Personal Essay: Flesh

November 16, 2015

Five, 10 and 21 — the number of surgeries I’ve had, scars left on my body and inches of intestine removed. Last summer during my Intro to Photography class, I took photos of the pink scars lining my torso. I was not thinking about body image. In fact, I barely think about it. When you have a chronic illness like Crohn’s Disease, your weight and health fluctuate so much and so rapidly that you rarely have time to worry about your appearance. Yet when I presented my photos to the class, the professor didn’t seem to notice the scars.

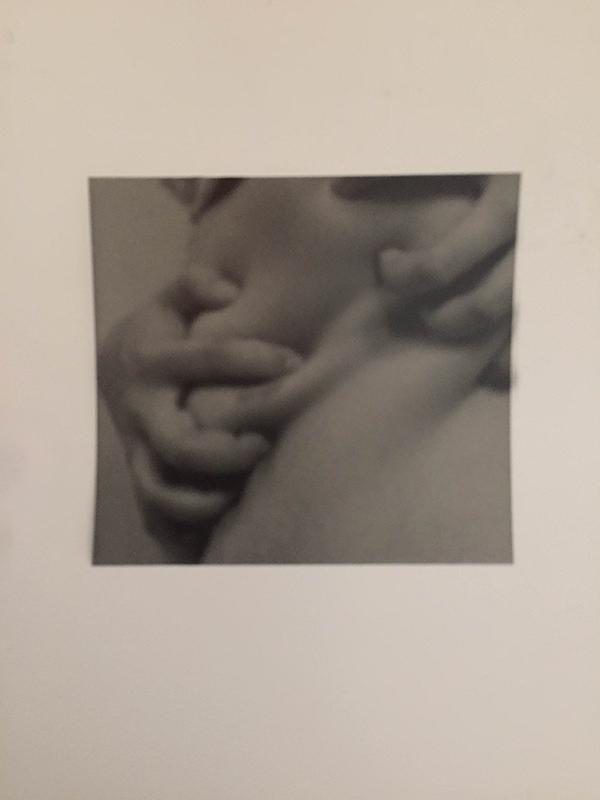

The photos were zoomed-in shots of my body. I had set the self-timer on the camera so that I could use both my hands to grab my flesh to look like I was trying to rip my body open, just like all of the surgeons that have sliced my flesh since I was three years old. In the developing lab, I spent over an hour re-adjusting the contrast so that my scars were distinct from the rest of my skin. My goal was to show a side of me that is otherwise invisible. I am not skinny or fit, and while I’m a bit pale, I don’t really look sick. This was my chance to reveal something I had kept hidden for so long, and here I was — about to share it with a group of people I had only known for a few weeks.

After pinning up my photos next to my classmates’ work, I nervously awaited my professor’s critique. Did I use too much contrast? Was there not enough versatility? I went down the checklist of everything that I could have done wrong, when the teacher finally arrived at my piece. I perked up and leaned forward to hear what he had to say. “Ah, I see. Yes, I get it,” he remarked, “We’ve all got a little pudge on us.”

I immediately sank back in my chair. There was nothing that could have prepared me for that response. All I could do was nod my head and twiddle my thumbs. In my life, a lot had been done to evaluate my body — CT scans, MRIs, colonoscopies, ultrasounds and biopsies. Yet, here my body was being evaluated by a non-medical professional, in a way that would never possibly help me lead a healthier, better life. My scars are not large, but they are certainly not imperceptible.

The professor’s comments left me feeling confused and insulted. I couldn’t quite grasp why the soft flesh on my body mattered–having fat on my body meant that I was relatively healthy, but it became now it seemed that my fat was worse than my scars. On my walk home from class, I was reminded of a doctor who once examined my freshly post-surgical torso. She and a team of medical interns intently stared at my bare, bruised stomach. “You must eat a lot of pasta.” The doctor smiled and pinched the fat on my stomach. I yelped out in pain and grabbed my swollen gut. Even when I had been sliced open, catheterized, and wrapped in an ugly blue gown, my fat was more visible than me or my scars.

I am not fat. I have scars on my stomach. I am often in pain. I am also a scientist, an artist, a painter and a sister. Yet, when people look at my bare body, they can only see one thing — flesh.

A version of this story appeared in the November 16 print issue.