Rape through the lens of a survivor

University suspends student guilty of rape

December 4, 2014

Trigger warning: rape, sexual assault, suicide, self-harm, PTSD

Ashley Sweeney looked down at her hands for a couple of seconds before looking back up.

“You know, everyone is a completely new person every few years. All the cells in your body are different,” she said. “I feel like it happened so much faster for me. I am completely unrecognizable from the person I was on Sept. 12 of last year.”

Sept. 12, 2013, was shortly after Sweeney arrived at the then-Polytechnic Institute of NYU, now-NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering, from Missouri. She quickly made friends with fellow freshmen during the university’s Welcome Week, including then-freshman Brandon Olsen. Sweeney said Olsen was funny and likeable, and it did not take long for them to get close. Within a week, they had kissed.

“A day later, he asked me out,” Sweeney said.

She turned him down. Though she liked him, having just moved away and started college she did not feel ready for a relationship.

On Sept. 13, the two, along with other friends, traveled to a mutual friend’s house in Neptune City, New Jersey. After having a few drinks, they chatted outside the house. Olsen again brought up his desire for a relationship. Sweeney said she felt uncomfortable with his persistence. Rebuffing his advances, she wandered through the house, eventually ending up in the basement. Olsen followed her there. They kissed, and Olsen started taking off her clothes.

Initially, she was passive. But as his intentions became clear, she resisted. As he pulled her on top of him, she told him to stop and tried to pull away. He did not budge, deaf to her pleas.

“His eyes had glazed over,” she remembered.

As Sweeney struggled to free herself, a friend came downstairs and witnessed the assault in progress. Sweeney called out to him, asking him to intervene, but he turned around and headed back up the stairs.

After it was over, Sweeney got dressed and made her way upstairs to the others. She broke down, sobbing. For the rest of the night, her friends kept Olsen away from her as she tried to sleep.

Five months later, Sweeney found herself reliving this night. With the help of a friend, she had filed an incident report with NYU. An investigation ensued into the allegations, which culminated in a University Judicial Panel hearing held on March 25, 2014.

The four-member judiciary panel weighed the evidence, which included Facebook messages between Olsen and Sweeney in which Olsen admitted to raping her.

“I have no idea what possibly possessed me to rape you. Whether I meant/wanted to or not, I did,” his Facebook message read.

For the allegation that Olsen had “engaged in non-consensual sexual intercourse with her in an off-campus location by ignoring her requests and efforts to get him to stop,” the panel found him responsible.

Olsen was suspended for the remainder of the spring semester, effective April 6, 2014, and the entirety of the fall 2014 semester, and was banned from housing.

According to the hearing’s decision, Olsen is eligible to return to NYU as a student in the spring 2015 semester, provided he undergoes counseling to “address whatever issues may have contributed to, or precipitated, his behavioral choices,” performs community service and does not communicate with Sweeney.

No notation of the disciplinary action was placed on his university transcript. He lost all credits for which he was eligible in the spring 2014 semester.

Olsen declined to comment through his lawyer and did not confirm whether or not he is returning.

Staying Afloat

For two months after the rape, Sweeney tried to carry on normally, focusing on her classes and starting therapy sessions at the NYU Wellness Center. She still saw Olsen on campus. Before his admission of guilt over Facebook, Olsen maintained that it had not been rape and that they should date. One day, feeling defeated, she agreed to date him.

“I thought about just trying to kill myself that night. Living to the next day, I eventually told Brandon that the only reason I agreed to dating was because I didn’t really care to live any longer, the idea that I had invented the thing that had been tormenting me for a month being too much to bear,” she wrote in the report.

Apart from the friends that were present at the house in New Jersey, she confided only in her family and her therapist about what had happened to her.

As the semester was drawing to a close in late November 2013, Sweeney reached a breaking point. She was in her room at Othmer residence hall. She had fought with Olsen, who had told her to stop bringing up the assault and telling others about it. He stormed off, only to return and insist that she sleep at his dorm. Feeling trapped, she agreed. She told him to go ahead to bed, that she would be right there. Then, she went into the bathroom and sliced her neck open.

