost immediately and had positive results. Yet, he said his latest visit to the center ended poorly after not receiving any help from the staff.

“More recently I went to a drop-in visit again, but after waiting for about 40 minutes, I was told it would be another 15-minute wait, and so I left without meeting anyone,” he said. “I scheduled an appointment and I was given about a 12-day wait.”

Jake also expressed concern that the center is severely understaffed and lacking professional caregivers, and suggests this may impact the quality of counseling students receive. Washington Square News reported in a previous article that while 34 counselors work at the main campus location, only five are certified psychiatrists and only seven are certified psychologists.

CAS sophomore Noelle Kruse was required to meet with a therapist from the Wellness Center after medically withdrawing from classes last spring. Kruse said she felt like she was just a box to check off and said none of the staff members seemed interested in following up with her progress after her withdrawal.

“Throughout my spring and summer withdrawal, I got calls once in awhile from the Wellness Center to check on me, but they were usually a different person every time who didn’t know my case,” Kruse said. “The Wellness Center has been great for treating physical problems, but the mental health side could give their patients a little more attention.”

Several graduate students have also expressed concern about the Center’s quality of care. One graduate student in particular, Jane*, said one of her undergraduate students enlightened her to the state of mental health at NYU.

She said her student confided in her that the counseling she received at the Wellness Center was sub-par, and said the counselor she spoke with was patronizing and asked her to leave before the session was over. In addition, the undergraduate said as she was being guided through the conversation, as though she was hitting a brick wall with the counselor.

“My colleagues and I are always willing to talk to our students,” Jane said. “However, it can be burdensome because we’re not professionals, and we often worry the advice we are offering may not be the best. Someone needs to be there to listen, offer compassion and care about these students.”

Another graduate student, Carmen*, spoke of her personal experience using the 24-hour Wellness Exchange hotline several years ago.

“I had called one night because I was feeling a bit wound-up and thought talking to someone might help calm me down,” Carmen said. “The woman I spoke with was very rude and rather hostile. We had a short conversation, and I immediately called back to speak with someone in charge about my experience. However, I spoke with the same woman who became sarcastic and aggressive.”

Washington Square News was unable to reach a senior staff member at the Wellness Center for a comment, but according to their site, their “commitment is to treat patients with respect, compassion and sensitivity.”

*Names in this story were changed to maintain the confidentiality of those quotes.

A version of this story appeared in the Nov. 16 print issue. Email Lexi Faunce at [email protected].

An Industry Obsessed with the Body

In his controversial yet nonetheless relevant work, Sigmund Freud discussed the phenomenon of the fetish. The roots of the fetish lie in some original or organic object of desire from which feelings are displaced. In later years, Karl Marx related this theory back to the political economy with his explanation of the commodity fetish — the displacement of abstract values that elevate an object of economic desire into a subject of human relations.With the gradual expansion of its industry over time, fashion and its artistic properties have caused a shift in our own perception of dress, causing the very fabrics we live in to become their own living, fetishized subjects.

This path from object to subject has allowed for unfettered creativity and innovation for those who take pride in the sartorial. In response, however, the reverse process from subject to object can now be seen as a condition of the human body.

The objectification of the body is perpetuated perhaps no more by any other industry than that of the fashion industry. As satin and chiffon trail the catwalk displaying their own subjective qualities, the body ultimately becomes a secondary thing of economic value. This phenomenon is most obvious in the course of the model, and while we’ve begun to recognize the negative consequences of promoting one form of beauty, seemingly helpful reactions have continued this economics-centric gaze.

In April earlier this year, France became one of a handful of nations including Spain and Israel to pass Body Mass Index legislation. In hopes of regulating excessive thinness — which is defined as a BMI under — the bill passed by French parliament is no light matter. It enforces strict fines of up to 75,000 euros and a possible jail time of six months upon modeling agencies or fashion houses that are found using models below this accepted BMI.

The law came hand in hand with another bill passed by the country banning pro-ana websites. These social media pages on the rise actively promote an anorexic lifestyle with “thinspiration” photos, fasting challenges and online support from other anorexic individuals. While legislation like these two may seem beneficial in limiting the fashion industry’s tendency to body shame, they also work to reaffirm the fact that the body is now no longer a subjective being with abstract values. It is a commodified thing of desire that is manufactured as a product.

Even inclusive activity falls into this trap of treating the body as a profitable item. Calvin Klein’s inclusion of size 10 model Myla Dalbesio for their “Perfect Body” campaign was celebrated among many industry insiders. Plus-sized brand Lane Bryant’s #PlusIsEqual campaign brought to light yet another effort of promoting body positivity for all. Studies this year alone from the University of Kent and Brock University found that using more average-sized models in fashion ad campaigns would ultimately sell more clothes and be more marketable. While these efforts are surely commendable, they nevertheless center the body around its economic commodification — how sellable the body can be.

This is perhaps the crux of the fashion industry’s inability to promote an inclusive image of humanity — not all bodies sell. The waify models that strike a pose leave us wanting more from our own selves. In response, a turtleneck or flared jean becomes the subject then as they bestow expressive values upon the skin.

This phenomenon of the self as a secondary object to the subject of fashion is detrimental to the body. While legislation and ad campaigns may be promoted to deal with the problem of our own physical commodification, it will take more than a hashtag to reclaim the body as of equal subjectivity to that of a cerulean sweater.

A version of this story appeared in the Nov. 16 print issue.