The Arts Issue: Majors vs. Indie

September 29, 2016

During my very first semester at NYU, my Writing the Essay professor, while talking about Damien Hirst’s piece “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” (which, for those yet to take the course, is simply a taxidermied tiger shark floating in a vitrine of formaldehyde), casually said what has sat with me ever since as one of the most important things to remember about art in our modern era: “Art now lies in the concept, not the execution.” He was referring to the way that all of the weight of Hirst’s piece was not in the relatively unimpressive setup of a dead shark in a tank, but in the things the shark made viewers think. Just like Marcel Duchamp’s famed 1917 piece “Fountain” (a urinal set on a stool, signed brashly with the artist’s pseudonym “R.Mutt”), it was not the art, but the reaction, that drove the artist to create.

Three years and a lot of mused-over cups of coffee later, I’ve decided that the principle of finding the significance of art in its concept is not only limited to sculptures that we otherwise would dismiss as lazily provocative or, even more boldly, not art, but is important to consider in the context of all art. The context of a piece’s conceptual significance is crucial for understanding an artist’s purpose and the art’s place in the larger fabric of culture. It is what differentiates art-for-thinking from art-for-entertainment; it is what allows Katy Perry to exist and be considered a musician and an artist alongside her peers like Father John Misty and Yo-Yo Ma.

I wanted to make this theme focus on one of the most determining factors in a piece’s conception, creation and reception: the budget and resources available to it by sheer virtue of who is involved in making the work. The way that an artist’s budget affects their art can often be clearly seen. The effects of its thus-determined genre, however, are harder to discern. What happens when a major music record label releases a CD through the independent record label that it owns? Is a musician still indie if they sound like The Decemberists but are signed to a label?

Past classification, once we pin down what’s indie, how does this influence the way we think about the artwork or listen to the music or watch the movie? What awards is it eligible for? Who gets the credit for work well done? What situations are best to engage with that art? The truth is, calling something “major” or “indie” affects a lot more than the project’s budget. There are biases built up around every label we can put on art. There are privileges given to certain categories and not others, and comparisons and contrasts are made according to those categories.

This issue holds a lot of opinions, facts and stories. It holds a lot of hard work. Mostly, it holds a lot of art. I encourage you, the reader, to read it and consider what it means — what it all means. Not just whether low-budget films are better or whether modern visual art is just a lot of nihilists addicted to cheap cigarettes, but whether you’re putting weight in the execution or the concept. What it means to publish your own book. Whether “high art” is a compliment. Whether “indie” is a genre. Whether it matters.

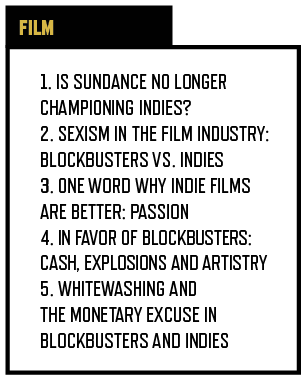

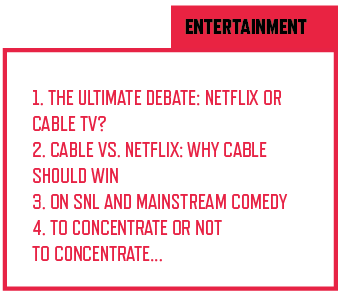

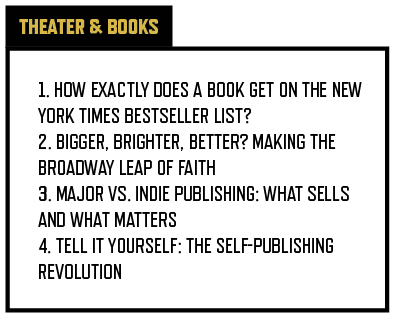

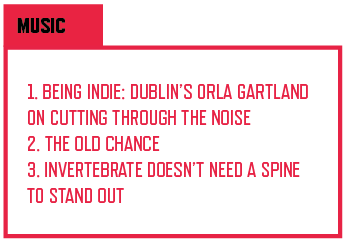

Click on a section to be taken to those stories.