“I slit my throat because I didn’t think I could get away from him and be alive,” she said.

Sweeney was hospitalized twice following the incident — once to stitch up her neck, and then again for university-mandated psychiatric evaluation.

After being released from the hospital, Sweeney attempted again to carry on normally.

Two months later, on Feb. 1, 2014, another encounter with Olsen led to her filing the report. She had allowed him to sleep on the couch in her dorm room after he was locked out of his own room, but awoke to find him in bed with her.

After filing the report, per protocol, university officials informed her she could file police charges with university help.

Though she initially declined, a few days later she told her friends that she planned to go to the police. They discouraged her, especially the friend at whose house the assault took place. Sweeney said she was appalled — her friends had turned on her. After that, she drank alcohol and swallowed pills. Olsen’s suitemate found her and forced her to throw up the pills.

“Afterward, I never heard from any of them again,” she said, referring to her friends.

The next morning, Sweeney visited the hospital. When she returned to her dorm, she was informed that she would not be allowed back in. She said she had been called a hazard to fellow students and was told to return to the hospital for an evaluation. She was then placed on medical leave for the remainder of the semester.

She independently filed charges with New York and New Jersey police in mid-February.

Neither of the police reports filed have resulted in a trial as of press time.

“Shedding the Shame”

The Hearing

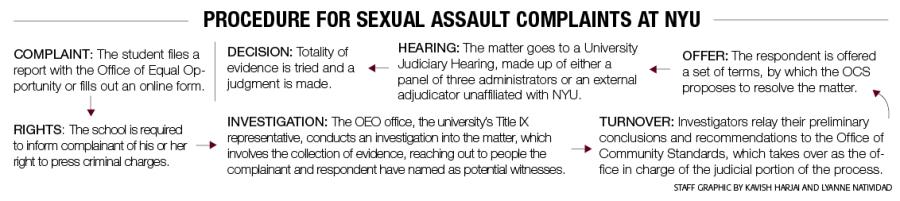

By the time a case reaches the University Judicial Panel, it has already gone through two NYU offices. The first step in the process is when a survivor, or “complainant,” registers a complaint with the university. This can be done in multiple ways, such as walking into the office of Mary Signor, executive director of NYU’s Office of Equal Opportunity and Title IX representative, or filling out an online form requesting a callback.

“That student will be contacted within 48 hours by our office,” Signor said. “It’s usually a lot sooner, I’d like to say probably within three hours, when I receive it.”

If the complainant names a perpetrator, or “respondent,” and decides to proceed with the investigation, the OEO will contact the respondent.

After the outreach, the OEO conducts an investigation. The investigators collect evidence and, at their discretion, reach out to the people that the complainant and respondent have named as potential witnesses.

Sweeney named five witnesses, all of whom were present at the time of either the initial assault or subsequent harassment. She does not know how many of these were contacted by university investigators.

Four refused to comment and one did not respond to WSN requests.

After the investigation is completed, the investigators relay their preliminary conclusions and recommendations to the Office of Community Standards, which takes over as the office in charge of the judicial portion of the process.

NYU director of Community Standards and Compliance Thomas Grace said after the investigation, the office meets with the accused student.

“We sit with that person, and based on past practices in the university, based on what we believe we’ve learned happened, that person is offered a set of terms, by which the university proposes to resolve it,” Grace said.

If the accused does not accept any of these terms, the matter goes to a University Judiciary Hearing. Olsen rejected the terms Grace offered him and the matter went to the hearing.

Sweeney was not physically present at the University Judicial Panel hearing on March 25 due to her medical leave, but was present over the phone. Sweeney did not have a lawyer.

“I just had myself, and that was probably something that maybe was part of why it was so unpleasant,” she said. “They told me that I could have a lawyer present, but we couldn’t really afford to be paying a lawyer for that whole business.”

