How to Adjust Your Expectations

April 6, 2017

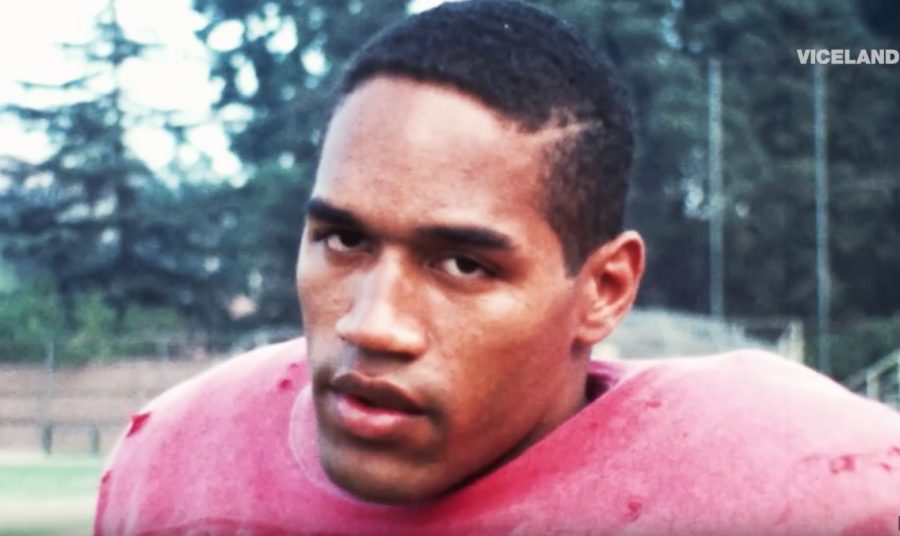

Documentary films are finally experiencing a revival of interest. The widespread popularity of Ava DuVernay’s “13th” and Ezra Edelman’s “O.J. Made in America” alongside the success of more unconventional documentaries like “Cameraperson” and “Life, Animated” in last year’s festival circuit demonstrate that non-fiction films can be as captivating as — if not more captivating than — fictional narratives. Perhaps it is due to the alarming rise of uncertainty in facts that permeates popular media that audiences seek a less fictional representation of their respective realities.

At the same time, the rigid distinction between documentary and fiction as opposing genres seems to persist in popular opinion — this division is more economic than structural. It’s hard to imagine producers and distributors successfully promoting a film as unclassifiable or somewhere in between — except among the tight avant-garde circles. But documentaries are not only for the enthusiasts of the weird, unobvious or non-didactic — addressing expectations of genre becomes important in the act of spectatorship. As documentaries increasingly engage all types of viewers, it seems relevant to ask once again what kind of filmmaking it is, or rather what it is not.

If fiction is an imaginative narrative and nonfiction is a series of evidential claims, then the latter appears more factually accurate. From this angle, we expect documentaries to be entirely non-fictional.

Yet nothing could be more misleading. In fact, the dichotomy between fiction and nonfiction predates documentary filmmaking by far — it can be traced as far back as 1855 when during the Crimean War, Roger Fenton shot two photographs of The Valley of the Shadow of Death. The photograph Fenton exhibited to the public showed cannon balls scattered across a road, but another photo on his reel depicted the road partly cleared. Debate blew up over which photo was taken first and if Fenton altered the landscape, begging the question of whether his photograph was historically valid.

The most intriguing answers support Fenton’s possible alteration, arguing that by doing so, he gave a more forceful depiction of the ongoing war — without detracting from factual accuracy.

Centuries later, documentaries still tread this delicate path but are disputed with even greater impact. In “The Thin Blue Line,” filmmaker Errol Morris famously showed that imaginative re-enactments can service truth more than a purely observational approach. Morris’ investigation into the shooting of a Dallas police officer involved milkshakes flying in slow motion and interviews with bizarre non-participants, yet it still proved the main suspect innocent, counter to the prosecutor’s ill-researched verdict.

The social and political consequences of re-enactments are similarly made evident in Joshua Oppenheimer’s “The Act of Killing,” in which two perpetrators of mass executions in Indonesia took pride in rehearsing and staging glamorous versions of their crimes. Oppenheimer’s perversely lush account of history gives the only proper insight into the corrupting appeal of brutality and fame that motivated the killings. By acknowledging the real-world impact of these two films, we can see that documentaries need not rely on objective evidence — they can tell true stories through cleverly-constructed narratives and various emotive techniques.

The most accurate distinction between fiction and documentary narratives lies then in the latter’s quest for truth. Errol Morris commented on “the verite in cinema” in an article for The Boston Globe.

“No art form can give us truth on a silver platter,” Morris said. “But [documentary] can present evidence in such a way that we can think about what is true and what is false.”

Here truth becomes both a quest and a broad category — something to pursue and seek out. At the same time, truth itself is a broad category. A filmmaker can strive for emotional truth, factual truth or epistemic origins of a given subject. This is why employing fiction is not simply a dramatic strategy. The overlap between drama and testimony allows us to better understand our relationship to truth and reality, as it is always filtered and skewed through subjective perspectives.

What’s exciting about current documentaries is that they celebrate an ever more creative approach to truth-seeking. For example, “Actor Martinez” and last year’s “Kate Plays Christine” look at identity creation by having actors play themselves, while also attempting to perform a role. Raoul Peck’s widely acclaimed “I’m Not Your Negro” mixes an overwhelming amount of pop culture and historical footage, past and present, to transpose James Baldwin’s reality of the 1960s onto today.

Counter to conventional wisdom, such hybridity should feel natural. After all, fiction is an integral part of our daily lives. In the era of ubiquitous social media, we are constantly creating our own narratives and fashioning our identities. This doesn’t always have to detract from our sense of truth — the selectivity and the performance are in themselves signifiers of how we understand facts.

Yet the attitude toward genre tends to be less imaginative. Documentary still connotes facticity. Given that we satisfy our own needs for a particular lens or filter on a daily basis, why are we surprised when a filmmaker toys with narrative in documentary to transport us into someone else’s reality? On one hand, we’re no longer allowed to suspend disbelief as we would do in “Christine,” the film account of real-life journalist Christine Chubbuck. On the other, we have to reject the naive notion that what happens onscreen in “Kate Plays Christine” is what in fact happened on set. The truth is found somewhere in between.

If our expectations are at least in part what determine genre, then by easing the insistence on didactic form we can widen the space for hybrid filmmaking. Filmmaking that has a better chance of addressing the nature of facts and the ethics of storytelling — an especially pertinent quest now that alternative facts and the aesthetics of reality television seep into our politics.

So whether you’re watching the straightforward “13th,” or the unsettlingly entertaining “Making a Murderer,” keep in mind the filmmaker’s freedom to bridge and overlap material. Done well, it will not result in a blurring of facts but in a merging of worlds — past and present, local and global, private and public.

A version of this article appeared in the Thursday, April 6 print edition.

Email Zuzia Czemier-Wolonciej at [email protected].