Olsen was present, and had hired a criminal defense lawyer.

The panel that heard the case comprised the dean’s representative Sherry Glied, Faculty Senate representative Achiau Ludomirsky, Student Senate representative Kevin Jones and Administrative Management Council representative Levon West. Citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, Glied, Jones and West declined to comment. Ludomirsky did not respond to requests for comment.

WSN also did not have access to all the details of the hearing because of Olsen’s FERPA rights.

Grace said a member selected by each of these four groups was the standard structure for a university judicial panel up until the restructuring specified in the university’s newest sexual assault policy, which went into effect on Oct. 1, 2014.

Now, a panel is made up of three members, taken from a pool of administrators and faculty members that have been vetted by the university. If the OCS decides that there is a specific conflict of interest that would not allow for a panel to make a fair decision, an external adjudicator, who is not affiliated with the university, hears the case.

William Miller, a member of the NYU General Counsel’s office who participated in the drafting of the new policy, explained the decision to exclude students from serving in judiciary panels.

“There are various guidelines from the federal government that are issued by the Department of Education, and within that, recently, in April of this year, they issued guidelines which specifically said they strongly discourage schools from having students on the panels,” Miller said.

Meghan Racklin, a junior and the president of the NYU Feminist Society and treasurer of Students for Sexual Respect, was in disbelief when she was informed of the one-semester suspension.

“In light of the fact that research says that the overwhelming majority of campus rapes are perpetrated by repeat offenders, that verdict is not only unfair to the survivor, but irresponsible and dangerous for the community at large,” Racklin said. “The notion that a panel of people who are responsible for the well-being of the campus community would let this person back on campus is ridiculous.”

Under school policy, Olsen was found guilty of non-consensual sexual intercourse, but he was found not responsible for the allegations of harassment and intrusion into Sweeney’s bed.

Case by Case

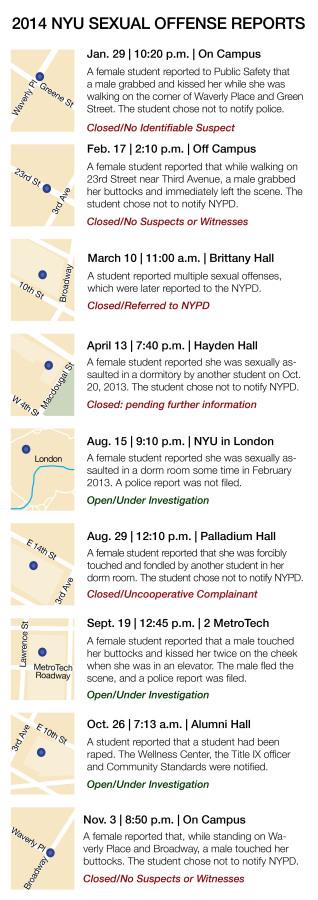

Information via NYU Crime Reports and Statistic

The University Judicial Panel has total discretion in deciding on a sanction in the event that a respondent is found responsible for violating university policy. In the case of Olsen, the panel suspended him — in other cases, respondents could be expelled for the same violation.

“We did look back at the last three years’ worth of disciplinary outcomes involving violations of our sexual misconduct policy that seem roughly akin to this case,” NYU spokesman John Beckman said in an email. “We found that suspension and expulsion were equally common outcomes when sexual misconduct was found to have occurred, applied in accordance with the unique circumstances of each incident as supported by the evidence.”

Beckman said the panel did not have any guidelines in determining sanctions.

“In the end, the panelists look at the totality of the evidence and try and make a judgement based on that,” he said.

“The university does not have a specific, like, ‘If you’re found responsible for this, this is the sanction,’” Grace added.

Miller said the guidance that a panel has in selecting a suitable punishment are a set of factors outlined in the policy, which include “whether [the conduct] involved violence” and “whether the respondent has accepted responsibility for the conduct.”

The university did not provide statistics on the number of sexual misconduct reports leading to hearings in any year, or how many students have been found responsible for policy violations of a sexual nature, citing FERPA.

“The criminal justice system is a far more transparent system than the disciplinary system in colleges and universities,” Beckman said. “That’s not particularly because the colleges or universities have asked that it be closed, but because of these privacy laws.”

Racklin said the lack of transparency is worrisome.

“We find it problematic that the panel is made up of administrators and deans. There’s a huge conflict of interest there,” she said. “They have far too much incentive to not make this a transparent process.”

Looking Forward

Despite all circumstances, Sweeney remains determined to be part of the national movement toward a fairer handling of sexual assault.

“There’s a list of universities that are under investigation for their handling of sexual assault,” she said. “The list does not cover anywhere near the schools that handle it poorly, because nobody wants a scandal. This is an issue that everyone should be talking about.”

If given the option to reopen the case — though under current NYU policy, cases cannot be reopened — Sweeney said she would not.

“I wouldn’t reopen the case, probably specifically because NYU didn’t kick him out,” she said. “I think that it should be known that NYU found him guilty of rape and only kicked him out for a semester, because I don’t want to offer them the chance to fix the mistake that they made.”

A version of this article appeared in the Thursday, Dec. 4 print edition. Additional reporting by Emily Bell, Nicole Brown and Dana Reszutek. Email Felipe De La Hoz at [email protected].

Resources

Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network

National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-HOPE

NYU Langone Medical Center

Institute for Trauma & Stress

215 Lexington Ave., 16th Floor

(212) 263-2481

Beth Israel Center

Rape Crisis & Domestic Violence Intervention

317 E. 17th St., Fourth Floor

(212) 420-4516

Bellevue Hospital Center

Rape Crisis & Advocacy Program

462 First Ave.

(212) 562-3435

Mount Sinai Medical Center

Adolescent Victims Program

312 E. 94th St., First and Second Floors

(212) 423-2900

National Context

SUNY Announces New Sexual Assault Policy

SUNY unveiled a new system-wide sexual assault policy on Dec. 2, following Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s call for a comprehensive and uniform policy on all campuses. Universities within the SUNY system will have until March 31 to present a plan explaining how they will ensure compliance with the new policy.

The policy will include a Sexual Violence Survivor Bill of Rights, which clearly outlines the rights survivors are entitled to when reporting a sexual assault, as well as the options and support the university provides. Schools including NYU, The New School and Columbia University do not present the rights of survivors in this manner. The policy also includes an 11-line affirmative consent definition, and provides amnesty for survivors who used drugs or had been drinking at the time of the assault.

What is the Federal Sexual Assault Policy Mandate?

President Barack Obama signed the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act in March, which requires colleges to update their sexual assault policies by clarifying their reporting policies, and providing educational programs to students and personnel. The new requirements are outlined under Section 304 of the Campus Sexual Violence Act provision. Under the act, colleges have to provide annual statistics of domestic violence, dating violence and stalking. Schools are required to inform students about where they can receive help and report abusive behavior. School policy must also protect the confidentiality of the victim’s identity. Colleges are required to educate students and personnel on the definition of abusive behavior and consent, and provide a statement explaining that abusive behavior is not allowed. The mandate required that these changes be made by Oct. 1.

What Does Title IX Mean?

Title IX is a section of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prevents discrimination based on gender in educational institutions.The law also allows the Department of Education to investigate schools for including sexual assault, harassment and violence, which are considered a violation of a student’s civil right to education as they create “a sexually hostile environment.” There are currently 86 schools in the United States under Title IX investigation. While the majority of those schools are being investigated for specific complaints of sexual discrimination, 13 of them are under “compliance review,” which allows the DOE’s Office of Civil Rights to identify and remedy cases of sex discrimination, which may not be addressed through complaint investigation.

Email the news team at [email protected].